Algeria’s arduous search for investors [Gas in Transition]

Algeria is looking to open its oil and gas sector to greater foreign investment, in the hope of reversing production decline. But while there have been welcome signs of progress, including the introduction of more attractive hydrocarbon legislation in late 2019, there have also been more troubling developments. Decision-making at state energy institutions has been disrupted by frequent reshuffles of officials, and most recently, a $1bn dispute has broken out between national oil company (NOC) Sonatrach and an international partner.

Reform

Years of underinvestment and project delays have seen Algerian oil output decline from a peak of 1.4mn barrels/day in 2008 to around 1mn b/d in early 2020. Marketable gas supply has also been on a downward trajectory for several years, totalling 87.7bn m3 in 2020. This has squeezed the domestic gas balance and limited volumes available for export.

These trends are a considerable concern for the government, which relies on oil and gas for 60% of Algeria’s state budget and 94% of the country’s total exports.

The case for legislative reform to encourage investment has been set out by Sonatrach itself on many occasions. The company, which wants to expand its output and reserves significantly as part of its 2030 strategy, said in October 2019 that the overhaul of the hydrocarbon law was “essential to restore the attractiveness of the sector in the context of low oil prices and increased competition among producing countries to attract new investors.”

Two months later the government’s new hydrocarbon law was officially introduced. The new legislation marks a return to the attractive provisions in Algeria’s 1986 hydrocarbon laws, which led to a number of major discoveries before regulations were changed in the mid-2000s, sapping investment.

“The new hydrocarbons law has shifted the needle positively for existent and would-be investors,” Anthony Skinner, director for Middle East and North Africa at Verisk Maplecroft, tells NGW. However, international oil companies (IOCs) are still waiting for the implementation texts to be passed through parliament following the June 2021 general elections.

Furthermore, the law “cannot be treated in isolation,” he notes. “It has been overshadowed by Covid-19, sub-optimal oil and gas prices, churn in Algeria’s state energy institutions and concerns about the ability of the regime to manage mass-disenchantment.”

Signalling renewed interest in Algeria, Sonatrach has signed a number of memoranda of understanding with foreign upstream partners since the new law’s announcement. The signatories include US firms Chevron, ExxonMobil and Occidental Petroleum, Spain’s Cepsa, Italy’s Eni, Austria’s OMV, Russia’s Lukoil and Zarubezhneft, France’s Total and Turkey’s TPAO. These deals, though non-binding, are “the direct result of the amended hydrocarbons law being passed,” Skinner believes.

Still, the law is no “silver bullet,” the expert notes.

“On the positive side, investors welcome the greater selection of business contracts under the amended legislation,” he says. “Whereas the old law required permits to be offered under concession terms, the amended law gives contractors the option to select between participation contract (concession), production-sharing or risk service contract terms.”

IOCs can now carry out prospecting work in allocated areas and in the event of a discovery, they can formulate a research plan and secure a contract.

“Critics of the law says it does not go far enough to precipitate a big flow of new upstream investment to Algeria,” Skinner explains. “Under the legislation Sonatrach retains its right to a 51% stake in participation contracts in JVs.”

Regular reshuffles

Investors also have to contend with a “regular churn among executives” at state energy institutions, most notably at Sonatrach and the energy ministry.

“The lack of continuity at the helm of Sonatrach has given rise to a regular reshuffle of vice-presidents and disrupted decision-making as these individuals come to grips with their new portfolios,” Skinner explains. “Since the beginning of 2019, the NOC has had four chief executives, three of which have been replaced as a result of factionalism, ineffectiveness in their roles or a combination of both. This challenge has been exacerbated by long-standing realities: heavy bureaucracy and unpredictable decision-making.”

“The lack of continuity at the helm of Sonatrach has given rise to a regular reshuffle of vice-presidents and disrupted decision-making as these individuals come to grips with their new portfolios,” Skinner explains. “Since the beginning of 2019, the NOC has had four chief executives, three of which have been replaced as a result of factionalism, ineffectiveness in their roles or a combination of both. This challenge has been exacerbated by long-standing realities: heavy bureaucracy and unpredictable decision-making.”

Algeria’s current energy minister Mohamed Arkab has been in the role since February, when he was appointed as part of a broader cabinet reshuffle. Arkad had served as energy minister between April 2018 and June 2020, when he was replaced by Abdelmadjid Attar in another reshuffle ordered by president Abdelmadjid Tebboune.

There could be a further overhaul of personnel following the upcoming general elections. “Another reshuffle has the potential to once again delay the passage of the hydrocarbons law implementation texts,” Skinner warns.

