Banks bolster support for oil and gas [Global Gas Perspectives]

Barclays has become the latest major international lender to backtrack on oil and gas. Its CEO CS Venkatakrishnan told Bloomberg on June 25 that banks could not go “cold turkey” on the oil and gas industry without creating energy security risks. He said that calls for banks to abandon oil and gas are unrealistic. The end goal – net zero by 2050 – is not in question. What is in question is how quickly investment in oil and gas should be scaled back. That’s remarkably frank coming from a bank that only in February announced that it would cease funding new “upstream oil and gas expansion projects,” after bowing to pressure from climate change activists.

Venkatakrishnan said: “We are very much moving away from coal to oil, oil to gas, gas to clean energy and the reality is that for quite some time fossil fuels will be with us, especially natural gas;” they are still required for many essential activities. The transition path is long and “the world economy cannot go cold turkey on this tomorrow.” Transition needs to be orderly. Global energy demand needs to be met while renewable energy is scaled.

Barclays is not the only lender to do so. Other major lenders, including Citigroup, JPMorgan Chase (JPMC) and Goldman Sachs, have cautioned that a “complete withdrawal from oil and gas comes with unacceptable energy security risks.” This is despite the immense pressure they are under from climate change activists to withdraw such support.

It will be interesting to see whether other European banks will follow Barclays. So far, most have been tightening their conditions for lending to the oil and gas industry in line with activist calls, but six banks, led by Deutsche Bank, have not. This is not the case in the US.

In fact, JPMC has called for a reality check on the expectations for a quick shift from oil and gas to alternatives, adding that inflation, interest rates and wars may delay energy transition even further. JPMC said changing the world’s energy system “is a process that should be measured in decades, or generations, not years.” The company’s CEO Jamie Dimon added that quitting oil and gas is “enormously naïve.”

David Solomon, the CEO of Goldman Sachs, said as much in response to activist pressure, stating that without energy security society will not function. “Traditional energy [fossil fuel] companies are hugely important to the global economy” and “we are all going to continue to finance traditional companies for a long time.”

In another development, BlackRock – the world’s largest money manager – scaled back participation in the Climate Action 100+ group, an investor-led initiative to ensure the world's largest corporate greenhouse gas emitters take appropriate action on climate change. JPMC pulled out completely. This means that none of the world’s top five money managers fully back the group, weakening its effectiveness.

Stung by accusations that it is “boycotting” oil and gas companies, BlackRock took the unusual step of “setting the record straight.” The company made it clear that it does not dictate how its clients invest and defended its continued investment both in fossil fuels and clean energy. In his annual letter in 2023, CEO Larry Fink stressed the importance of oil and gas in meeting global energy demands.

Interestingly, even where Western banks pull out of oil and gas projects as a result of activist pressure, often Chinese lenders step in.

The world’s top provider of fossil fuel financing in 2023 was JPMC, followed by Japan’s Mizuho and Bank of America.

Most banks have targets to move away from fossil fuels, on the way to net zero, but almost all major lenders are of the view that oil and gas will be around “for quite some time” and back an orderly transition.

Energy transition will be a long process

Investments in renewables and the growth in low-carbon electricity generation are thriving, increasing exponentially. But, so far renewable energy sources have been unable to cope with rising energy demand on their own. As the latest Energy Institute (EI) report from the 2023 ‘Statistical Review of World Energy’ shows, global primary energy demand increased by 2% in 2023, higher than the 1.4% average during the previous ten years. Even though renewables provided 44% of this growth, fossil fuels provided the remainder.

The contrast between developed and developing countries is stark. In 2023, primary energy demand actually declined by more than 1.5% in OECD countries, but increased by a staggering 4.3% in non-OECD countries, with fossil fuels providing close to 80% of this growth.

In fact, fossil fuels still provide about 84.5% of primary energy demand in non-OECD countries despite the rapid growth in renewables. Leaving aside nuclear and hydro, solar and wind provided less than 6.6% of primary energy demand in non-OECD countries, even after growing by 18% in 2023.

