Africa’s natural gas production [NGW Magazine]

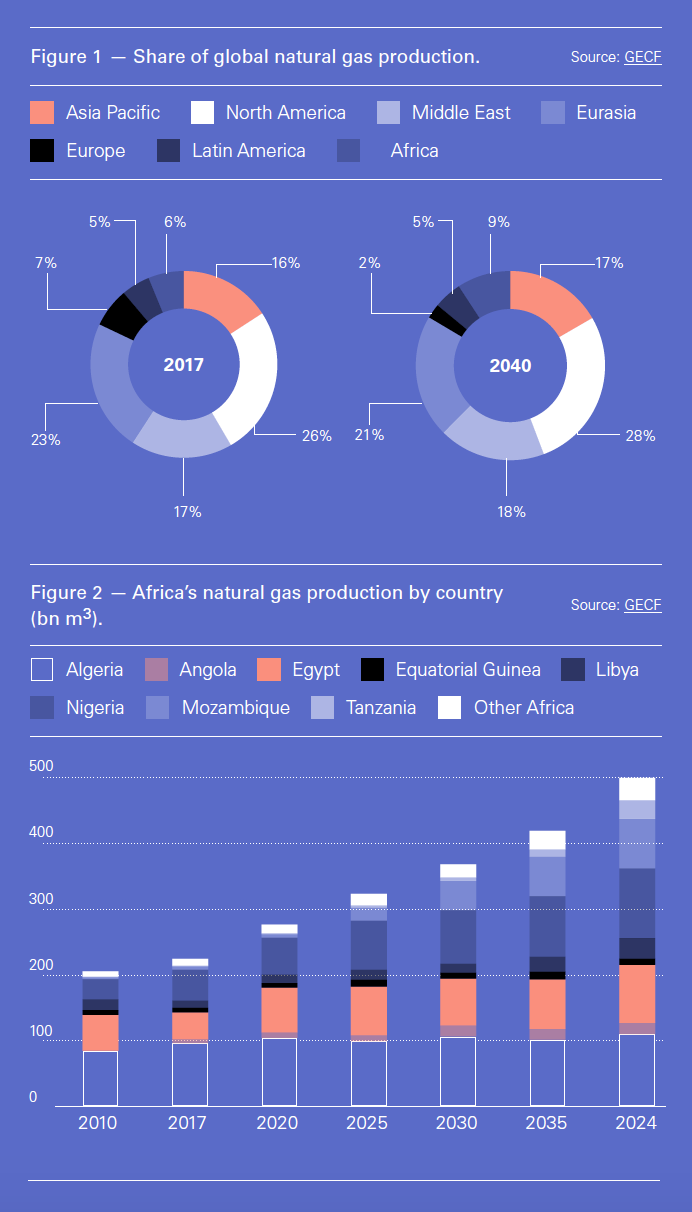

One of the most recent outlooks, published October 2018 by the Gas Exporting Countries Forum (GECF), forecasts that natural gas production in Africa will increase from about 230bn m³ in 2017 to about 500bn m³ by 2040. This means that by 2040 Africa will be providing about 9% of global gas supply, compared with 6% now (Figure 1).

With BP estimating Africa’s total proved reserves to be about 13.8 trillion m³, over 7% of global reserves, Africa has considerable potential awaiting development. About four-fifths of these reserves are in four countries: Nigeria, Algeria, Egypt and Libya. But BP’s estimates do not include the most recent discoveries in Mozambique, Egypt and Tanzania, which once proved could add over 4 trillion m³ to this total.

With such rapidly growing gas potential, the focus in Africa is shifting from oil to gas production. This is partnering renewables in electricity production, but is also boosting exports creating much needed revenue. Gas is also addressing Africa’s burgeoning electricity and energy needs.

Production and consumption outlook

Africa’s historical and forecast natural gas production is shown in Figure 2 by country. About 90% of this is produced by Algeria, Egypt and Nigeria.

With Algerian output expected to barely move, most of the future expansion will come from Mozambique, Egypt and Nigeria. Tanzania is also expected to come up strong, but with smaller quantities.

