Africa to bear brunt of gas investment cuts: Tema LNG head [Gas in Transition]

If pressure continues to be put on investors not to invest in gas projects, this will have a “disproportionately negative effect on African countries,” says Kwaku Boakye Adjei, consultant and director of the Tema LNG terminal company in Ghana in an interview with NGW. He notes that upstream projects in Africa are already being hit by the negative sentiments around gas. “This is not going to be good for anybody. African countries will not turn to renewables if they can’t get access to gas. They will stick with heavy fuel oil and crude.”

According to Adjei, the “path to decarbonisation for Africa is different than for Europe. For Africa the most efficient path is through natural gas.” He says he is concerned about the impact of the International Energy Agency’s recent Net-Zero Roadmap, which calls for no new investment in upstream gas and oil projects anywhere in the world. He calls the recommendation “unfortunate.”

“This has a real impact on the ability of African companies to raise capital for upstream projects,” he says. “It is putting a lot of pressure on investors and banks.”

He warns that as a result of this pressure, “a lot of upstream projects are already being made impossible. It is making it difficult to raise money. It’s going to be a struggle to see large new upstream projects coming on stream in Africa. This will have a disproportionately negative effect on African countries.”

The problem is that this will not only be bad for the economy, but for the climate as well, says Adjei. “It’s not going to be good for anybody. The response of African countries will not be: we are going to develop renewables instead. Their response is going to be: let’s stick with heavy fuel oil and crude.”

Eurocentric

According to Adjei, the “broad position” taken by the IEA – “without the caveats you would expect” – represents a “very Eurocentric view of the world”. The IEA is failing to make a distinction between the circumstances around decarbonisation different continents and countries find themselves in, says Adjei. “You have entities based in and around European countries that are dictating to African countries how they should develop, without a clear understanding of the problems that we face.”

Adjei explains that African countries are faced with very different challenges than countries in Europe. “In Europe the production of electricity through fossil fuels was already at a very high level. They had to replace existing production with renewable alternatives. This was made easier over time as much of the capex was paid for with subsidies.” In Africa, the situation is very different. “The kWh consumption per capita is very low. Most of the electricity is produced with crude oil and diesel. And significant amounts are lost through transmission losses.”

Since the problems are different, the solutions need to be different too, says Adjei. “African countries don’t have the economic power to provide significant financial support to renewables. And consumption is too low to support large-scale renewable energy projects.” Renewables is an economy-of-scale business, he adds. “You need large-sized projects to get economies of scale. In many African countries the demand is not there, so you can’t deliver large-scale projects that deliver economies of scale. Instead you get small-scale projects that are high in cost, with low returns, which require large subsidies.”’

Adjei is convinced that the solution for Africa is to be found in natural gas. “Gas is an obvious transition fuel. When you switch from oil to gas in electricity generation you reduce emissions by 30 to 35%. With LNG trucked directly to consumers, you also help reduce transmission losses. These are up to 50% in some countries. The great thing about gas is that it also creates a baseload that allows you to feed in renewable energy without worrying about intermittency. The two are complementary.”

Thus, with gas, “Africa can get 60 to 70% lower emissions in a way which doesn’t require large amounts of capital support and which generates economic development.” He stresses the need for economic development in Africa. “If we do things that do not generate economic development, countries are asked to make a horrible choice: between a low-carbon future or a future with economic development. Any government that is given that choice is going to struggle to reduce emissions.”

Attractive price

If Africa turns to gas, will it become an importer or producer – or even exporter? Adjei says it will be a “mix”. “Gas is a resource we have in the region. This is important because the possibility of sourcing locally and reducing shipping costs is part of achieving an attractive LNG price. But countries that don’t have access to associated gas are going to be natural importers. There will be supplies of LNG coming from both the west and east coasts of Africa.”