Evidently, during the energy transition oil and gas will continue to be important to the global energy mix, especially as the penetration of renewables in sectors other than electricity is very low, and more so in Asia and Africa. Globally, electricity demand grew by 2.5% in 2023, much the same as in 2022, and comprised 17.4% of global primary energy demand, only marginally up on the 17.3% in 2022. At this rate, energy transition will be a long-drawn process.

BP’s World Energy Outlook, released in July, arrived at a similar conclusion, that low-carbon energy sources are not growing quickly enough to keep up with global energy demand.

Maintaining oil and gas reserves and production to support this demand is critical to global energy security. The oil and gas majors have been making this point for a while, but it is important to now see international banks and lenders coming to a similar conclusion.

Competing interests during energy transition

Citigroup put its finger on the challenges faced by major banks and lenders as they navigate these competing interests. As Ilan Jacobs, a director at Citigroup, said: “ultimately, these competing interests that you have to manage are stuff that we have to work on with our clients very closely.”

In an attempt to “name and shame,” groups like Oil Change International (OCI) publish data to draw attention to the fact that banks remain financially committed to oil and gas despite energy transition. According to OCI, “the world’s 60 largest banks have invested $6.9 trillion in the oil and gas industry since the Paris Agreement was signed in 2016.” It also states that “financing for LNG increased in 2023, hitting $120.9bn.” From OCI’s perspective, this is seen as bad news. But the reality is that demand for natural gas is rising, with the Gas Exporting Countries Forum (GECF) forecasting that global natural gas demand will rise by 34% by 2050. LNG demand is rising even faster, because Europe has been switching from pipelines to LNG, as has the rest of the world.

Global energy demand continues to grow, driven by higher consumption in non-OECD countries, and while this is happening, as EI’s Statistical Review has shown, the world will need all the energy it can get.