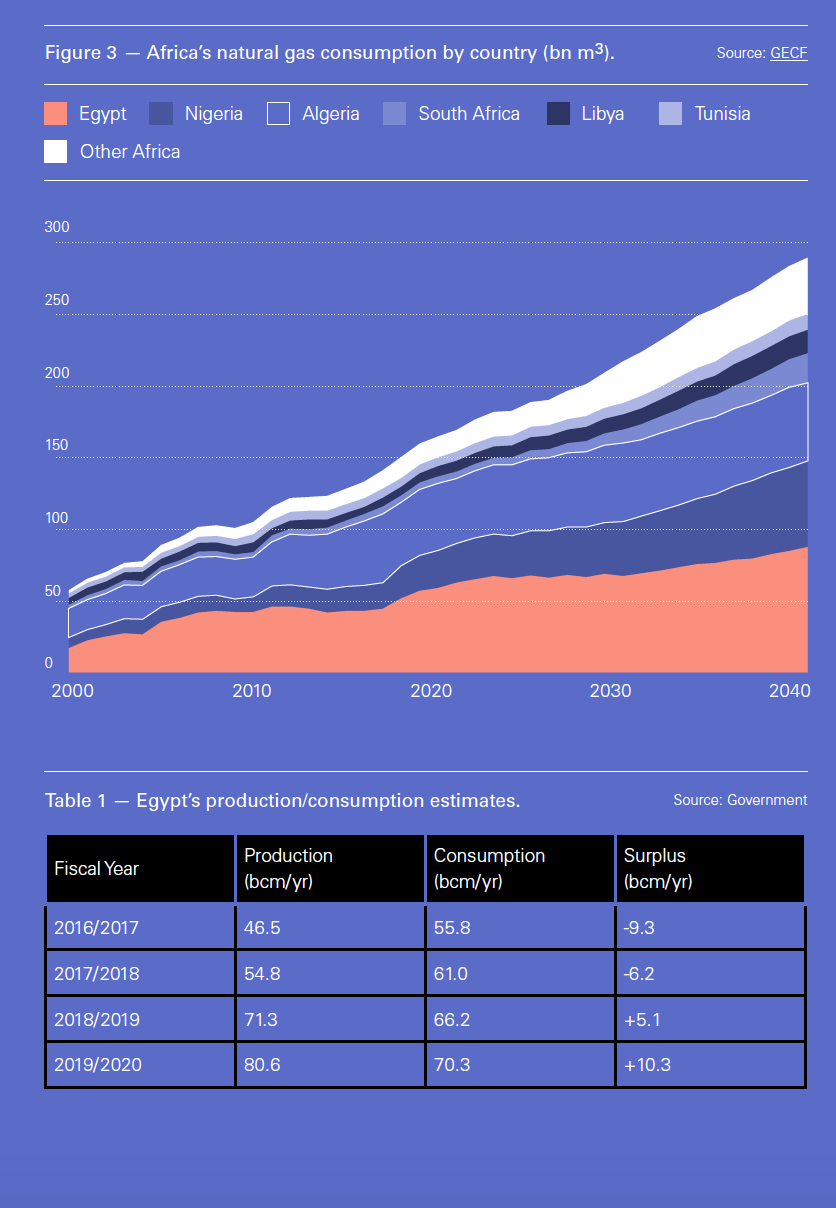

Africa’s forecast natural gas consumption of about 278bn m³/yr by 2040 is being led by Egypt, with about 30% (Figure 3). However, the important observation from comparison of Figures 2 and 3 is that, despite its population increasing by almost two-thirds and GDP more than doubling by 2040, Africa will continue being a net exporter of natural gas, with surplus production over demand of over 220bn m³/yr by 2040.

New gas provinces Mozambique and Tanzania saw major new gas discoveries over the last few years, with potentially more to come, and are expected to contribute substantially to this.

A significant factor behind this is the increasing penetration of renewables, expected in BP’s Energy Outlook to be providing a tenth of Africa’s primary energy demand by 2040, from 1% in 2016. By comparison, natural gas will contribute 30%, instead of 28%. With renewable energy providing a bigger share of Africa’s primary energy by 2040, it frees more natural gas for export.

A significant factor behind this is the increasing penetration of renewables, expected in BP’s Energy Outlook to be providing a tenth of Africa’s primary energy demand by 2040, from 1% in 2016. By comparison, natural gas will contribute 30%, instead of 28%. With renewable energy providing a bigger share of Africa’s primary energy by 2040, it frees more natural gas for export.

Algeria

Algeria is the largest natural gas producer in Africa. According to BP data it produced 91bn m³ in 2017 and should achieve about the same in 2018. This is supported by 4.3 trillion m³ proved gas reserves.

Algeria also holds the third largest shale gas resources in the world, estimated to be more than 22 trillion m³. But there are major challenges and population resistance to be overcome before any exploitation can start. It will take time.

