Are LNG forecasts too optimistic? [NGW Magazine]

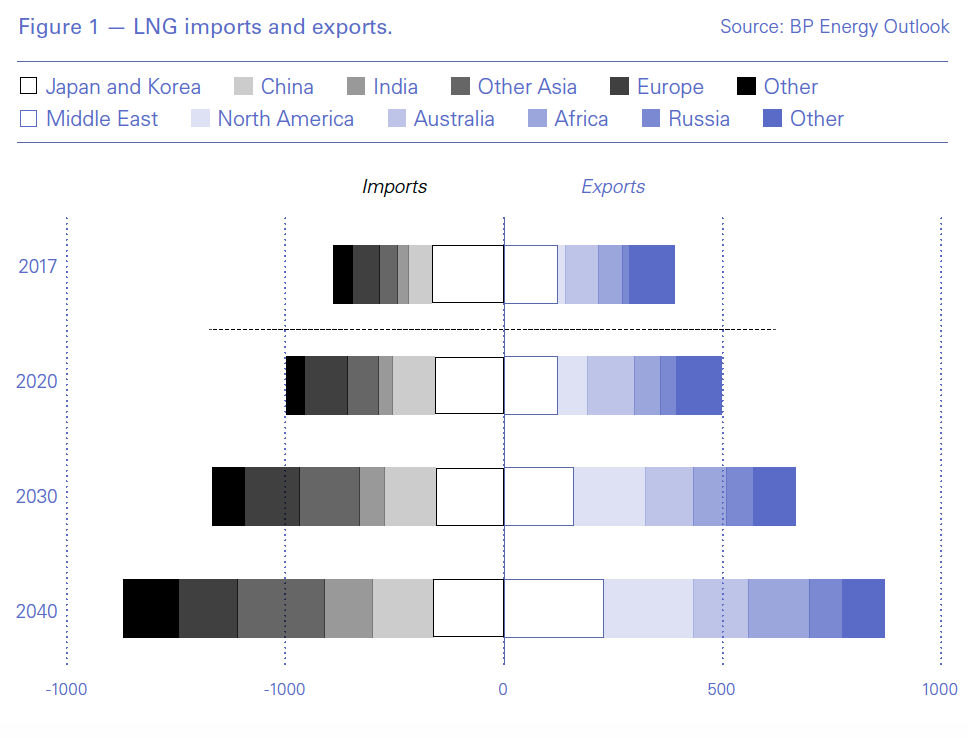

A plethora of LNG supply-demand forecasts and outlooks have been published, mostly forecasting that the demand growth trends observed during the last few years will continue to 2040, and even go further, according to BP Energy Outlook 2019 (Figure 1).

A special edition of Wall Street Journal in March states: “Expectations are for continuing strong growth,” with LNG demand projected to increase from 320mn mt in 2018 to 465mn mt/yr by the mid-2020s, and to reach more than 630mn mt/yr by the mid-2030s. Elsewhere it is stated that Asian LNG demand will quadruple by 2030.

In the light of developments and factors analysed in this article, these projections – and many other similar forecasts – are likely to prove too optimistic.

A number of recent events may impact this adversely. Trade wars, sanctions and other threats, as well as economic slowdown, are forcing major LNG importers in Asia to rethink their energy security and look inwards, reduce import dependence and maximise their domestic energy production.

This has come at a time of a substantial increase in new LNG supplies – about 70mn metric tons of new LNG supply is expected to hit the market over the next two years, with about 33mn mt coming in 2019.

But a lower increase in Chinese LNG demand – estimated to be about 8mn mt in 2019 in comparison with about 16mn mt in 2018 – and a reduction in Japanese LNG demand as nuclear plants return to service are creating a glut of LNG and are expected to keep prices low.

Environmental concerns are also multiplying, especially after the UN Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) issued October 2018 a Special Report on the ‘Impacts of global warming of 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways’. This drew attention to the fact that the world needs to cut carbon emissions urgently and drastically. Without action, the world is on track to reach a temperature increase of 3 °C by 2100, well in excess of the Paris agreement to limit the increase to 1.5 °C.

Environmental concerns are raising the pressure to cut all fossil fuel consumption, not just coal. Europe, for example, has put in place climate change targets that demand rapid decarbonisation: 32% renewables, 32.5% energy efficiency and 40% reduction in carbon emissions in comparison to 1990, all to be achieved by 2030, and net-zero emissions by 2050.

