A disappointing year for Senegal’s nascent gas sector [Gas in Transition]

Senegal entered 2023 with the expectation that it was on the verge of entering the ranks of the world’s natural gas producers. At the time, it had good reason to believe it was just a few months away from achieving this milestone.

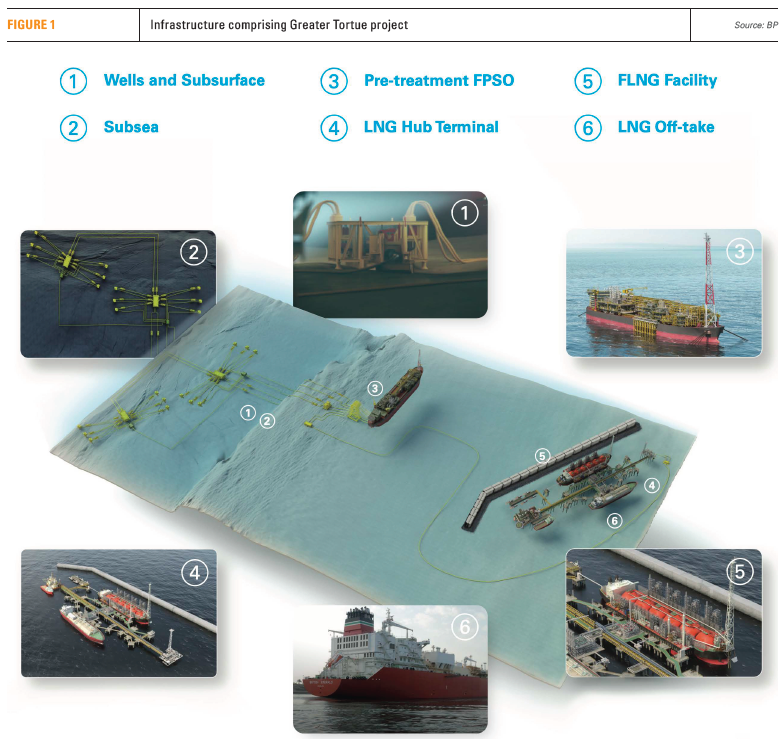

First and foremost, it was close to beginning production at Greater Tortue/Ahmeyim (GTA), an offshore block shared with neighbouring Mauritania. As of the beginning of 2023, UK-based BP and its US partner Kosmos Energy were anticipating bringing the block on line before the end of the year. They had nearly all of the equipment they needed in place to start production in the third quarter and then launch a floating LNG (FLNG) unit in the fourth quarter, in time to send their first shipment of LNG to Europe before the end of 2023.

Secondly, GTA wasn’t the only project in the pipeline. BP and Kosmos were also laying a foundation for launching their next project offshore Senegal: Yakaar-Teranga, which targeted another block further north in the same basin. As of early 2023, the two companies were optimistic that they might be able to bring this site on stream some time in 2024.

It’s now late 2023, though, and neither of those objectives has any chance at all of being met on time.

On the one hand, BP has pushed the start date for gas extraction and LNG production at GTA back into 2024. On the other hand, the UK-based multinational has decided to withdraw entirely from Yakaar-Teranga and is leaving the project entirely in the hands of its erstwhile partner Kosmos Energy.

So what has changed since the beginning of the year?

Costs and delays at GTA

One of the factors upending the production schedule has been cost – specifically, the cost of converting a former tanker into the FLNG unit that will be installed at GTA.

BP had tasked Bermuda-registered Golar LNG with carrying out the tanker conversion under a 20-year charter agreement signed in 2019. At that time, the parties estimated the cost of that job at $1.3bn. Later, however, Golar LNG fell into a dispute with BP over the interpretation of contract provisions concerning cash flows prior to the vessel’s commissioning.

As a result of these setbacks, the FLNG vessel did not depart from Singapore until mid-November. Even so, BP’s interim CEO Murray Auchincloss struck a hopeful note in his company’s second-quarter report, saying that he was hopeful of seeing GTA start production in the first quarter of 2024. But Kosmos was less optimistic, saying that there might be more delays to come.