Sonatrach’s chairman A. Ould Kaddour has been addressing this problem since his appointment in March 2017 when he oversaw the drafting of a new strategy, SH 2030, outlining the company’s priorities and objectives for the next decade.

But many are asking whether it can be implemented. Political meddling, red tape, inefficiency, delays and corruption are the big challenges to be overcome in a country and an organisation that have both historically proved resistant to reform.

Algeria is Europe’s biggest natural gas supplier by pipeline, after Russia and Norway. In total, Algeria exported 49.3bn m³ gas by pipeline and LNG in 2017 and of that, a third was LNG. In addition, it exported about 5bn m³ to Morocco and Tunisia. The remainder of the gas it produced was taken up to satisfy Algeria’s domestic demand. This has been increasing at a rate close to 5%/year, leading to market concerns about the impact on exports of rising domestic demand and the foot-dragging when it comes to bringing Algeria’s vast gas deposits to market.

This is where Algeria’s challenges to the future of its gas exports may lie. It is using more and more of its own gas at subsidized prices and without significant new discoveries, these are impacting Algeria’s ability to maintain exports.

However, in March 2018 Total started gas production at the Timimoun gas-field, at about 1.8bn m³/yr. Sonatrach raised production at the Alrar gas-field close to its border with Libya from 5.8 to 9bn m³/yr in July last year. In addition, it has just announced that the Touat gas-field will come on stream in February adding 4.5bn m³/yr to Algeria’s gas production. These will contribute to Sonatrach’s stated intention to sell more gas to Europe, and to Spain in particular.

It is Spain rather than its other pipeline customer Italy that is the target. Italy has strong gas ties with Russia and will soon be receiving gas from Azerbaijan. Sonatrach extended its gas supply contract with Spain’s Naturgy mid-2018, with the potential to supply 40% of the Spanish company’s needs to 2030.

Given the importance of gas supplies to Europe, EU climate and energy commissioner, Miguel Arias Canete, visited Algeria in November 2018, where he had high level meetings to revive the energy partnership between the EU and Algeria.

In another development. Sonatrach, Eni and Total signed two agreements last October for offshore exploration in Algeria. Eni's CEO Claudio Descalzi said: “Together with Sonatrach and Total, we will have the opportunity to explore the deep waters of the Algerian offshore, a virtually unexplored geological province where Eni will be able to contribute by leveraging its experience in the eastern Mediterranean and its inventory of advanced exploration technologies.”

But with no new gas-fields expected to come on stream by 2020, following Touat, and more gas being used at home, Algeria will struggle to increase, or even maintain, gas exports.

Egypt

According to BP data, Egypt’s proved natural gas reserves total 1.8 trillion m³. But again, this does not yet include the more recent discoveries, even Zohr which has 850bn m³ estimated gas in place. Egypt is also optimistic that there is much more gas still to be discovered in its offshore fields, particularly in the Mediterranean.

The country is the second largest producer and largest natural gas consumer in Africa. According to BP data it produced 49bn m³ in 2017. But it consumed more gas than it produced in 2017, at 56bn m³, with the difference imported as LNG.

However, with increasing production from Zohr, Egypt achieved self-sufficiency in gas in September 2018, enabling the resumption of LNG exports. By early January LNG exports from Shell’s Idku liquefaction plant reached the equivalent of 5.5bn m³/yr.

The Zohr development is progressing at a fast pace. First gas was achieved in December 2017, just 28 months after discovery – a world record. It achieved 20bn m³/yr equivalent production in October last year and it is now expected to reach a plateau production of 33bn m³/yr later this year. This is higher than the original plan by 5bn m³/yr.

This additional gas is likely to go to the Damietta LNG plant for export, following the settlement of the arbitration with Union Fenosa.

Based on expected gas production and consumption, Egypt’s petroleum ministry estimates that by 2020 there will be over 10bn m³/yr surplus gas available for export (Table 1).

This may grow to 15bn m³ once Zohr achieves the revised production plateau. Based on this, Egypt has agreed to restore 2.5bn m³/yr gas exports to Jordan, which restarted in September 2018.

And it is not just Zohr. There are many small gas-field discoveries that keep coming. There is more gas to come from recent and new discoveries: Balteem, 9B, Raven, East Obayed and South Disouq. These are small but could add up to about 15bn m³/yr.

In addition, Eni, and its partner Tharwa Petroleum, should be announcing the results of drilling at the promising Noor concession 50 km offshore the Sinai peninsula in January – initial estimates put the field’s reserves at about 280bn m³. In November Eni sold off two stakes in the field, 20% to UAE’s Mubadala Petroleum and 25% to BP.