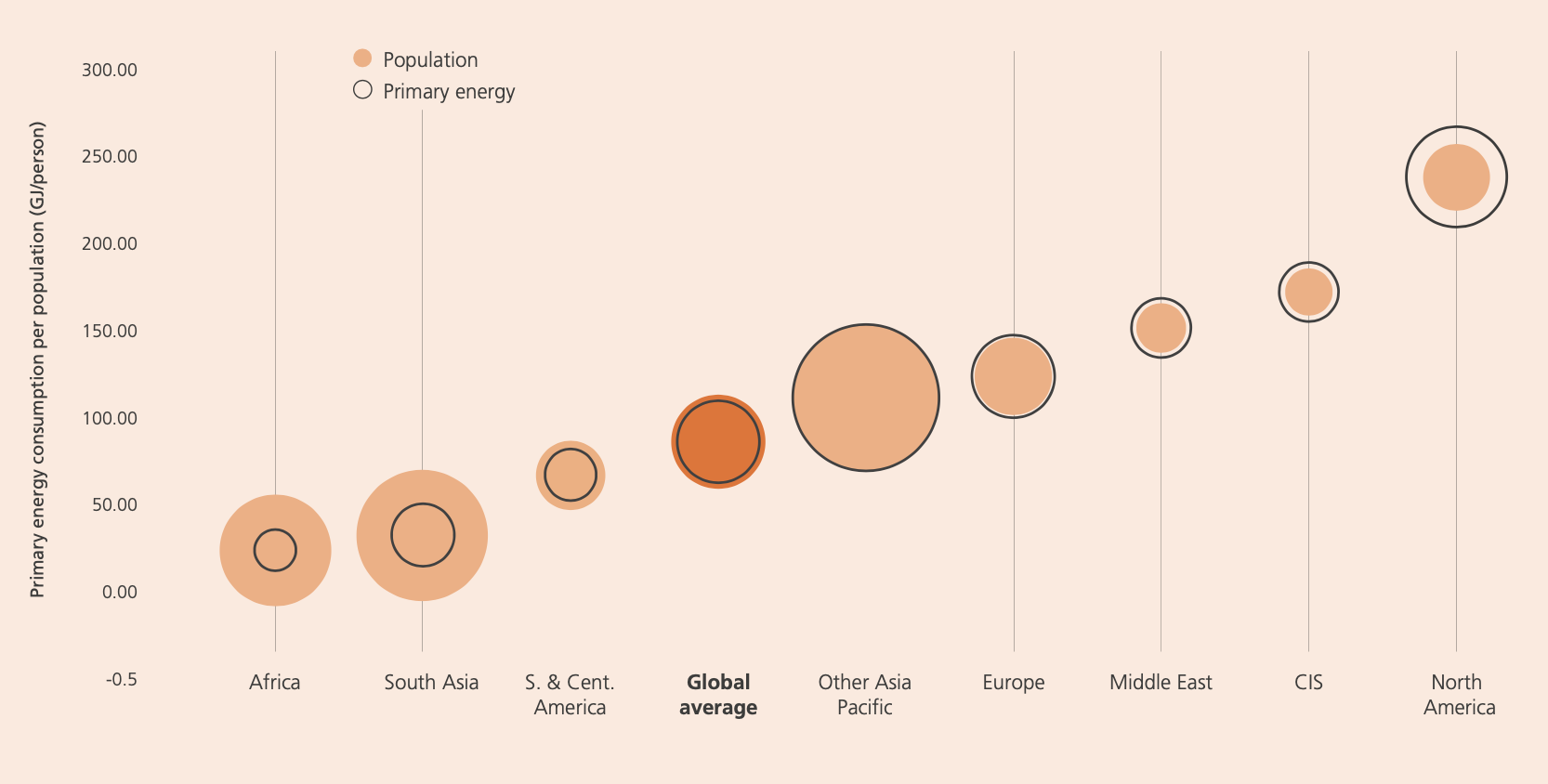

The Review states that in 2023 the average amount of energy consumed per person in Africa, South Asia, and Southern & Central America, comprising 48% of the world’s population, was 30 GJ, about 27% the global average of 110 GJ/person (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Energy consumption per person per part of the world, 2023

Source: Energy Institute 2024 Statistical Review of World Energy

The populations of these countries will carry on increasing and by 2050 they are expected to comprise 61% of the world's population. They also aspire to better living standards, which means their energy consumption will inevitably get closer to the global average. Even if their energy use only doubles to 60 GJ per person, this would lead to a global energy use increase by 35% by 2050.

These factors alone explain why global energy demand will carry on growing, dominated by non-OECD countries, with renewables alone not being able to provide it.

On that basis, the notion that oil and gas demand would peak in 2030, as the International Energy Agency (IEA) claims, looks unlikely. Goldman Sachs and others expect oil demand to keep growing to the middle of the next decade and then plateau, rather than decline sharply. To a large extent, the impact of increasing EV penetration on oil demand is expected to be offset by petrochemical demand growth.

Such factors are more often than not glossed over in climate change debates, but they will not go away – it’s reality. Even the EI, a strong advocate of transition to clean energy, recognises that this will lead to “significant energy demand growth in the future.” This poses the biggest challenge to the arguments of climate change activists.

These are also the reasons why oil and gas companies, such as Shell and BP, and now banks, have been backtracking on energy transition commitments and are increasing their oil and gas investments.

Impact on energy investment

Undoubtedly though, pressure on banks and lenders by climate change activists in Europe and in the US to stop financing oil and gas projects will carry on increasing. But almost all major lenders are making commitments to actively support energy transition and more sustainable energy sources, rather than simply divest from oil and gas.

In response, increasingly oil and gas companies are focusing on capital discipline, prioritising high-return low-carbon projects. So far, they “have not seen a material impact to the near-to-medium-term funding in terms of access to capital and cost of capital.” But S&P Global warns that “funding availability for independent oil producers in North America and Europe could face intensified pressures after 2030.”

In a report published in June, the IEA asked the question “Who is investing in energy around the world, and who is financing it?”

