A year of two halves? [NGW Magazine]

The warmest winter on record was tough for Gazprom. Year-on year revenue dynamic for January 2020 marked a loss of 41% compared with January 2019, and the company chose not to take advantage of low prices to extend market share.

The Covid-19 pandemic, hot on the heels of a very warm winter that left a lot of gas in store, hit Gazprom’s sales. By mid-2020 Russian sources reported a 20% decline of gas exports during the first six months of 2020 compared with the same period of 2019.

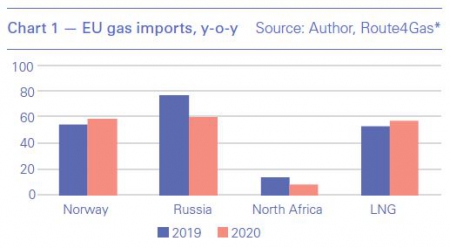

Data on year-on-year imports to the EU confirm a sharp decline of Russian pipeline exports compared with the previous year (Chart 1).

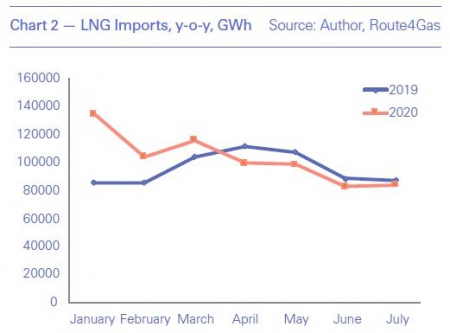

Despite a difficult start in terms of volume and price, Gazprom recently announced a revised exports forecast of 175bn m³. This small increase was based on the strong surge in August sales and suggests Gazprom hopes to take advantage of the continuous cancellations of LNG cargo shipments to Europe that has been a feature of the market since the Covid outbreak and pushed exports lower than last year. US exports fell by some 40% this summer which certainly tightened supplies to Europe as well. As a result, record-high LNG inflows in early 2020 faced a correction and LNG imports decreased (Chart 2).

This downward trend in LNG supplies rather benefits piped gas imports. For instance, Chart 1 also illustrates an increase of Norwegian natural gas volumes by some 6%. A decline of Russian flows in contrast to the Norwegian supplies growth is rather short term as it can be partly explained by maintenance work on Nord Stream during this summer. Hence, recovery of Nord stream deliveries and developments in LNG may give Gazprom a hypothetical opportunity to regain market, but under hypothesis of faster demand recovery and a colder fall and winter than in 2019.

While Gazprom’s bet on market expansion remains anyone’s guess, another Russian supplier, Novatek, has already taken advantage of the decline of US LNG inflows. Exports from Yamal rose by 5.9% year-on-year, and by 36% from Cryogas Vysotsk which started in April 2019.

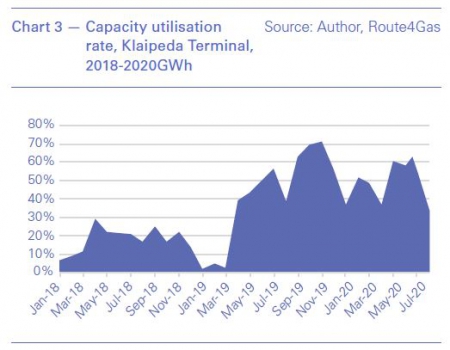

The latter is in a particularly advantageous position on the Baltic coast and has significantly increased its presence in Lithuania’s Klaipeda LNG terminal. Chart 3 shows that since the access rules at the Klaipeda terminal changed in March 2019, Klaipeda LNG utilisation rate has risen. By June 2020, Norway had supplied up to 70% of Klaipeda capacity, while US and Russian suppliers competed almost neck-and-neck with 18% and 12% respectively. Cryogas-Vysotsk will most probably increase its share of the capacity at the terminal, which has been called – now seemingly ironically – Independence to mark Lithuania’s termination of dependence on Gazprom. It would however be correct to say that a dependence on Russian LNG does not have negative connotations for Lithuania, unlike Russian pipeline gas where Gazprom has an export monopoly.