With yet-to-find gas estimated to be anywhere between 1.4 and 4.25 trillion m³, a plethora of other smaller natural gas fields under developed and the problem of late government payments for the offtake being a thing of the past, Egypt’s gas production has the potential to rise substantially.

Demonstrating its confidence in future gas discoveries, Egypt has developed a new model oil and natural gas production contract allowing international oil companies (IOCs) to sell their share of output to whoever they wish.

Eni, Shell, BP and Edison announced plans to expand their existing investments and activities in Egypt. BP actually invested $35bin during the last 5 years, with another $16bn coming from Eni.

Egypt is planning new licensing rounds this year in the Red Sea and the Mediterranean. The western part of Egypt’s exclusive economic zone in the Mediterranean is largely unexplored and very promising.

The country has liberalised its gas market, but this is at an early stage of implementation. However, it has paved the way for private companies to import gas, such as Dolphinus that hopes to start importing Israeli gas. But much more needs to be done before the gas liberalisation law becomes fully implemented. State marketing agency Egas estimates full implementation by 2022-23. Fuel subsidies are also gradually being removed.

Egypt is also successfully expanding renewable generation, solar and wind, with a target to achieve 20% renewable electricity by 2022. It is also expanding coal and nuclear power generation. These should make natural gas available for export.

On the back of these developments Egypt aspires to become the eastern Mediterranean’s energy hub, with World Bank support.

Libya

According to BP data, Libya’s proved natural gas reserves total 1.4 trillion m³. It produced 11.5bn m³ in 2017, of which about 4.5bn m³ went to Italy by pipeline. Gas production and export was maintained at similar levels in 2018.

Even though this is just under half its pre-2011 levels, amazingly the country has been able to continue uninterrupted exports since then, despite the massive upheaval and security challenges it is going through.

It has even been able to start new gas production offshore. A joint venture between Libya's National Oil Corp. (NOC) and Eni started production at the second phase of the Bahr Essalam project off the coast of Libya in July 2018. The gas is delivered to an onshore treatment plant and then into the national supply chain. Mustafa Sanalla, chairman of NOC, said the startup shows that IOCs remain confident about working in the country.

With completion of phase 2 by the end of 2018, Bahr Essalam is expected to add 4bn m³/yr which will be used in the power sector. It will bring Libya’s total production to over 11bn m³/yr.

Sanalla said that improved security conditions in the Sirte Basin in central Libya will enable the launch of production at the Farigh gas-field in three months, initially at 0.25bn m³/yr, with a target to eventually increase this to 2.8bn m³/yr.

The country still remains highly vulnerable to upheavals and disruption. With legislative elections planned to take place this year, problems may worsen as rival factions vie for position.

But IOCs, such as BP and Eni, recently announced their intention to resume exploration activities, while Austrian OMV and Spanish Repsol are also hoping to increase their upstream presence. Hopefully the elections will result in a political solution that allows Libya to build on and sustain its recent oil and gas recovery – but it will not be easy.