Adjei explains that for a country like Ghana the breakeven price of delivering gas from offshore projects over 1,200 m of water depth is the same as for oil, around $50-$55/barrel. “If you convert that into gas it’s $9-10/mn Btu at the wellhead. If you look at the cost of LNG delivered into Ghana it’s significantly lower than that. So Ghana is an example of a country that has its own resources but it’s still efficient for it to blend them with imports of LNG. If countries don’t have access to cheap associated gas they will likely be importers of LNG.”

Adjei explains that for a country like Ghana the breakeven price of delivering gas from offshore projects over 1,200 m of water depth is the same as for oil, around $50-$55/barrel. “If you convert that into gas it’s $9-10/mn Btu at the wellhead. If you look at the cost of LNG delivered into Ghana it’s significantly lower than that. So Ghana is an example of a country that has its own resources but it’s still efficient for it to blend them with imports of LNG. If countries don’t have access to cheap associated gas they will likely be importers of LNG.”

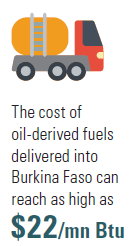

In a country like Burkina Faso, which is landlocked and has small demand, “they are suffocated by the premiums they pay for fuels and diesel oil for power generation. They are paying $20-22/mn Btu for fuels. We are able to deliver LNG to them at half the price. I believe all African countries will be able to benefit from the low-cost gas we can supply and the infrastructure we can build.”

What does Adjei think of the German plans to invest in West-African countries to develop green hydrogen projects for export to Europe? “I am positive about this idea. To have a flexible and varied energy mix is good.” But, he adds, “there are lots of questions about whether the renewable energy sector is currently driven by decarbonisation or value creation. If the question is, would it be more efficient to develop renewable energy projects in and for Africa, with all of the attendant benefits, the answer is yes.”

|

“Net zero? Not for Africa. Not yet.” Adjei is not the only one who is concerned about the impact of the IEA’s call to end investment in new fossil fuel projects. N.J. Ayuk, Executive Chairman of the African Energy Chamber, wrote a highly critical response to the IEA’s Net-Zero Roadmap in African News. Ayuk points out that the IEA’s roadmap to net zero “relies on unprecedented investments in renewables — a substantial boost in clean energy investments from the $1 trillion made over the last five years all the way up to $5 trillion annually by 2030 — and cooperation from policymakers who are unified in their efforts. In this idyllic partnership, our Western counterparts talk a good game. But the fact is, to date, these same Western countries have invested little to no funding into Africa's renewables space. To our dismay even the international oil companies that have tried to accept the IEA’s publicity stunt have little or no renewable projects in Africa.” The IEA plan “amounts to austerity measures that would see Africans leaving petroleum resources in the ground. It would essentially brand poor Africans criminals — or at the very least enemies of the environment — for using fossil fuels,” writes Ayuk, who calls this “folly”. He points to “the critical role that natural gas is playing in the global transition to clean energy: It’s an affordable and reliable bridge to renewables. And natural gas is particularly important to Africa … the African Energy Chamber’s 2021 Africa Energy Outlook report projects that African gas production and consumption are going to rise in the 2020s. As a result, Africa’s natural gas sector will soon be responsible for large-scale job creation, increased opportunities for monetisation and economic diversification, and critical gas-to-power initiatives that will bring more Africans reliable electricity.” He writes that “these significant benefits should not be dismissed in the name of achieving net zero emissions on deadline. To tell African countries with gas potential like Mozambique, Tanzania, Equatorial Guinea, Nigeria, Senegal, Libya, Algeria, South Africa, Angola and many others that they can’t monetise their gas and rather wait for foreign aid and handouts from their western counterparts makes no sense.” |

Who is Kwaku Boakye Adjei?

Kwaku Boakye Adjei, a Ghanaian national who lives in Luxembourg, started his career in oil and gas 20 years ago with BG Group. After that, he worked for RWE, Tullow and Faroe Petroleum, before he became an independent consultant for private equity investors and banks. In 2018, he partnered with Helios Investment Partners to help build the Tema LNG terminal in Ghana. At the time of this writing, the Tema terminal was being commissioned and expecting to receive its very first cargo, from Shell.