Gas also needs to deal decisively with methane leaks if it is to realise its potential as the cleanest of all fossil fuels.

Warnings

The energy transition is leading to structural changes in global energy markets. Oxford Institute of Energy Studies (OIES) has been warning in a number of recent incisive reports that “if Europe is to meet its longer term environmental targets, not only will gas’ place in the power sector be threatened post-2030 if it fails to develop a decarbonisation strategy, but its role in the heating and cooling sector will also come under threat.”

In addition, natural gas faces an ever more competitive environment with higher penetration of renewables – combined with energy storage and electricity and the impact of better energy efficiency. Carbon pricing mechanisms, such as Europe’s emissions trading scheme penalise fossil fuels – mostly coal initially but natural gas as well – and benefit renewables.

Another important factor is that in developing countries the future of natural gas, and invariably imported LNG, is dependent on prices. Researcher Jonathan Stern concluded in a 2017 OIES report that “many of the more optimistic demand forecasts are based on price assumptions that appear unrealistic relative to the levels that customers have been paying over the past decade.”

Taking the argument further, OIES director James Henderson said that “the disparity between the likely cost of new LNG projects and the affordable price of gas in many future growth markets will need to be closed by a focus on cost reduction by project developers, rather than by a hope that higher prices and rising demand will be sustainable at the same time.” Not unexpectedly, these OIES reports identified the main challenges to the future of natural gas as a transition fuel to be affordability and competitiveness, concluding: “The major challenge to the future of gas will be to ensure that it does not become unaffordable and/or uncompetitive, long before its emissions make it unburnable.”