Mozambique

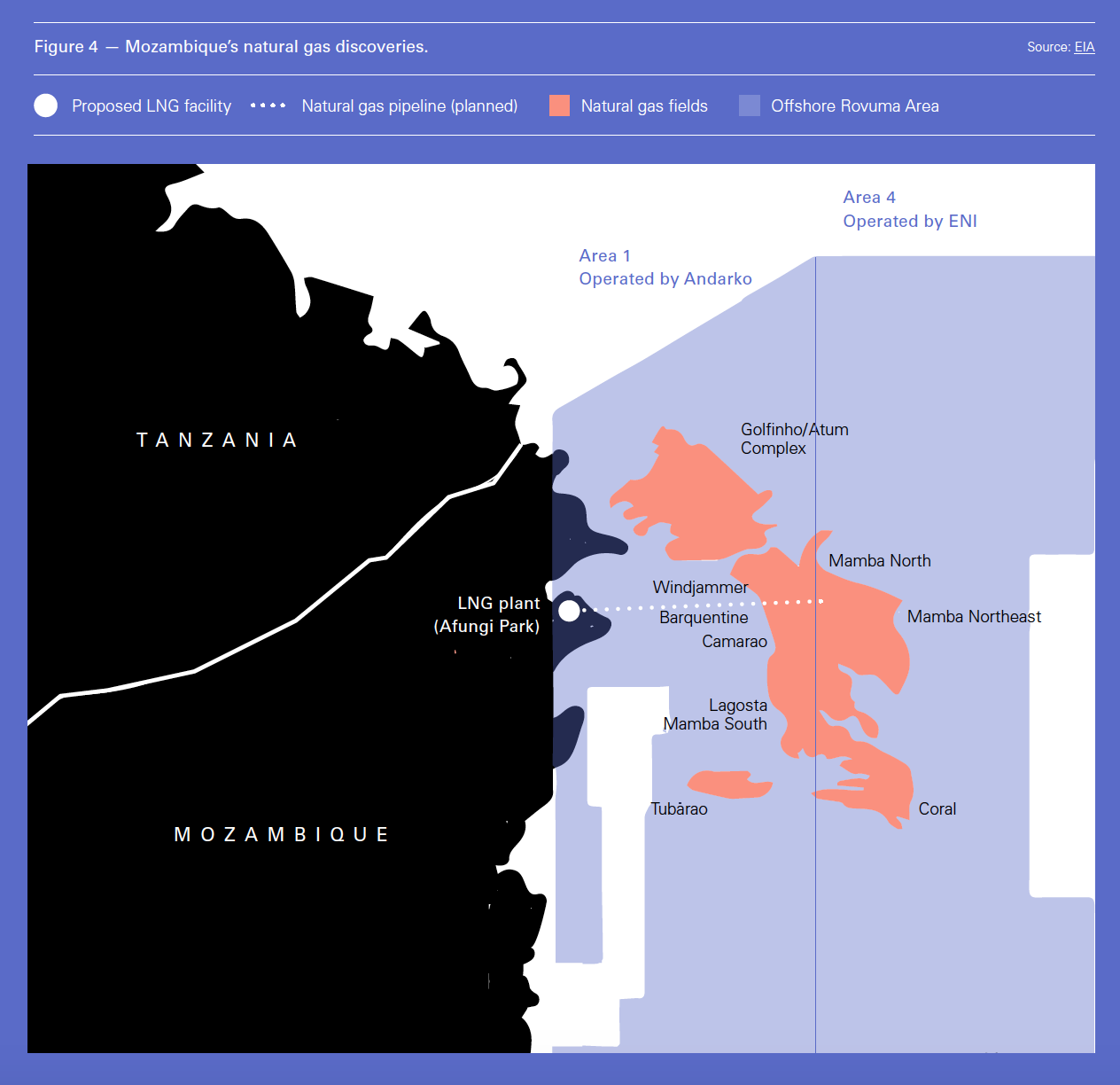

Mozambique’s estimated gas reserves total over 5 trillion m³, mostly discovered in the very prolific Area 1 and Area 4 of the Rovumba river basin (Figure 5). These place the country’s reserves on par with Nigeria, but there are strong indications that they could rise close to 8 trillion m³ by 2030.

South African Sasol has been producing gas in Mozambique since 2004, exporting most of it by pipeline to power plants back home.

Anadarko Petroleum received official approval from the government of Mozambique in March 2018 for its Golfinho/Atum field development plan in its Area 1 deepwater block. This is estimated to hold about 2.1 trillion m³ gas reserves. The company is now in the process of launching a greenfield LNG project, Mozambique LNG, to initially produce 12.9mn mt/yr at a total estimated cost of $25bn.

Anadarko and its partners intend to expand the plant by adding more capacity every five years, with the potential to reach up to 50mn mt/yr in future.

With Anadarko’s announcement end of June that it is set to make a final investment decision (FID) on its large LNG project during the first half of 2019, Mozambique is well on the way to becoming a new, major, gas province.

However, the first successful launch of a natural gas project in Mozambique is the development of Coral South gas-field. Coral South is inside the Mamba Complex in Area 4 and it is being developed by Eni as the operator.

The field is in over 2,000 metres of water and has over 450bn m³ of gas. FID was reached end May 2017 for a floating LNG facility (FLNG) with 3.4mn mt/yr capacity, expected to start producing in 2022. Total project cost is estimated to be $10bn. It did so after securing a purchase contract with BP in 2016, which bought all LNG production for 20 years.

And that’s not where it ends. ExxonMobil, having come into Area 4 last year, by joining Coral South FLNG, has breathed life into a project to construct an onshore LNG plant, Rovuma LNG, at Cabo Delgado to develop Area 4 reserves.

