Australian LNG export levels under threat [Gas in Transition]

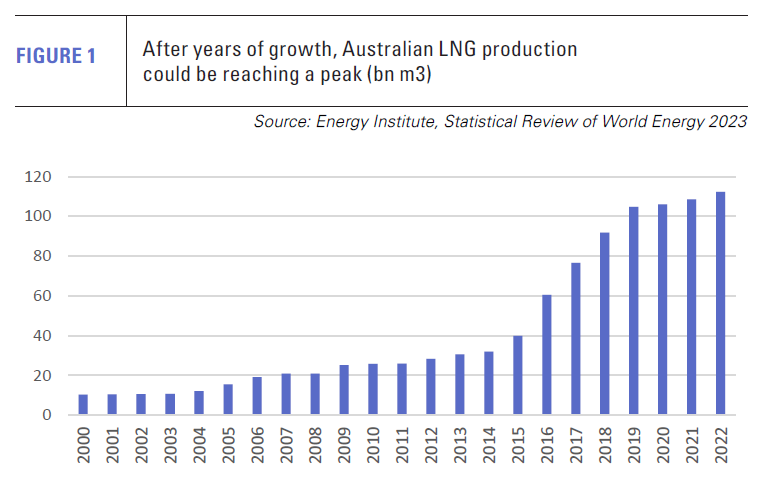

Australia has a total LNG production capacity of 88.6mn tonnes/year and shipped a record 81.4mn mt last year, accounting for 21% of global LNG exports (see figure 1). Most production came from Western Australia (49mn t), followed by Queensland (24.1mn t) and the Northern Territory (9.2mn t).

As a result, the sector is an important part of the economy, generating A$90.4bn ($62.3bn) in export revenues in 2022, up 82% on the previous year according to consultants EnergyQuest, as a result of high global prices.

Emissions policies getting tougher

However, the Labor government of Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, which came to power in May 2022, has made a legal commitment to achieve net zero by 2050 and, under a deal with the Green Party, on July 1, pledged to cut greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 43% from 2005 levels by 2030. Australia’s per capita GHG emissions are amongst the highest in the world.

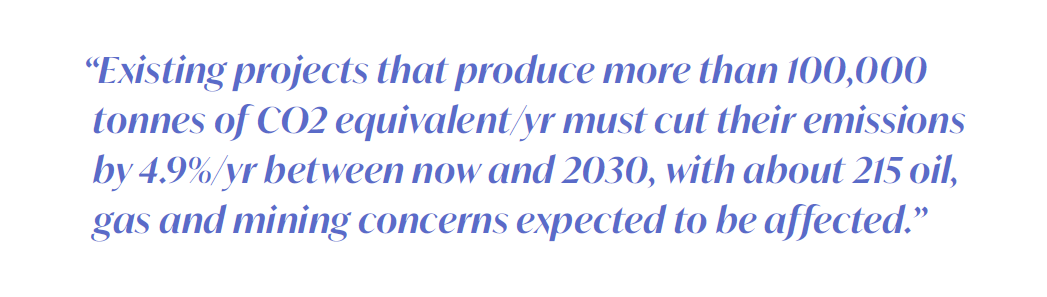

Existing projects that produce more than 100,000 tonnes of CO2 equivalent/yr must cut their emissions by 4.9%/yr between now and 2030, with about 215 oil, gas and mining concerns expected to be affected. Under the agreement, ministers must also review any planned projects that will raise total emissions.

In addition, the new legislation requires new gas fields to abate or offset all reservoir CO2 emissions within Australia. As a result, most will have to incorporate carbon capture and storage (CCS) to be sanctioned, driving up project costs. This could hit LNG producers in the near future as new fields need to be developed to replace mature fields that are becoming exhausted.

Queensland’s coal seam gas (CSG)-supplied LNG projects have a particular challenge in cutting emissions. Although it is difficult to accurately measure methane emissions, CSG projects can suffer from high rates of leakage because of the much higher number of wells needed to produce the gas. While LNG plants can be supplied with natural gas from conventional reservoirs with perhaps just ten wells, CSG projects typically require thousands of wells.

The LNG sector also faces higher costs after the government announced in May that producers would have to start paying the Petroleum Resource Rent Tax (PRRT). Most schemes were not previously expected to pay significant amounts of PRRT until the 2030s. At the same time, Australian banks are coming under increasing pressure to join their counterparts in other parts of the industrialised world to restrict financing for coal, oil and gas projects.

Domestic supply diversion

The LNG industry could also be affected by gas supplies being diverted for domestic consumption. Under the Australian Domestic Gas Security Mechanism, introduced in 2017, Canberra is allowed to restrict LNG exports to ensure domestic gas supply. The mechanism has never been used, but the new government has expressed a willingness to implement it now.