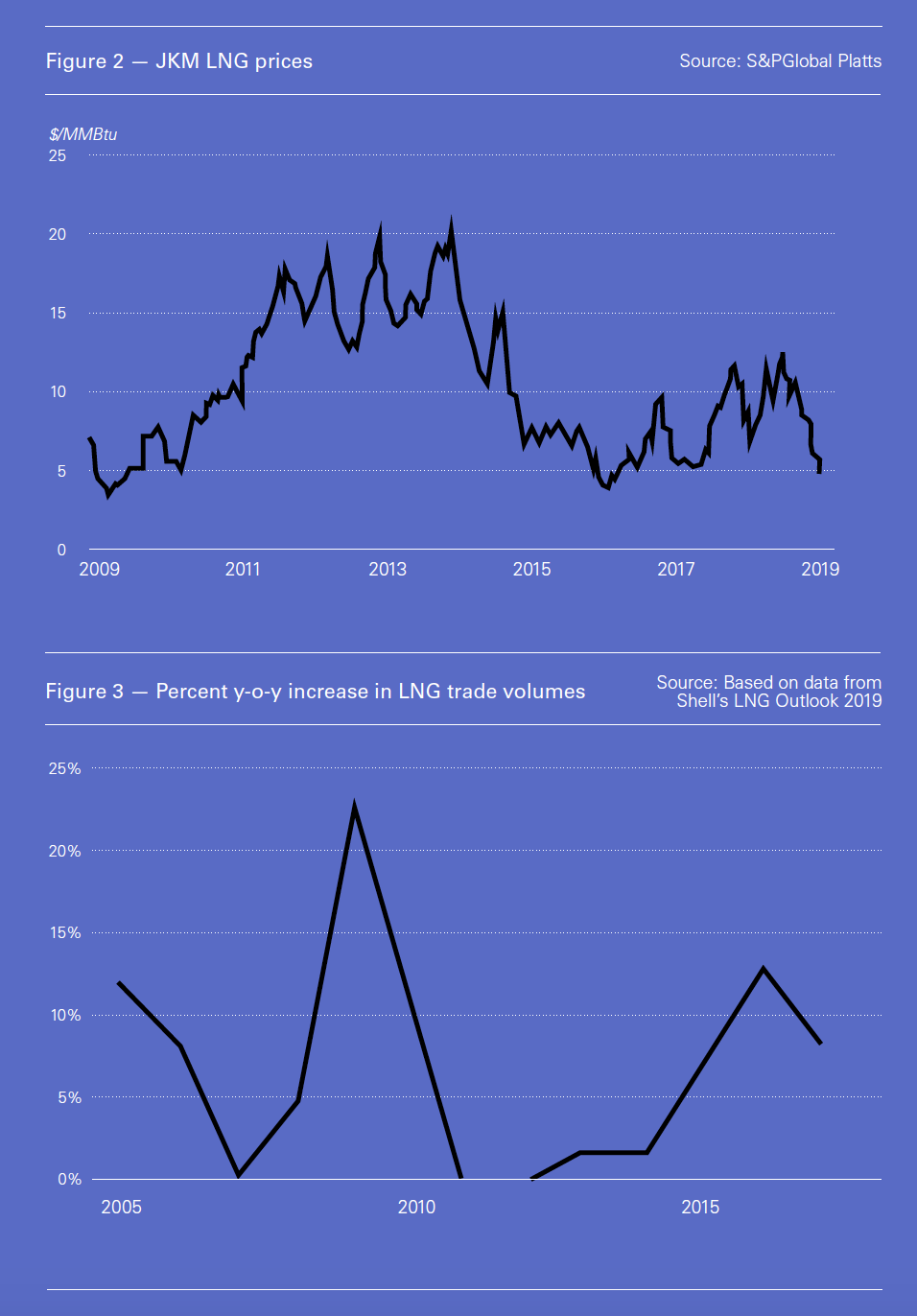

A comparison of LNG prices (Figure 2), percent y-o-y (year-on-year) increase in LNG trade volumes (Figure 3) and investment in liquefaction capacity (Figure 4) illustrates the point. There is close correlation. As expected, when LNG prices are low there is a reduction in commitments to final investment decisions.

The LNG market is entering such a period now, with prices trending quite low. As a result, many of the projects still to reach FID may be deferred, with mainly low-cost LNG projects materialising.

This time though this may not be a short-term trend. The factors shaping it have longer-term implications:

- Security of supply concerns mean that key LNG importing countries, such as China, India and Japan, are giving priority to increasing domestic energy production at the expense of imports – this may be an irreversible process, limiting future demand growth.

- The gas market is oversupplied, with many new discoveries and US shale gas coming into the market. This oversupply is likely to remain for a long time into the future if demand increase is limited.

- Increasing penetration of renewables combined with energy storage in the power sector, aided by carbon pricing, will be eventually impacting demand for natural gas in power generation.

- Coal demand in Asia is proving to be resilient.

- Inevitably these - and with coal and renewables prices becoming increasingly lower - will lead to lower gas prices in the longer-term.

These factors will impact future LNG demand and supply.

BP CEO Bob Dudley, speaking at the LNG19 conference in Shanghai in April, singled out trade wars as a key risk to global LNG markets. He said: "Countries need to have confidence in the security of their gas supplies.” Trade wars increase insecurity, encouraging countries to switch to domestic energy resources rather than rely on imports.

Optimistic forecasts

The high rates of increase in LNG demand experienced during the last two years were mostly due to factors that may not be repeated. Notable among these were the changes in China in 2017 in response to the clean air directive that caught the country unprepared and led to a massive increase in LNG imports, but also in prices.

Linear extrapolations based on LNG demand performance during the last few years are already proving to be too optimistic.

China has modified its policies to deal with the problems created in 2017 and 2018, but also concerns about security of energy supplies are being met by more coal, renewables, hydro, gas and nuclear output. This excludes countries with which it has ‘mutually beneficial co-operation and common energy security through coordination’, such as Russia. New gas pipelines, such as Power of Siberia, will reduce China’s dependence on LNG imports even further, although two state companies are buying into Novatek’s Arctic LNG 2, taking 20% together at time of press.

Japan is actually reducing LNG imports as it continues its return to nuclear power. In its 2030 energy plan it projects that LNG imports will fall from 88.5mn mt/yr in 2015 to 62mn mt/yr by 2030.

South Korea’s future LNG demand is also uncertain as it clings to its coal and nuclear power plants longer than originally anticipated, with the plan to increase the share of renewable power generation to 40% by 2040.

High energy prices are also a threat to India’s economic and energy security, forcing the country to maximise domestic energy resources such as coal and renewables. Coupled with infrastructure limitations, these concerns are limiting growth in LNG imports.

