Asia’s biggest emitters soften COP26’s stance on coal [Gas in Transition]

Asia’s two largest carbon emitters – China and India – scored a major victory at the end of the UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow, as they forced through a compromise on coal consumption.

As envoys from nearly 200 nations gathered on November 13 to ratify a draft agreement that contained a commitment to phase out coal-fired power generation – although with no fixed timeline – China and India successfully lobbied to change the language to a “phase-down”.

The last-minute amendment to the Glasgow Climate Pact has created controversy around what is still arguably a progressive climate change agreement. COP26, after all, managed to deliver the world’s first climate deal to include plans to reduce consumption of the fossil fuel, while also ensuring countries agreed to return to the table next year with more aggressive emissions reduction targets.

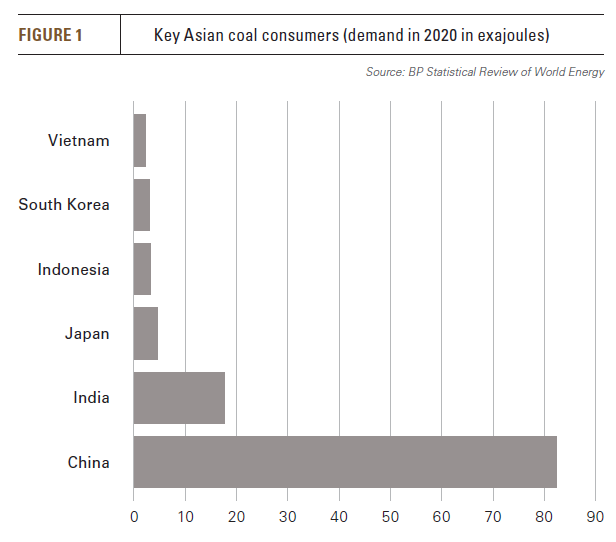

Given China and India’s heavy dependence on coal, with the fuel accounting for around 65% of China’s power generation mix and about 70% of India’s in 2020, both countries’ reluctance to sign a deal that specifies the end of coal use is hardly surprising.

Moreover, it makes a stronger case than ever that gas production and exports are the lesser evil as the global economy transitions away from fossil fuels.

Economy vs emissions

China’s economy has exploded over the last four decades, driven by a coal-fired industrial revolution that turned the country into the world’s factory.

But while China’s economic transition has been underpinned by coal use, that is not to say the Beijing government has been content with the status quo. Indeed, the last decade has seen billions invested in new natural gas import infrastructure, storage, pipeline networks and power generation.

China pledged last year to reach net zero by 2060 and aims to achieve this target through both the greater roll out of renewable energy capacity as well as higher consumption of gas.

The coal-to-gas transition has famously come with its own share of challenges, however, as supply lines and infrastructure have become strained by the rapid switchover, with gas shortages peaking in the 2017-2018 winter.

In the years that followed the government resumed its coal-to-gas push and began placing limits on domestic coal production in pursuit of its emission targets. This has backfired, however, with China witnessing one of its worst power shortages in decades since September.

Two thirds of the country’s provinces implemented power rationing in the wake of domestic coal shortages, government-mandated emissions restrictions, soaring domestic power demand and supply constraints on the international gas market.

Beijing was forced to ease its curbs on coal production in order to get a handle on the crisis and, with miners rapidly spinning up operations, the country produced a record 12.05mn metric tons of the fuel on November 11, according to the official Xinhua news agency.

It is easy to see, then, why China is reluctant to lose one of its tools in managing domestic energy security. The country is striving to reduce coal consumption, even though its economy has been built on the fuel.

India, meanwhile, finds itself in an even more awkward spot.

Development agendas

While China announced its target last year, Indian prime minister Narendra Modi took to the stage on November 2 to pledge that his country would reach net zero emissions by 2070. While still short of COP26’s goal of net zero by 2050, Modi’s announcement was the first time the South Asian giant had set an emissions target.

However, as the conference drew to a close India found itself an unlikely ally of China, with New Delhi also pushing back against the Glasgow Climate Pact’s wording on coal-fired power generation.

Indian Environment Minister Bhupender Yadav argued that developing countries had a right to “their fair share of the global carbon budget and are entitled to the responsible use of fossil fuels”.

He went on to ask: “How can anyone expect developing countries to make promises about phasing out coal and subsidies for fossil fuels when those countries have still to deal with their development agendas?”

Given that New Delhi’s 2070 target is behind even China’s it is unsurprising that the country wanted to avoid a target, no matter how vague, of phasing out coal-fired power. After all, Modi’s administration has spearheaded economic reforms in recent years that aim to boost manufacturing’s share of GDP from around 16% at present to 25% by 2025. Such an uptick will require stable power supplies.

Interestingly, and somewhat unexpectedly, both China and India’s refusal to accept more definitive language around bringing coal use to end should be seen as a win for gas.

Unexpected winner

The deal-making struggles at COP26 serve to highlight the coal dependence of Asia’s two largest emitters while also underscoring the importance of gas as a transition fuel.

Australia’s announcement just days before the start of COP26 that its new 2050 net zero target would not require curbs on gas or coal production raised some eyebrows. Canberra said at the time that a “technology not taxes” approach would deliver the necessary emission cuts.

It was a message Australian prime minister Scott Morrison happily doubled down upon during the first day of the conference. While announcing that Australia would double climate funding support for Southeast Asia to A$2bn, Morrison said: “Driving down the cost of technology and enabling it to be adopted at scale is at the core of the Australian way to reach our target to reach net-zero emissions by 2050 that we are committing to at this COP26.”

Australia is the world’s largest exporter of LNG and the government has faced growing pressure both at home and abroad to tackle the full lifecycle emissions of gas exports.

Beijing and New Delhi’s refusal to phase out coal-fired power, however, makes a compelling argument that gas is needed now more than ever to help Asia’s economies wean themselves off dirtier alternatives.