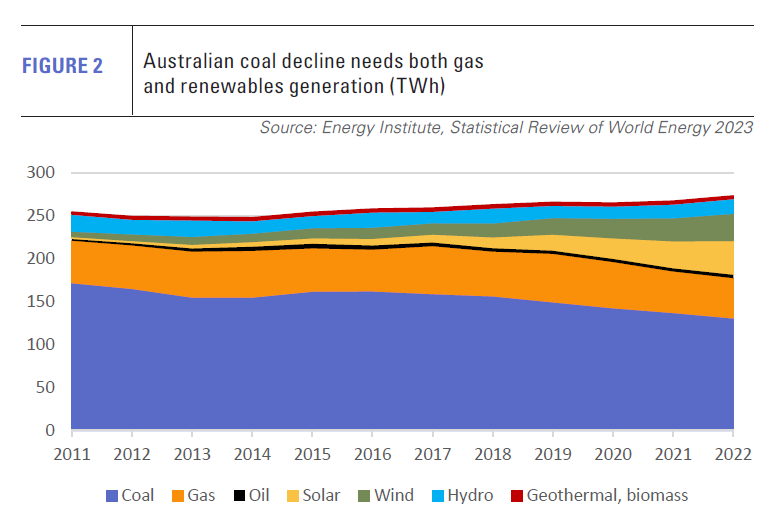

Some fields that supply Australian consumers are nearing the end of their productive lives and new sources of supply are needed, particularly as the government is attempting to reduce the proportion of coal in the generation mix faster than renewables are currently filling the shortfall (see figure 2).

Some fields that supply Australian consumers are nearing the end of their productive lives and new sources of supply are needed, particularly as the government is attempting to reduce the proportion of coal in the generation mix faster than renewables are currently filling the shortfall (see figure 2).

The mechanism would have a particular impact on Queensland’s CSG-supplied LNG projects, as most domestic demand is located on the east coast.

In a January report, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission said the east coast would face a shortfall of 28bn ft3 of gas this year, if LNG plants utilise all of their production capacity. Then, in March, the Australian Energy Market Operator said that there was a risk of gas shortages every winter from 2023-26 in the event of extreme weather. At the same time, it could be more difficult to develop new gas reserves in the east because of opposition from some state governments.

On July 10, the government extended the existing A$12 (US$7.98)/GJ cap on east coast wholesale gas prices, although this is not expected to have a significant impact on prices.

Samantha McCulloch, the CEO of the Australia Petroleum Production & Exploration Association said in a statement: “Investment in new gas supply is now urgently needed to avoid shortages. The government has taken the reins of the east coast gas market and with this comes the responsibility for ensuring sufficient supply and investment certainty.”

Legal challenges mount

In the face of Canberra’s new policies, there are likely to be lengthy legal battles over new gas projects. In July, the Western Australia Environment Protection Authority (EPA) rejected appeals by environmental organisations against its decision to recommend that oil firm Woodside be permitted to continue operating its North West Shelf LNG plant on the Burrup Peninsula in Western Australia until 2070. The appeal argued that emissions released during consumption had not been assessed.

The EPA had already recommended the extension be sanctioned, providing Woodside cut production emissions by two thirds, including by buying carbon credits. It directed Woodside to “consider reasonable means” to cut emissions on the project, a rather vague wording.

The EPA also recommended cutting nitrogen oxide and volatile organic compounds by a minimum of 40% by 2030 to reduce the damage inflicted on 50,000 year old Murujuga indigenous rock art.

Woodside itself estimates that the project could release 4bn t of CO2 equivalent. The decision increases the likelihood that the extension will be approved, although federal approval is still required. Nonetheless, other oil and gas projects are likely to encounter emissions-based legal challenges.

New investment starts to emerge

Canberra hopes that its strategy will encourage the oil and gas sector to cut emissions wherever possible and some new investment in this direction has already been announced. For instance, TotalEnergies and Petronas offshoot Gentari announced in July that they would develop a solar project in Queensland to provide low emissions power to the Gladstone LNG project.

The 100-MW Pleasant Hills solar project will supply electricity to the Roma CSG field’s production and processing facilities. Most power used in the area at present comes from coal-fired plants.