The share of natural gas in the region’s energy mix is less than 10%. Wider use of gas in Asia requires positive government policies to support it as a strategic fuel. At present this is lacking. Economic uncertainty is putting additional pressure on LNG prices and demand.

Middle East LNG demand has also declined dramatically – with Egypt actually turning into an exporter – and it is expected to be less than 4% of global demand for at least another eight years.

Many analysts expect Europe to absorb surplus LNG. While this may be the case in the short-term, it will not be so in the longer-term as EU’s 2030 climate change targets bite. These will eventually lead to a fall in gas demand.

What might happen

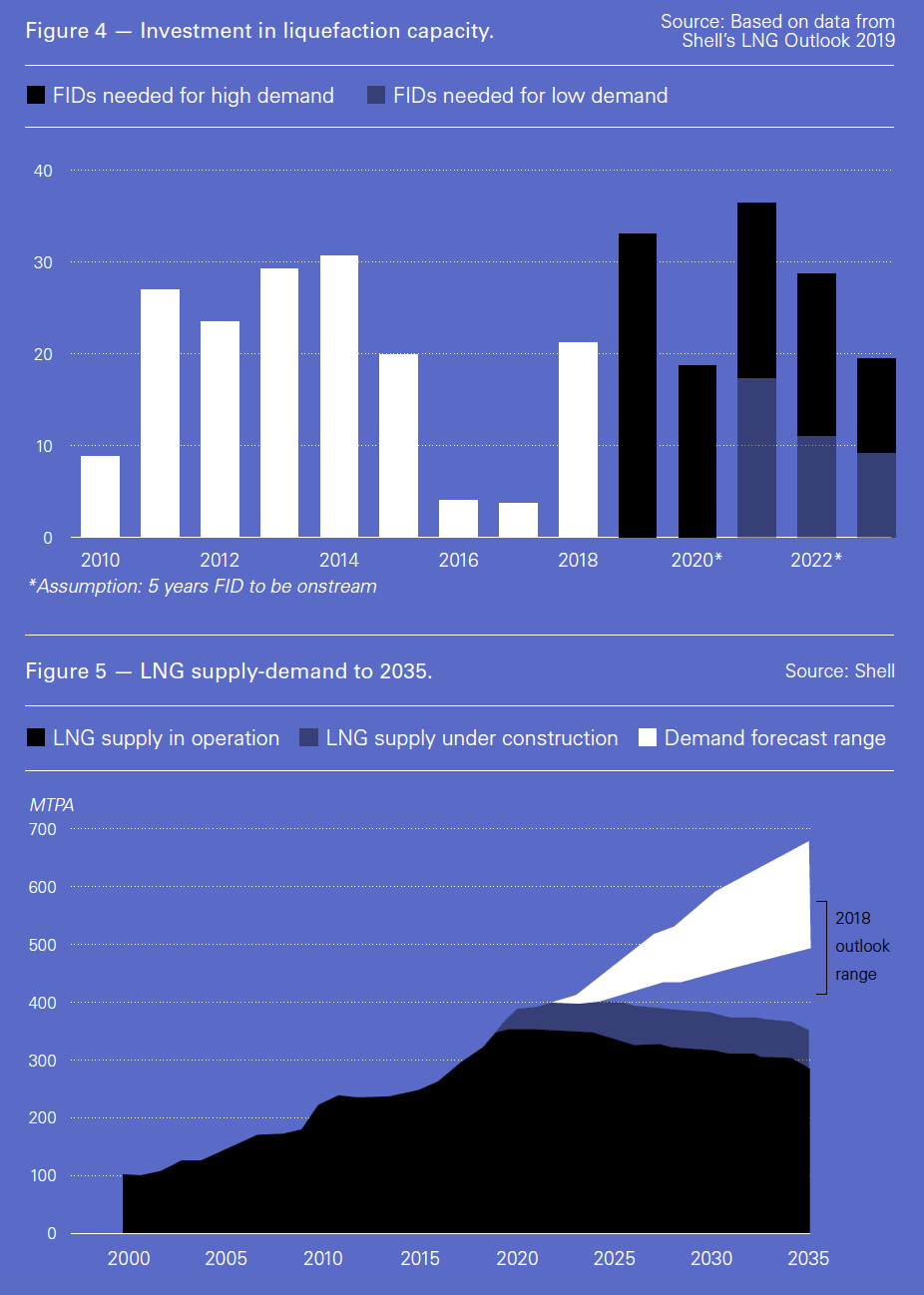

In its recent LNG Outlook (Figure 5) Shell produced a range of forecasts, with the high leading to about 680 mt by 2035 and the low to about 500 mt.