The initial phase of the Rovuma LNG project will involve development of the Mamba reservoirs with an estimated 2.4 trillion m³ gas, to produce, liquefy and sell natural gas. ExxonMobil will lead construction and operation of 2x7.6 mn mt/yr liquefaction trains and related onshore facilities and Eni will lead upstream developments and operations. Total cost is estimated to be $30bn.

Rovuma LNG confirmed in December that it has already secured LNG offtake commitments from affiliated buyer entities of the project partners. This is a key milestone that will enable the project to achieve FID in 2019.

Through these projects, Mozambique could achieve 32 mn mt/yr LNG export capacity by the mid-2020s, becoming the world’s sixth-largest LNG producer.

But important challenges to overcome are security concerns and corruption. An indictment this month in the US related to a scheme for government officials to siphon millions of dollars in briberies has brought this back to the fore. Much needs to be done if natural gas is not to do to Mozambique what oil has done to Nigeria.

However, many see Mozambique as the next big frontier for LNG development. The country also hopes that development of its offshore fields will provide gas to support domestic needs, power generation and petrochemical plants.

Nigeria

According to BP data, Nigeria is the 17th largest natural gas producer in the world, and ranks 12th in terms of LNG exports. Gas production, at 47bn m³/yr in 2017, is surprisingly low in comparison to its 5.2 trillion m³ proved gas reserves – ninth globally and the largest in Africa. In comparison, China with similar reserves, 5.5 trillion m³, is producing over three times as much gas: 149bn m³/yr. In 2017 Nigeria used about 19bn m³ gas, mostly for power generation.

On its website, Nigeria National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) states: “NNPC's vision is to make Nigeria the leading LNG producing nation in the world and to promote sufficiency in the domestic power supply. We intend to achieve this goal by monitoring the commercialisation of Nigeria’s abundant natural gas reserves, reducing gas flaring, promoting viable LNG projects, power plants and associated gas projects.” Admirable, but so far Nigeria has been singularly unable to deliver anything close to this.

Nigeria's oil and natural gas industry is primarily located in the southern Niger Delta area, where it has been a source of conflict leading to disruption, vandalism and chronic security challenges. Even though oil and gas provide close to 60% of government revenues, endemic inefficiency and corruption have prevented Nigeria from fully benefiting from these resources.

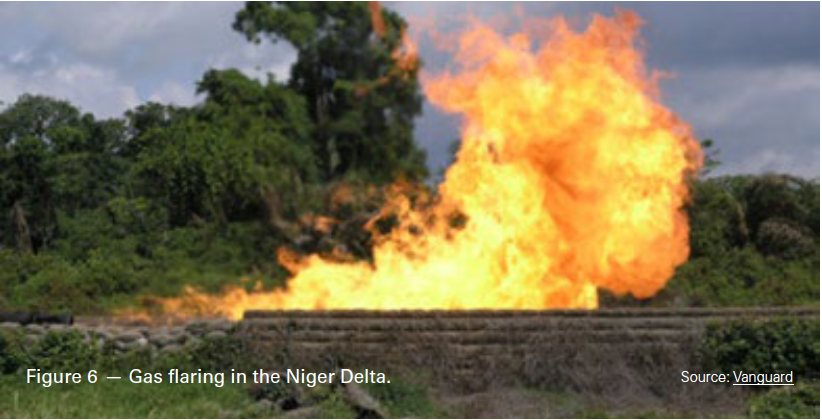

Other major problems include gas flaring associated with oil extraction, ageing infrastructure and poor maintenance. Despite frequent promises to eliminate it, flaring is still being practiced at large scale (Figure 6). NNPC estimates that over 20mn m³ are being flared daily, about 15% of production, that results in the emission of about 16mn mt/yr of CO2. Despite years of addressing the issue, gas flaring continues and contributes to severe air pollution in the region. It does not appear to be a problem that will go away soon.

The government is committed to addressing both corruption and gas flaring, but with limited success so far. It will take time.

However, despite challenges, Nigeria LNG (NLNG) has been a rare success story, providing over 7% of the world’s LNG supplies. In 2017 it exported 21.3 mn mt. With the country planning to expand LNG exports, with $7bn new gas projects being commissioned, it has every chance of continuing as a major LNG player.