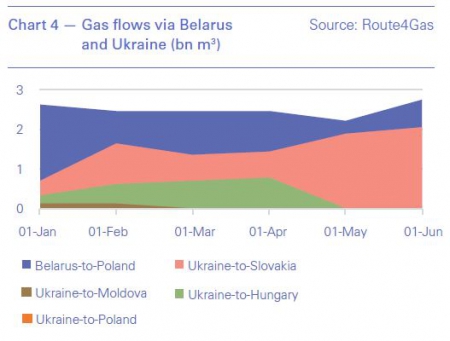

One may rightly argue that with 55bn m³/yr of capacity, Nord Stream 2 is not a game changer for Gazprom’s positions in Europe: the task remains to regain market share amid low prices, while the company has already sufficient export capacity at its disposal in Ukraine and Belarus. Table 1 illustrates that six months flows via Belarus and Ukraine combined already reach 30bn m³, while the transit capacity – particularly via Ukraine – remains underutilised. The transit agreement with Ukraine concluded towards the very end of last year enabled increased gas flows via Uzhgorod (Ukraine-Slovakia). Data reveal Gazprom’s increasing reliance on Yamal-Europe pipeline (Belarus-to-Poland), which effectively bypassed Ukraine during the observed period. A slight decline in flows in May might be explained by technical delays caused by Gazprom’s renewal of Polish pipeline capacity by Gazprom.

Would Nord Stream 2 have an effect if completed? Probably yes. The table also reveals the impact of Turk Stream on Russian gas flows via Ukraine-Moldova which significantly decreased and then stopped in May. It might be worth remarking that relations with Belarus and Ukraine transcend gas transit business. Political developments in the two countries, Russia’s foreign policy choices and tensions between Moscow and the west may only add political uncertainties to the economic ones.

|

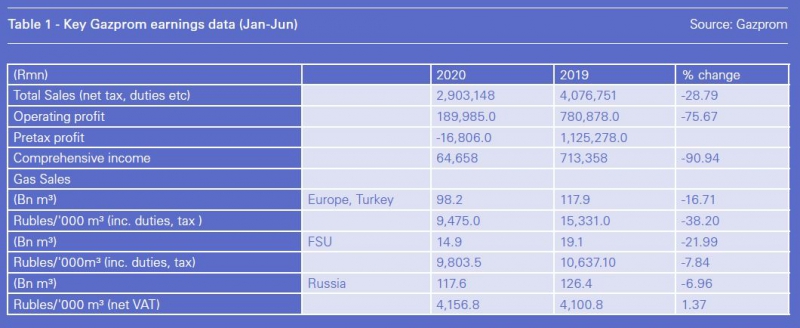

Gazprom’s dire second quarter Gazprom’s net income nearly halved in the second quarter to rubles 153.5bn ($2.1bn) from 319.1bn a year earlier as coronavirus (Covid-19) lockdowns in Europe took their toll. Revenues plunged 35% to rubles 1.16 trillion, and Gazprom swung to an operating loss of rubles 103bn, versus a rubles 322bn profit a year before. Core earnings (Ebitda) slumped to rubles 66.6bn ($1.3bn), versus $7.4bn a year earlier, with analysts at BCS Global Markets (BCS GM) describing this as the worst quarterly result in at least a dozen years. Gazprom's free cash flow was negative $1.8bn for the quarter, while its net debt crept up 9% to around $53bn, according to BCS GM. This led to its net debt to Ebitda ratio rising from 1.8 to 2.7. Gazprom's revenues from sales to Europe and other countries outside the former Soviet Union dropped 47% to rubles 756bn. Sales volumes were down 16.7% at 98.2bn m3, while average prices were down 38% at rubles 9,475/'000 m3. Gazprom's domestic business performed better, seeing only a 6% decline in revenues to rubles 488.7bn and only a 7% fall in volumes to 117.6bn m3. Gazprom's earnings were also affected by charges to reflect lower prices and a weaker ruble. But these charges were mostly booked in the first quarter, when Gazprom reported a $1.64bn loss. The table provides the data for the six months as a whole. Joseph Murphy |

*Route4Gas, which went live September 1, is an online trading system where an algorithm matches counterparties for day-ahead gas delivery within Europe in an anonymous auction. It couples physical and financial positions and products including storage, existing flow and unused capacity. Up to eight counterparties may become involved in different legs of a deal, and they take all the risk but pay a service fee to Route4Gas. They may then arrange capacity by bidding on the Prisma platform in a later daily auction.

Privately owned Vier Gas Transport (VGT) owns a quarter and management and private equity the rest. VGT CEO Stephan Kamphues, formerly a head of Gas Infrastructure Europe, said Route4Gas “fills a service gap regarding unbundled capacities in the European gas market” and fits “the current environment where digitalisation is the watchword.”