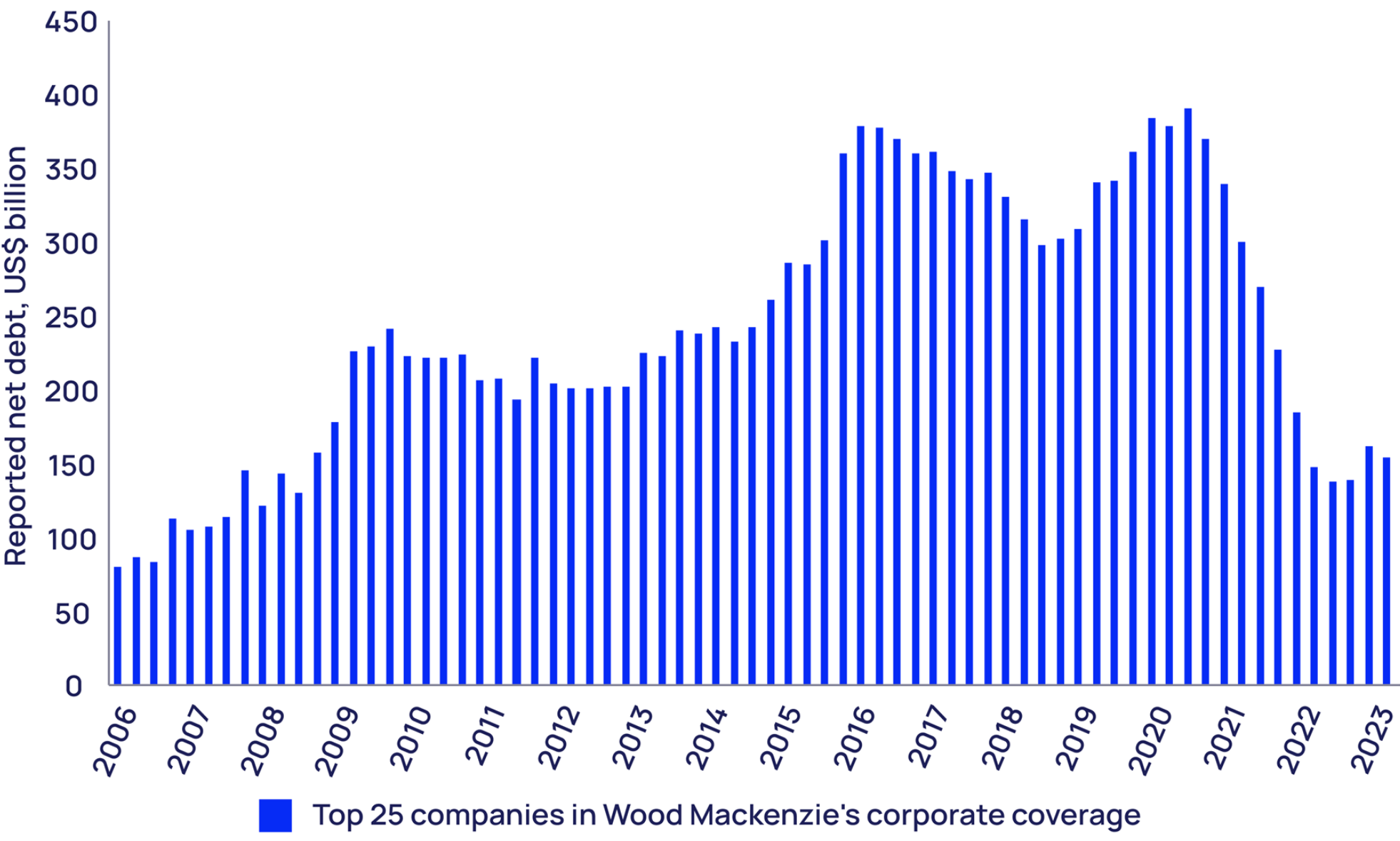

Not surprisingly, its overall conclusion is that “investments in fossil fuel supply see larger equity stakes, while debt financing is important for the clean energy sector.” Higher energy prices since 2022 have helped oil and gas companies reduce their debt to levels not seen since 2008 (see figure 2) and “finance investments primarily through retained earnings,” as well as increase buybacks.

Figure 2: Oil and gas company debt, 2006 to 2023

Source: Wood Mackenzie

As Wood Mackenzie points out: “the oil and gas sector has less to fear in a tighter interest-rate environment,” in comparison to the renewables sector where the cost of investing is high.

National oil companies (NOCs) are in an even better position. They generate sufficient income from upstream assets to cover their capital requirements, and, as a result, they rely less on debt spending.

