Bleak future for Bolivian gas [NGW Magazine]

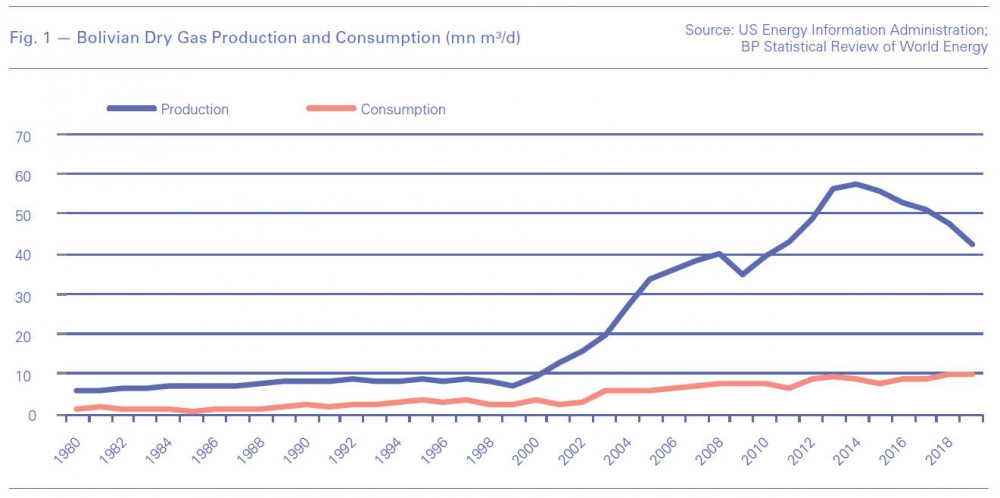

State-owned Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales Bolivianos (YPFB) did a commendable job of increasing the country’s marketed gas production by almost three-fourths to 58mn m³/d in the eight years between nationalisation in 2006 and 2014 (Figure 1). But the former government of Evo Morales was accused of “milking the cow but feeding it no grass” as YPFB has focused on boosting production to the detriment of exploration, for which it has neither the necessary financial muscle nor technical expertise.

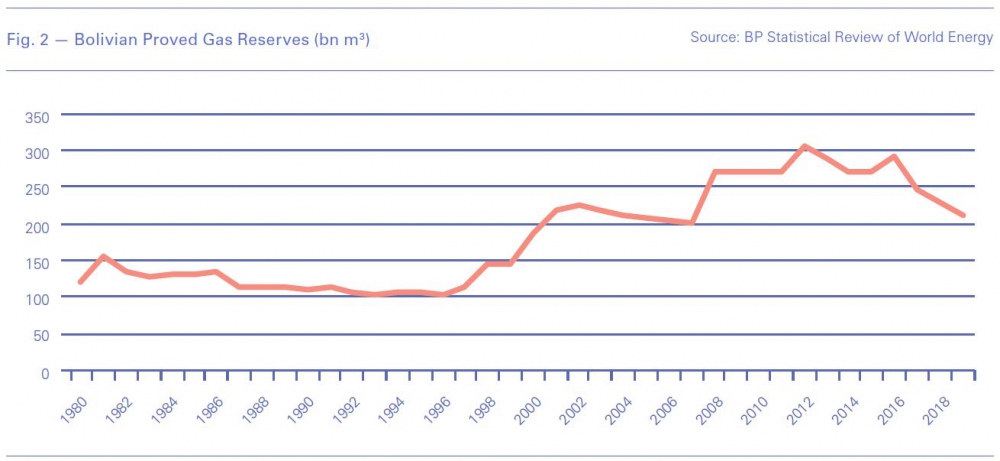

As a result, after firming up reserves in formations previously discovered by international oil companies, Bolivia’s proved gas reserves have been in free-fall since 2012, declining by almost a third to 213bn m³ in 2019 (Figure 2). This in turn has contributed to Bolivian marketed gas production dropping by over a quarter between 2014 and 2019, to 42mn m³/d.

To his credit, Morales saw the writing on the wall, and in the middle of the last decade he allowed the energy ministry to loosen contract terms for foreign oil companies. This was part of his attempt to re-energise gas exploration in the country. Bolivia was fortunate in that most of the international companies that were present – including Spanish Repsol, Anglo-Dutch Shell and French Total – remained after nationalisation, and simply adjusted themselves to the newly less profitable contracts for current production.

But Bolivia’s efforts are being hampered by declining foreign markets, compounded by political turmoil since the disputed presidential election last October and then the economic fallout from the global Covid-19 pandemic. The country’s total gas production collapsed to a mere 28mn m³/d in April, before rebounding somewhat to 35mn m³/d in May, based on data from the national institute of statistics. Prices for Bolivian gas are down over two-thirds, reflecting the collapse in oil prices.

Sales to Argentina and Brazil, the two export markets for Bolivian gas, are increasingly under threat from rising domestic gas production – shale gas from the Vaca Muerta and conventional gas from sub-salt fields, respectively – and relatively and increasingly cheap LNG. When the Bolivian government signed long-term gas export contracts with Brazil in 1999 and Argentina in 2006 and linked their landlocked country to its neighbours with pipelines, gas was a relatively scarce and expensive fuel. Argentina is now itself an LNG exporter.