Tanzania

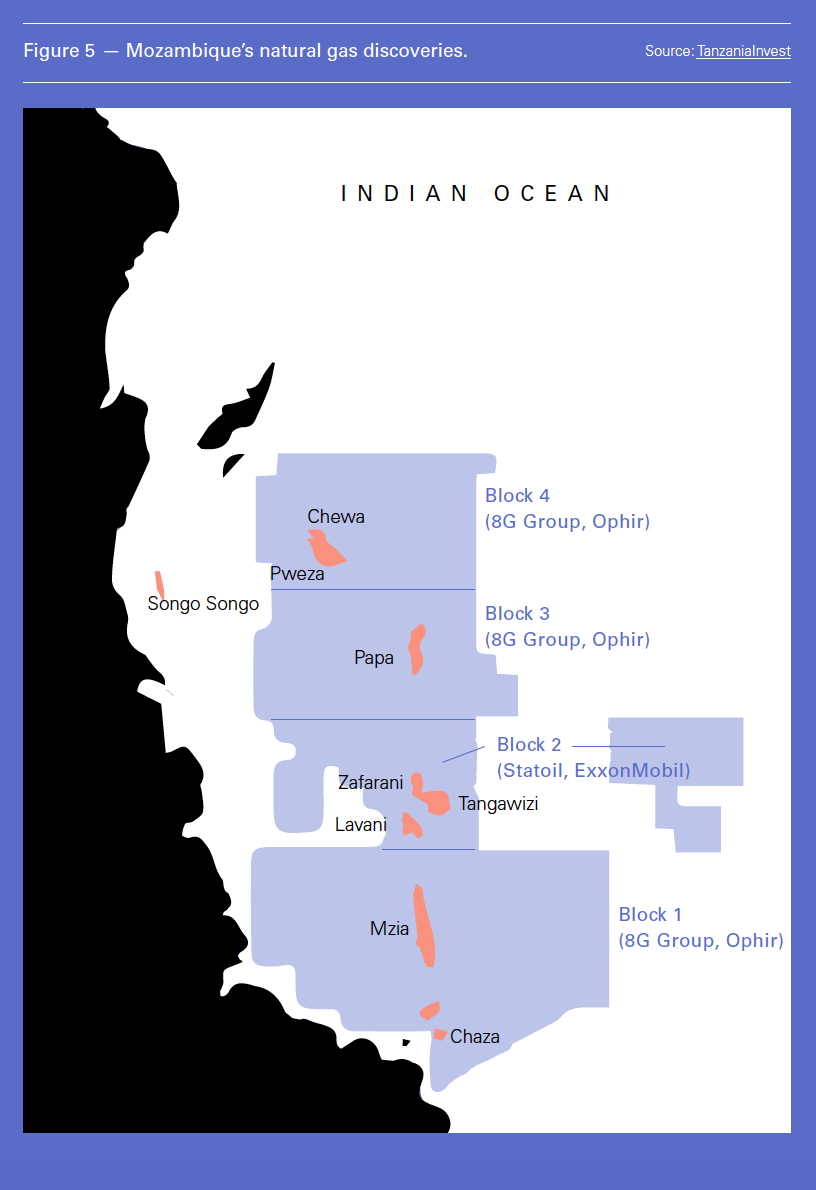

Tanzania started producing natural gas in 2004 from Songo-Songo and in 2006 from Mnazi Bay (Figure 7) that enabled the country to pursue an aggressive gas-to-power development to the benefit of its economy. According to the Tanzania Petroleum Development Corporation (TPDC), domestic demand for natural gas has now risen to over 3bn m³/yr.

A total of about 1.56 trillion m³ natural gas is estimated to have been discovered, with the potential to grow further. Out of this, about 300bn m³ have been allocated for domestic electricity production and industrial use.

The remainder has been allocated for the development of an LNG project by a consortium that includes Anglo-Dutch Shell, UK Ophir, Norway’s Equinor, US ExxonMobil and Singaporean Pavilion, estimated to cost $30bn. However, even though negotiations started in 2017, the government and the consortium still have differences to resolve in agreeing terms and the project has slowed down.

The government’s hardline approach and policy uncertainties slowed down progress in Tanzania’s natural gas sector in 2018.

But in December 2018 Tanzania’s president allowed negotiations to resume. The consortium also confirmed that it is co-operating with the government and that it is ready to move forward. Shell said that the focus is on agreeing the host government agreement that is to set the legislative, regulatory and fiscal terms for the project. But there is still some way to go before project realization and LNG exports, probably in the mid-2020s.

Equinor is the operator and holds the majority of the working interest in block 2, with Exxon Mobil holding a 35% stake. Shell and Ophir hold interests in Tanzania’s blocks 1 and 4.

By the end of 2018 there was renewed urgency, with the government and the companies confirming that they are ready to proceed with the negotiations.