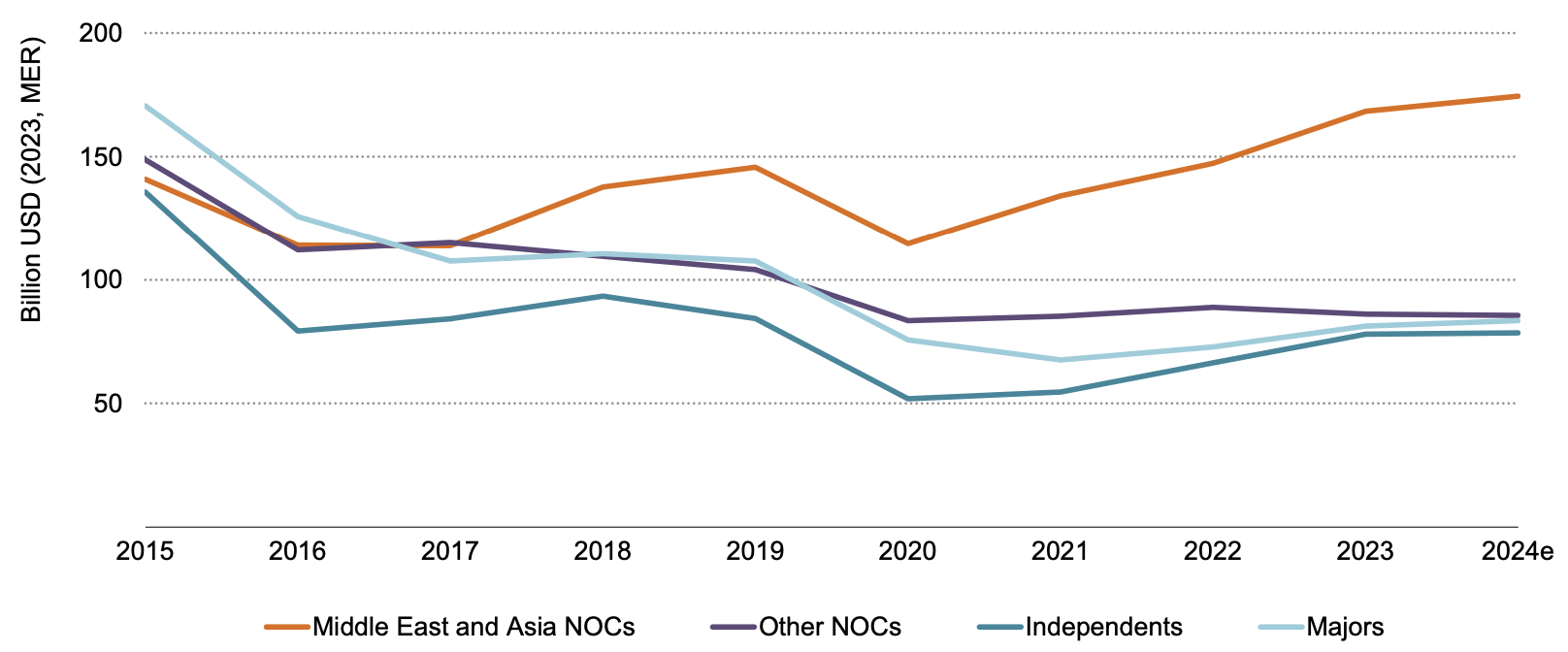

According to EAC’s World Energy Investment 2024 report, “upstream oil and gas investment increased globally by 9% in 2023 and looks set for a 7% rise in 2024, with most increases coming from Middle East and Asian NOCs.” (Figure 3) Overall, demonstrating this renewed confidence, upstream investments are back to levels seen between 2016 to 2019, prior to the crisis.

Figure 3: Upstream capital investment, 2015 to 2024e

Source: IEA World Energy Investment 2024

However, S&P Global Ratings is warning that “increasingly restrictive financed emission targets due to lender policies, regulatory policies and net-zero alliance memberships” will be impacting future funding. On the other hand, Middle East and Asia NOC spending carries on increasing, compensating for this. Overall, the oil and gas industry should continue upholding capital discipline, prioritising lower-carbon projects, especially in natural gas where future demand is on the increase.