BP’s statistical review: normal service will be resumed shortly [Gas in Transition]

Although there had been economic weakening around the globe and trade tensions that more than hinted at a recession late in 2019, this was nothing compared with what was to follow. But despite the slowdown of activity – across industry, transport and refining – the 6.2% drop in the year’s carbon emissions from energy use was unexpectedly trivial. The same volume was seen as recently as 2011.

As well as the 9% drop in oil demand and a 4.2% drop in coal demand, renewables at 11.3% saw their biggest ever share of the power mix. But those changes have not been permanent: the International Energy Agency (IEA) estimated late last year that emissions were on track for a full recovery this year.

At a webinar devoted to BP’s 2020 Statistical Review of World Energy, organised by the Columbia Center on Global Energy Policy July 12, the IEA’s Laura Cozzi estimated that only a quarter of the CO2 emissions lost were permanent or “structural”; the remainder were “cyclical” and bouncing back. And a geopolitics analyst and academic Meghan O’Sullivan said the reduction represented a “paltry” return given the huge cost.

The drop in carbon emissions, and the economic loss sustained worldwide expressed in the vague terms of gross domestic product, equate to a carbon price of $1,400/metric ton. And according to BP’s chief economist Spencer Dale, such a drop – albeit at a much lower price in a planned reduction – is needed every year for the next 30 years to reach an 85% reduction by 2050.

BP envisages $100/mt by 2030 and like many peers – and indeed the attendees of the G20 summit in Venice – the company is fighting for a carbon border adjustment price to ensure a level playing field. In a communique after the summit, the finance ministers agreed on the need for a wide set of tools to cut emissions, phase out hydrocarbon subsidies and create a more sustainable economy, including “if appropriate the use of carbon pricing mechanisms and incentives while providing targeted support for the poorest and the most vulnerable.”

But emissions will probably continue to grow for years, rather than shrink as needed to meet the remaining carbon budget. The world’s population is growing and becoming a little wealthier, and several billions are still without secure electricity supplies. The amount of coal, gas and oil needed to ensure heat and light for all will also have to be affordable in a just world while decarbonising adds costs – and particularly heavily in the early years before pay-back.

The goals of the Paris Agreement cannot become reality unless there is a mechanism whereby the richer countries take on the task of supporting poorer countries. But as Dale points out, the ‘nationally determined contributions (NDCs)’ that governments have pledged following Paris are precisely that: national. And many developing countries are putting economic growth ahead of climate change measures.

Even the NDCs promised add up to only 70% of the world’s total – assuming they are fully implemented. This assumption itself is far from straightforward and likely to entail new laws in many countries. The UK for example has no legal means yet of forcing homes to convert from gas, despite the plans to decarbonise heating. Nor is there provision for the localised kind of energy markets that will be needed for the different parts of the country to choose the most appropriate form of net zero carbon emissions. Even installing smart meters in every household by 2020 failed to overcome customer inertia.

Stranded assets

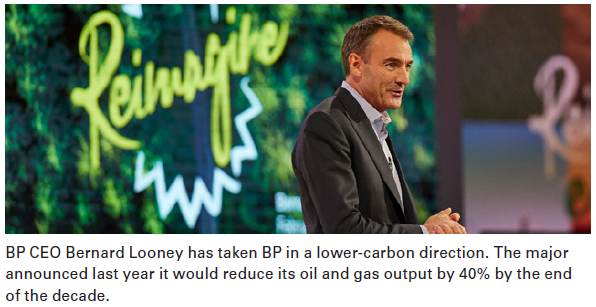

Stranded assets is just one of the problems facing the upstream oil and gas sector: how to avoid being left holding the most expensive oil and gas when the remaining carbon budget runs out. A lot will be left unproduced. BP has gone further than its European competitors along the decarbonisation path, planning to end the decade with 40% less production than at the moment. In keeping with that thinking, last year it dropped a standard industry metric – proved reserves replacement – from its targets.

And as the European Commission unveiled its Fit for 50 strategy July 14, BP CEO Bernard Looney posted his support for it on social media, saying he expected “those policies to stimulate low-carbon consumer demand and create big business opportunities for companies like ours.” Disposals of its upstream assets will free up cash for BP’s investments – although the new owners might not operate the fields with the same approach as BP did under Looney.