Others

Angola and Equatorial Guinea are estimated to have gas resources of about 510bn m³ and 367bn m³, respectively. Both countries have very low domestic demand, which enables them to export most of their gas as LNG. Angola achieved 3.7 mn mt LNG exports in 2017 and Equatorial Guinea 3.6 mn mt.

Angola’s new president Joao Lourenco made it clear early in 2019 that he intends to reform Sonangol by focusing it on upstream operations, something which is badly needed. This follows the decision last August to create a National Oil and Gas Agency (ANPG) to conduct and manage the country’s oil and gas licensing rounds. A new policy will also give licence-holders control over the natural gas resources within their licences. This could drive a renewed expansion of the gas sector beyond Angola LNG.

On the other hand, Equatorial Guinea ran out of patience with oil and gas operators and in September 2018 demanded that they either proceed with drilling in 2019 or move out. This appears to have paid off, with $2.4bn new investment agreed between the government and ExxonMobil, Noble Energy, Kosmos Energy and Marathon Oil for drilling and increasing production. But for Ophir time ran out early in 2019 when the government denied extending its licence for block R and the Fortuna gas-field, where the company had plans to install a deepwater FLNG.

Equatorial Guinea is planning to capitalise on these developments in 2019, which it has declared as the ‘Year of Energy’, with a number of rigs already contracted to drill 11 new wells.

Since March 2018 Cameroon became one of the latest LNG producers. Perenco and Golar’s Hilli Episeyo FLNG vessel 20 km offshore Kribi started production in March 2018. Its liquefaction capacity is 1.2 mn mt/yr LNG and the off-taker is Gazprom. The plan is that this will be followed by a land-based LNG plant north of Kribi port. In addition, NewAge LNG is planning a second FLNG facility at the Etinde block with 1.3mn mt/yr capacity, expected to start operations in 2023.

NewAge LNG is also planning a smaller 1.2mn mt/yr FLNG project offshore Congo-Brazzaville, also to come online in 2023.

Ethiopia’s Ogaden Basin is estimated to hold 226bn m³ natural gas reserves. China Poly Group Corp. has been developing oil and gas fields in Hilala and Calub. Gas production started in 2013 and crude oil production mid-2018. The government estimates initial annual income of $1.2bn/yr when gas exports begin, expected to rise to up to $7bn/yr.

Ghana has been producing oil since 2010, but started receiving gas from its own gas-fields for the first time last year. In July 2018 Eni started gas production at the Sankofa fields, part of the Offshore Cape Three Points (OCTP) Integrated Oil and Gas Project. It will provide about 1.8bn m³/yr for 15 years, with a plan to increase this to 2.6bn m³/yr. Gas production has also started during the second half of 2018 at the Tweneboa, Enyenra and Ntomme (TEN) field operated by Tullow.

Ghana is in the process of conducting a new offshore licensing round. Rising domestic demand for gas in power generation is expected to boost gas exploration.

Ivory Coast has been producing small quantities of natural gas, about 2.5bn m³/yr in 2017. It awarded a number of oil and gas blocks to Tullow in 2018 and hopes to double gas production by 2020.

Mauritania and Senegal are new additions to the increasing list of African countries with new gas discoveries. BP and Kosmos took FID in December and are proceeding with an FLNG option for the 530bn m³ Tortue/Ahmeyin field development, offshore Mauritania and Senegal. Golar was issued with a ‘limited notice to proceed’ in December for an FLNG vessel for phase 1 of the project, with a capacity to produce 2.4mn mt/yr LNG. This is expected to start production in 2022.

South Africa is believed to potentially have vast shale gas reserves in the Karoo region. The EIA estimates that Karoo’s technically recoverable resources could be as much as 11 trillion m³, making it the second-largest in Africa, behind Algeria.

The government needs to decide on environmental issues, royalties and state shareholding, so that it can pass enabling legislation to award exploration licenses. But studies indicating that the shale gas deposits may be less than originally estimated and environmental objections are still delaying the process.

In the meanwhile, South Africa’s energy minister published in August a new long-term vision to reduce coal consumption and increase renewables and gas, with the latter targeted to provide 16% of the country’s energy mix by 2030, from 1% now. A potential source of such gas is neighbouring Mozambique.

Across Africa governments are increasing their efforts to discover and develop natural gas resources to enhance power generation capacity and benefit from exports. However, there could also be risks associated with this, such as the natural resource ‘curse’ and corruption. But with proper planning, new discoveries can attract foreign investment, drive economic growth and dramatically raise living standards.

.png_f1920x300q80.jpg)