Japanese buyer disquiet rises

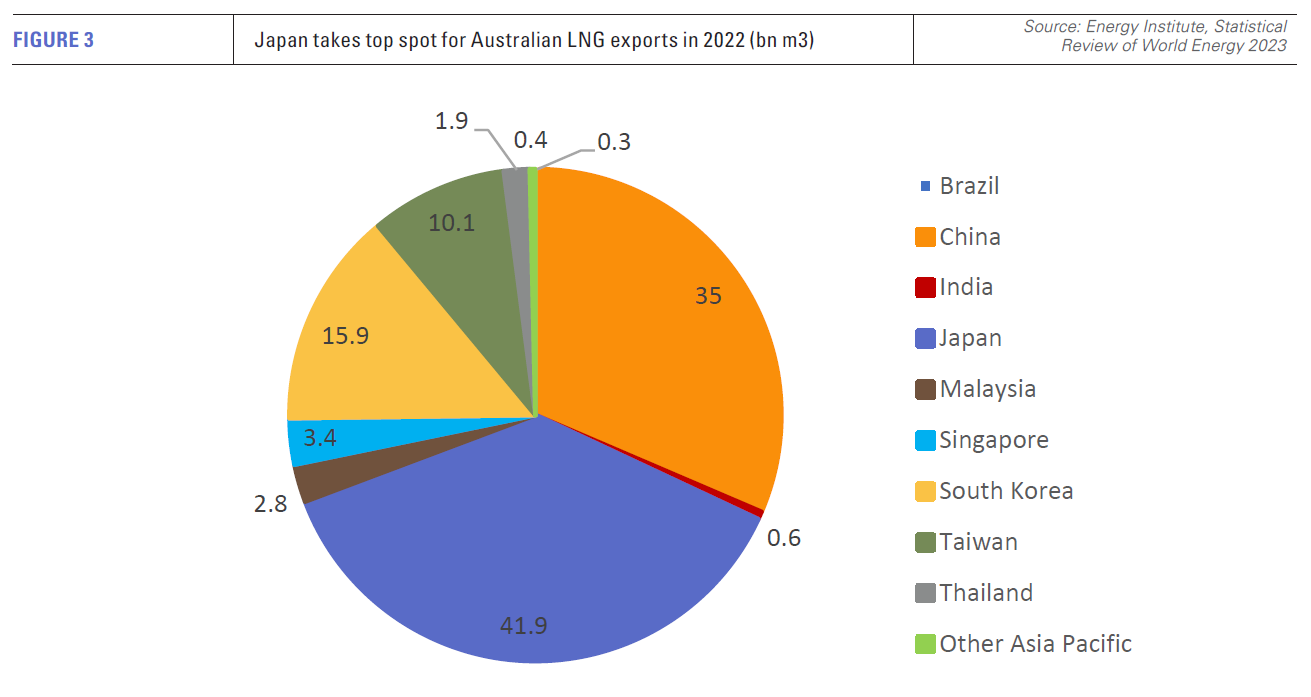

Given the complex evolving policy environment, Japanese investors in Australian LNG projects and LNG importers are concerned about Australia’s long-term reliability as a source of supply. Japan was the biggest market for Australian LNG last year, importing 31.2mn t, equivalent to 43% of total Japanese LNG imports, compared with China taking 22.6mn t (see figure 3).

The Japanese government is particularly concerned about the impact on projects for which final investment decisions have already been taken, and has asked Canberra to provide more information on whether CCS and ACCUs will actually enable project development. At the end of March, Inpex CEO Takayuki Ueda said that Australia’s investment climate appeared to be deteriorating and suggested the country was “quietly quitting” the LNG sector.

Japan may be especially annoyed by Australia’s new stance because some Japanese customers chose not to renew long-term LNG contracts with Qatar that expired in 2021 and 2022. Japan has 24mn t/yr of long term contracts with Australia, of which 8mn t/yr will expire by 2029. Some may switch to Middle Eastern suppliers that look less likely to try to cut LNG industry emissions in the same way as Canberra.

Japan’s Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry Yasutoshi Nishimura said that bilateral talks were ongoing “regarding measures for protecting Japanese investors and ensuring a stable supply of LNG, in order to find a mutually acceptable solution”. Australia’s Minister for Climate Change and Energy, Chris Bowen, is to visit Japan in August in response to Japanese disquiet.

CCS projects prove challenging

The CCS element of the Gorgon LNG scheme has already stored 8mn t under Barrow Island in Western Australia and US major Chevron expects the figure to reach more than 100mn t over the lifetime of the project. However, the company admitted in May that the project, which was late coming online, is running at just a third of its planned capacity.

Carbon from the Santos-sanctioned Barossa gas project in the Northern Territory, which is to supply the Darwin LNG project, is to be stored in depleted reservoirs on the Bayu-Undan oil and gas project in the Timor Sea. First production is due in 2025, but the CCS element of the project will not begin to operate until 2027 at the earliest. As a result, Australian Carbon Credit Units (ACCUs) may be needed to cover the period between the two elements starting up.