At the same time, Bolivia’s efforts to open new export markets for its gas were moving slowly even before recent political events stalled them. The interim government ruling the country since last November, led by Jeanine Anez, lacks the legitimacy and political support to negotiate the necessary deals. Despite promising new national elections within three months, her government has postponed them three times, leading to mass street demonstrations and blockades across the Andean country.

Bolivia has had talks with Paraguay to build a gas pipeline between the two countries, and also with Argentina and Peru to export gas to international markets using the liquefaction plants in their countries. La Paz had hoped to build an LNG plant on the northern coast of Chile, but this was blocked by an October 2018 ruling by the UN’s International Court of Justice against its longstanding claim for sovereign access through its western neighbour. Bolivia lost its coastal provinces in a war with Chile in the late 19th century.

Established markets

Since peaking at a combined 45mn m³/d in 2014, according to BP Statistical Review of World Energy data, by 2019 Bolivia’s gas exports to Argentina had declined by 9% to 13mn m³/d and to Brazil by a whopping 42% to 15mn m³/d. These declines are reflected by changes in contracted gas volumes from Bolivia being renegotiated downward in recent years by both Argentina and Brazil.

In mid-June, YPFB accepted a request by Brazil’s state-controlled Petrobras to lower its minimum imports of Bolivian gas to just 10mn m³/d. “In light of the extraordinary situation we face, we approved the force majeure requested by Petrobras because of Covid-19,” YPFB said in a note.

The original long-term contract called for Petrobras to import a minimum of 24mn m³/d and a maximum of 30mn m³/d, with the minimum cut to 14mn m³/d as recently as March. The contract was to expire in 2019 but has been extended because over its 20-year term, Petrobras has often taken less than it has contracted.

Argentina’s state-run Enarsa successfully renegotiated its long-term gas contract with Bolivia in February 2019, with deliveries slashed to 11mn m³/d in the summer months of October through April and 16-18mn m³/d during the colder months, when consumption surges for heating purposes. Contracted volumes were supposed to average 20mn m³/d through 2026.

Brazil’s imports of Bolivian gas are likely to continue to decline substantially more than Argentina’s in a relatively low-price post-Covid world, given the relatively high cost of developing Vaca Muerta shale compared with its own off-shore sub-salt resource.

On that note, Petrobras is maintaining its 2020 target of 2.7mn barrels of oil equivalent (boe)/d for domestic oil and gas output, despite Covid-associated lockdowns hammering global oil and gas consumption and prices. The company produced 2.76mn boe/d in the second quarter, a decline of 3.5% compared with the first quarter but up 8% year-on-year. Domestic production overall for the first six months of the year averaged 2.81mn boe/d, an increase of almost 12% compared to the same period in 2019.

In contrast, the Argentine government is attempting to revive activity in Vaca Muerta after a total collapse earlier this year. The number of fracking stages in the region was zero in April, compared with 430 in March. The number of active oil and gas rigs in Argentina as a whole has declined from around 60 in the first half of 2019 – before the country’s latest debt crisis and Covid – to no operating rigs now. According to Argentina’s energy secretariat, domestic gas production declined by 10% year-on-year to 126mn m³/d in June.

It was reported in mid-August that Argentina is to launch yet another price support programme for gas in the near future, with guaranteed prices for producers of around $3.40/mn Btu for the next four years.

Alternate markets

With gas exports to Argentina and especially Brazil in decline, the Bolivian government had been negotiating to export gas by pipeline to Paraguay and via LNG liquefaction plants on the coasts of Argentina and Peru for overseas markets.

In November 2018, Bolivia’s minister for hydrocarbons Luis Alberto Sanchez and Paraguay’s minister for public works Arnoldo Wiens signed a memorandum of understanding on building a gas pipeline between the neighbouring land-locked countries. “Talks are very advanced and we have spoken with the outgoing and incoming presidents about the project,” said Morales at the time. The two governments agreed to a final design study in June 2019, but the project has since stalled with the political situation in La Paz.

The same can be said for potential LNG export facilities in Argentina and Peru, with both showing progress until the ouster and self-imposed exile of Morales last November.

At a news conference in Buenos Aires in April 2019, Morales and his Argentine counterpart, Mauricio Macri, announced plans to widen energy integration between their two countries, including construction of liquefaction terminals on Argentina’s coast to export Bolivia’s gas. These projects would benefit from existing pipelines, as Argentina’s need for Bolivian gas continues to decline, and joint financing by Argentina’s state-controlled YPF SA and YPFB.

In January 2019, the energy ministers of Bolivia and Peru met to discuss construction of a gas pipeline and a liquefaction plant to export LNG to Asia, with detailed engineering of the gas pipeline already underway. “We’re interested in investing in Peru’s Ilo port,” Sanchez said after his meeting with counterpart Francisco Ismodes.

In 2018, Morales and the president of Peru Martin Vizcarra met three times to discuss bilateral relations, including Bolivia's use of the Ilo port in southern Peru and building a liquefaction plant there to export its gas. There were grounds for optimism: in 1992, Peru granted Bolivia a 99-year lease over a 17.5-km stretch of coastline near Ilo for industrial and port development. In June 2015, Morales and the then president of Peru Ollanta Humala first agreed to study the Ilo gas pipeline and LNG project during a summit in Lima.

To conclude, a potential lack of markets, made worse by present political turmoil, pose serious impediments to Bolivia’s efforts to attract investment and exploration activity by international oil companies.