Investors have also had difficulty buying and selling assets in Algeria. Italy’s Edison had to exclude its Algerian business from the sale of its upstream portfolio to Mediterranean-focused Energean, after authorities in Algiers blocked the deal. A few years earlier, US firm Occidental Petroleum was unable to transfer assets it was acquiring from Anadarko in Algeria to France’s Total for the same reason.

Investor dispute

At a time when Sonatrach is trying to promote Algeria’s upstream appeal, a now-former upstream partner, London-based developer Sunny Hill Energy, has presented quite a different picture of the country’s investment climate.

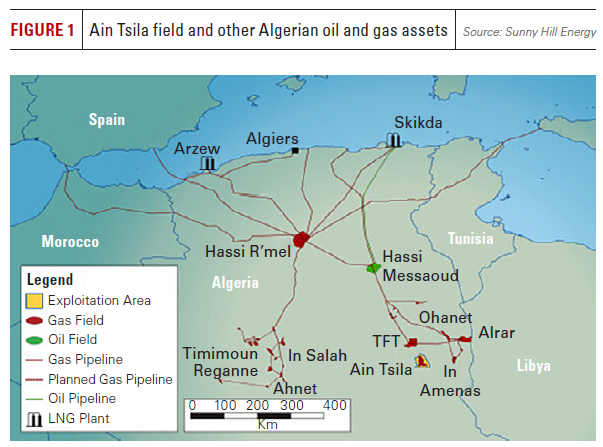

Sunny Hill accused the NOC in mid-April of seizing its share of the Ain Tsila gas and condensate field in eastern Algeria, warning it will seek “well in excess” of $1bn in damages.

The company has a 38.25% interest in the Ain Tsila field through its Petroceltic subsidiary. But Sonatrach has terminated the contractual interest without offering compensation, Sunny Hill said on April 15.

"Sonatrach has acted in an aggressive and irrational manner. Their expropriation of our interest without compensation is the type of action expected in Hugo Chavez's Venezuela and not from a country like Algeria that proclaims to respect the rule of law," Sunny Hill chairman Angelo Moskov said. "This unwarranted action will be highly damaging to the attempts by Algeria to attract foreign investment into the country."

In its own statement, Sonatrach confirmed on the same day that it had ended Sunny Hill’s upstream contract, citing the company’s failure to meet contractual obligations.

Sunny Hill entered Algeria after acquiring Petroceltic in 2015. A development plan for Ain Tsila approved in 2012 envisaged the launch of a gas processing plant in 2017, expected to produce 10mn m3 of gas, 17,000 barrels of LPG and 11,500 barrels of condensate/day. Petrofac won a contract in 2019 to build the plant by the end of 2022.

"Sonatrach will continue the development efforts of this project with the objective of bringing this deposit into production in November 2022," the Algerian company said.

The NOC did not respond to a request by NGW to comment. But its head Toufik Hakker told Bloomberg in April that project delays were the reason for the contract’s termination.

“We cannot tolerate delays in projects,” he told the news agency. “It is a strategic project for Algeria and Sonatrach.”

Speaking to NGW, Sunny Hill confirmed that its Petroceltic subsidiary had closed all operations and was exiting Algeria. The company said it could not disclose a breakdown of its claim at this time, but would do so when it filed the dispute with the International Chamber of Commerce.

Sunny Hill has invested “hundreds of millions of dollars” in the Ain Tsila site over the year, it said. The company has drilled and tested appraisal wells, including horizontal ones to improve production rates and recovery. Petrofac’s contract to build the plant was worth $1bn, awarded by Sunny Hill’s joint venture with Sonatrach. The plant is now 50% complete, the company said.

“Sunny Hill disagrees with the Sonatrach statement and refutes it entirely,” the company said. “Our company has never not complied with the PSC; however, any elaboration of this disagreement would not be proper at this time.”

The Covid-19 pandemic “naturally created delays,” the company noted, “but because of Sunny Hill’s commitment to an adaptable organisation, we overcame travel and country access difficulties by investing in remote working capabilities and onsite excellence programmes that minimised the schedule delays by Petrofac.”

Whether or not the case will tarnish Algeria’s image in investors’ eyes remains to be seen.

“It is too early to pass judgement on whether Sonatrach’s decision to cancel its JV with Sunny Hill Energy will sour already-qualified investor appetite. There is at this point no evidence to suggest it will have a negative knock-on impact,” Skinner says. “Sonatrach is adamant that its decision was 100% legal and appears to have come to the decision over delays which it blames on Sunny Hill Energy.”

He added that the case was not dissimilar to the cancellation of French firm Medex Petroleum’s contracts for the Bourarhat North and Erg Issouane fields in 2016. Sonatrach won the subsequent arbitration process.