BP’s US partner was basing its prediction on the fact that the FLNG is not the only facility to be delayed. In its third-quarter report, Kosmos pointed out that the floating production, storage and off-loading (FPSO) vessel slated for installation at GTA was also running late, meaning that the subsea workstream had fallen off schedule. BP then confirmed in its own third-quarter report that the FPSO was still in transit and had yet to arrive at the block, but Auchincloss also insisted that he still expected gas production to start in the first quarter of the new year.

Regardless of which party is correct, however, it is clear that BP and Kosmos have failed to achieve their aim of launching gas production at GTA this year.

In other words, Senegal is still waiting to launch its first gas project.

Uncertainty over Yakaar-Teranga

Meanwhile, its second gas project is also facing serious challenges. It became clear last month that BP and Kosmos are unlikely to bring Yakaar-Teranga on stream in 2024 as they had predicted earlier.

The reason for this shift is that BP, the operator, announced in early November that it was withdrawing from the project. The British super-major did not offer any detailed explanations for its decision, saying only that it had determined that the scheme was no longer in line with its strategic objectives.

Kosmos, meanwhile, confirmed BP’s departure and said it was now set to raise its holdings in Yakaar-Teranga from 30% to 90% and assume the operatorship, even though Petrosen, the national oil company (NOC), was likely to increase its own stake from 10%. (Senegal’s Minister of Oil and Energy Antoine Félix Diome also confirmed these developments and added in late November that BP had actually exited the project without seeking any financial compensation for its forfeited stake.)

Kosmos, meanwhile, confirmed BP’s departure and said it was now set to raise its holdings in Yakaar-Teranga from 30% to 90% and assume the operatorship, even though Petrosen, the national oil company (NOC), was likely to increase its own stake from 10%. (Senegal’s Minister of Oil and Energy Antoine Félix Diome also confirmed these developments and added in late November that BP had actually exited the project without seeking any financial compensation for its forfeited stake.)

Although BP has not commented directly on the matter, a number of other sources have suggested that the multi-national quit the project because of disagreements with Senegalese authorities over how best to allot future gas production from Yakaar-Teranga. Officials in Dakar were reportedly pushing BP to send nearly all of the block’s output to shore for local consumption, while the British major would have preferred to reduce the amount available to Senegal and increase LNG exports in order to maximise its revenues.

With BP out of the running, Kosmos now seems to be trying to strike a balance. The US company said in a statement on November 6 that it wanted to work with Petrosen to prioritise deliveries of gas from Yakaar-Teranga to the domestic market while also installing an FLNG vessel at the block to enable exports.

Senegal’s hopes

It now remains to be seen whether Kosmos can actually strike that balance.

This is a tall order, given the lofty combination of financial, environmental and socioeconomic goals identified by the company’s chairman and CEO Andrew Inglis in a statement dated November 6: “Yakaar-Teranga is one of the crown jewels of Senegal’s growing energy sector and this aligned partnership allows Kosmos and Petrosen to accelerate the development of a cost-competitive gas project supporting Senegal’s goal of providing universal and reliable access to low-cost energy. The project is also expected to lower emissions by displacing heavy fuel oil in the country’s energy mix. In addition, the project is expected to deliver LNG export volumes to global markets, further establishing Senegal as an important and reliable supplier of energy to the world.”

It is also a tall order in light of the fact that the development scheme has yet to be finalised. Kosmos made note of this in its statement last month, noting that it had not even begun front-end engineering and design (FEED) work on the offshore facilities that will handle production from the offshore block.

Of course, this is not an insurmountable hurdle. The US company can certainly secure FEED services for an offshore complex that includes production facilities, an FLNG unit and pipelines capable of pumping gas to shore if it can raise the money and find a contractor.

However, these processes will take time – several years, in all likelihood – and Senegal had rather hoped, at the beginning of 2023, that it would not have to wait much longer for the gas to start flowing. As such, this year has been a disappointing one for the country’s nascent gas and LNG industry.