Given the potential impact of the factors described above, and low prices, future LNG demand is unlikely to reach the, optimistic, high estimate, but may be set back and more likely trend towards the lower end of the outlook range.

Projects with an estimated capacity of about 366mn mt/yr are already at an advanced planning stage with an expectation that they will be added by 2023, with more than 60mn mt/yr capacity expected to take FID in 2019. Of these, the US is expected to add around 215mn mt/yr, driven by increasing shale gas production. Clearly, what might happen as a result of lower demand and low prices is that many of these projects may not reach FID.

If future LNG demand is limited to the lower part of the outlook range in Figure 5, the additional supply required to meet demand by 2035 could be as low as 140mn mt/yr.

LNG investments over the next few years will need assured returns in the 2030s and even later – something that is becoming increasingly difficult to guarantee due to the uncertainties about longer-term prices. Would LNG producers be prepared to absorb such risk? It would be challenging for most.

Impact on new projects and LNG prices

Inevitably, reduced future demand will mean that prices will stay low for the longer term. With oil prices expected to range between $65-$70/barrel, forecasts at international conferences during the last six months show average gas prices to be converging to about $7.50/mn Btu in Asia and $6.50/mn Btu in Europe. Should these remain in the longer term, which is likely, they will pose increasing challenges to new LNG projects with high break-even costs.

Only low cost projects will reach FID (Figure 6). These are likely to include Qatar expansion, Arctic LNG and Mozambique Area 1. US LNG projects will succeed if the cost of feed gas is substantially less than the Henry Hub gas price – which is possible with associated gas.

Even though construction of large volumes of new capacity has already started, and many new projects are being lined up for FID, low prices and concerns about future demand are slowing down new approvals.

Only a few of the bigger companies are prepared to move ahead with new projects without long-term contracts. Most others will wait. The risk of going ahead without securing long-term customers has now increased – buyers want to benefit from low spot prices.

The turning point many expect in terms of a massive upturn in investment and new projects may have to wait, perhaps indefinitely.

There are justifiable warnings that over-reliance on Chinese demand growth – based on what happened during the last two years – has now become too risky. Notable among these voices is Woodside Petroleum’s CEO, Peter Coleman, who said that LNG producers must broaden their markets, develop new uses for gas and continue to push for a carbon tax globally to push out coal.

What should gas do

An obvious response to the changing global energy markets is for the gas market to:

- Bring prices down to as low as possible;

- Decarbonise;

- Combine upstream with downstream;

- Promote gas in industry.

But energy demand growth is now taking place mostly in Asia, where coal is still the dominant fuel force, with coal and renewables becoming cheaper.

Gas and LNG must remain competitive against both coal and renewables in order to maintain market share. And even then sanctions and trade war concerns threaten the gas market outlook in Asia.

A big effort to decarbonise and reduce carbon emissions and air pollution through carbon capture and storage and steam methane reformation would favour natural gas for at least the next 10 to 20 years. But security of supplies, costs and economic growth appear to take priority in Asia, while maintaining efforts to clean up air pollution in major cities. The last edition of NGW identified that ”in an about-turn to the Paris Agreement, China’s energy focus has now turned to domestic energy and security of supplies, with less concern about international pressure regarding its environmental policies.”

Shell is following a third route to deal with the oversupplied gas market – by moving into electricity to secure a market for its increasing gas business. Electricity, being the fastest growing form of energy, with a 4% increase in 2018 alone (GECO 2019), offers Shell the opportunity to combine upstream with downstream, through its new ‘Gas and New Energies’ business.

But nevertheless use of gas in power generation is meeting stiffer competition from renewables combined with storage. Where there is the best scope for future gas demand growth is probably in industry, especially for the provision of high temperature heat and in petrochemicals.

The next decade will be a period of profound change in energy markets. It certainly will not be business as usual. The gas and LNG sectors will need to be prepared for a prolonged period of change and projecting future demand growth for LNG based only on the past few years could lead to costly mistakes.