2050: It's sooner than you think [NGW Magazine]

There is not much time to work out a coherent European energy strategy centred on gas, as the amount of work to be done at a political, technical and commercial level is colossal. And some key elements of a low-carbon future, notably large-scale carbon capture and storage, are still on the drawing-board — if that.

Energy infrastructure consultant Sean Waring says there is therefore the risk that the economic benefits of a decarbonised gas system could be swept aside as the climate agenda moves quickly and gas is left behind by countries or regions who decide to pursue all-electric options for political or practical reasons, with possibly adverse consequences for their neighbours downstream of the gas supply.

Addressing this problem is a matter of urgency and should be a priority for the new European Commission as a clear co-ordinated energy and environmental strategy is needed. There needs to be some degree of leadership; work needs to start on devising an energy supply industry, one that will fit with the 2040-50 objectives, the former Interconnector UK boss told NGW in an interview early July.

“Decarbonised networks need bigger electricity systems — maybe three times bigger to — fully replace gas as the main source of heat. We have the high-level political declarations like in the UK, and a lot of the EU would go along with the UK aim to go net-carbon neutral by 2050,” he said.

The consequences of failing to put a strategy in place could be dramatic. Suppose one country, for example a transit country, decides to go all electric: what does that mean for pipe-line supplies across those countries? How will those policies impact countries downstream? “It seems that we are at a very early stage of what needs to be done, and a new policy and regulatory structure is needed,” he said.

The current structure of the industry, most recently implemented through the third energy package, introduced the liberalised, market based system driving choice and lower prices for consumers. There is a question whether this structure can address the scale of the change required to meet the 2050 climate goals. The scale of change can be so large that a more co-ordinated, systematic approach to manage decarbonisation and shrinking gas demand could be needed, he says.

Politicians and regulators need to engage with the industry quickly to develop the necessary frameworks to deliver the benefits for society in terms of economic, low-carbon and secure energy supplies. Energy remains a highly political issue and with decarbonisation rapidly increasing in the public consciousness, this could become an election issue, with political rivals bringing forward more ambitious zero carbon plans without a fully developed understanding of the options available or the costs. And the population is likely to approve the most ambitious goals, even if the costs of doing so are unknown.

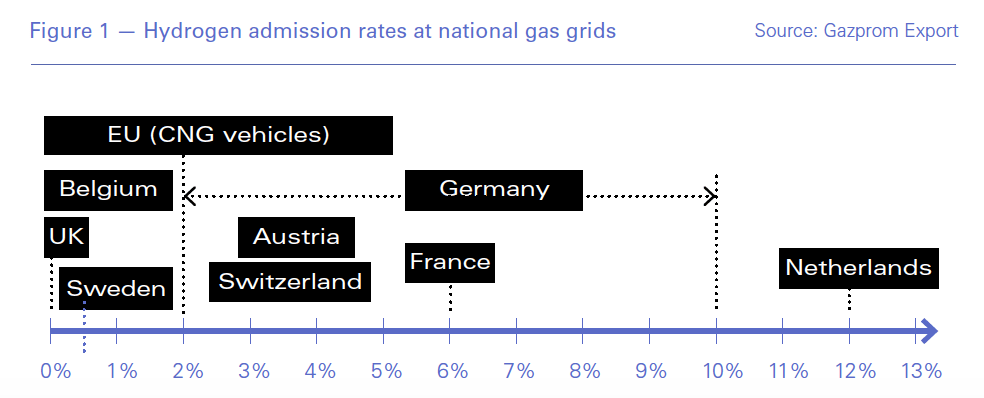

Hydrogen is seen as the best route to decarbonise the gas industry and deliver the lowest cost solution to society but without a common policy, it is likely that countries, regions and even individual cities will pursue separate paths in terms of technical solutions with differing policy frameworks. There are many different ways of reaching grid-ready hydrogen; some start with natural gas, and others with water of even solid waste. They all have different by-products, costs and technologies. This divergence could make cross-border flows difficult to negotiate. A lot of hydrogen will be locally produced: some in countries where steam methane reformation and carbon capture and storage are the way to proceed; others using electrolysis, he points out.

Coal has been the villain of the piece from an environmental point of view, but with coal going, the popular attention will switch to gas. The climate agenda has clearly moved on rap-idly in the last few years and even the last few months and people are expecting a solution. While the gas industry is making real progress on the development of hydrogen as a solution, this still has to be sold to the policy-makers and the wider population. There will have to be huge investments and interruption at all levels with adjustments to domestic appliances — a major task, as evidenced by the very slow progress made with the relatively simple job of installing smart meters in the UK.

Although a fully electric option will be a lot costlier than repurposing the gas network, that too will have a cost for the economy. Transmission and distribution system operators can take a technical lead and make proposals and lay out options, but they have traditionally not been the kind of organisations that can risk billions on a project, in today’s regulatory structure. The gas industry therefore has to work with governments and regulators on how to co-ordinate, deliver and pay for the transition, as big money is needed to transform the industry. The people who built the gas industry were national champions backed by governments but now the upstream and the gas marketing arms are separated from the networks businesses. While this has benefited competition, ending cross-subsidies and allowing customer choice, the fact remains that those new businesses, the transmission system operators, have different economics and risk profiles. Network companies are stranded by geography with assets in the ground, while producers have a world market to supply.