As the company steps back progressively from oil and gas, it will shift its weight instead towards electric vehicles or renewable energy projects, where its trading expertise will help bridge the gap in revenues from conventional energy. It does not plan to be a pure-play renewable energy company but it will integrate the different parts of it and optimise them through trading, while developing the value chains necessary for blue and green hydrogen, carbon capture and storage and ammonia.

BP has made much of its Q1 trading success in the US, where Texas froze in the winter. But trading itself not immune to setbacks either. Anglo-Dutch Shell, whose trading team has in the past compensated for poor commodity prices, warned of a poor performance when it announces its next quarterly result, despite strong prices for oil and natural gas. “Trading and optimisation results are expected to be significantly below average and similar to the first quarter 2021,” it said July 7.

In attitude if not in reality, BP stands in contrast with TotalEnergies. The French company, as it rebranded itself in late May, made no bones about the need for oil and gas to subsidise the “utility” – single digit – rates of return that are achievable from its development of renewable energy projects. These appear to owe at least as much to financing muscle as to any proprietary technology, but even here there are risks as competition for this kind of assets goes up.

Upstream however TotalEnergies has made some of the biggest and cost-competitive gas finds in recent years and it will make the most of those. Italian energy company Eni has also made much of its upstream prowess, with large finds in both oil and gas.

Cognitive block

The UK government's high level climate action champion Nigel Topping told a BP-hosted event July that companies with a long history as an oil and gas producer suffered from a cognitive block that prevent them from viewing the world of energy as a neutral outsider.

Suggesting that BP was in denial about the rate of change, he quoted a slide in Dale's opening remarks, showing the historical growth in wind energy 2014-2020 and its actual growth over that same period as forecast at the outset by BP. There was a widening gap as lower costs have led to more rapid deployment of wind. He interpreted that to mean that BP was continuing to invest money in outdated technology on the basis of wrong forecasts. Dale said that this showed that learning was happening faster as more wind farms were built.

Topping said other forecasts would show similar discrepancies as costs fall elsewhere too. The industry will gain knowledge, he said: "Industrial change always happens." This was already the case with batteries, he said: "BP consistently gets it wrong."

On the same grounds he challenged BP's senior vice president for strategy and sustainability, Giulia Chierchia. She had said that in the future, green and blue hydrogen would probably share the market equally, based on likely supplies of renewable electricity available for electrolysis. Topping said that falling costs would tip the scales in favour of green hydrogen even though at the moment there is a lot of research suggesting it is a multiple of the cost of blue.

Chierchia however said that she came from outside the industry and so could not be accused of repeating past mistakes. She was formerly a partner at McKinsey.

Removing the pollution

Speaking for the investment community, BlackRock's Paul Bodnar said that removing pollution from the investment cycle was a very long-term business. This is despite the massive increase – about 11 times as much money is now invested in ESG-branded as was the case five years ago.

Asset life and contractual arrangements mean emissions can extend far into the future. He gave the example of coal-fired power generation, where he estimated that about three quarters of the installed capacity would not be cost-competitive with renewable energy by 2025 but over 90% of coal is shielded from competition by government policies and long-term contracts. What is needed to reduce emissions is not building wind farms, but increasing the rate at which dirty assets are turned off, he said.

Shipping and steel mills were also in that group of long-lived but relatively dirty assets. In that context, Bodnar said, it was not surprising that when the pandemic-induced freeze began to thaw, emissions should rebound – even if some people did decide to work from home more often or to take fewer flights.

The year in figures

- Gas prices declined to multi-year lows: US Henry Hub averaged $1.99/mn Btu in 2020 – the lowest since 1995, while Asian LNG prices (Japan Korea Marker) registered their lowest level on record ($4.39/mn Btu).

- Gas demand fell by 81bn m³ or 2.3%. Nevertheless, the share of gas in primary energy continued to rise, reaching a record high of 24.7%. Declines were led by Russia (-33bn m³) and the US (-17bn m³), with China (22bn m³) and Iran (10bn m³) contributing the largest increases.

- Inter-regional gas trade fell by 5.3%, completely accounted for by a 54bn m³ (10.9%) drop in pipeline trade.

- LNG supply grew by 4bn m³ or 0.6%, compared with the 10-year average rate of 6.8%/yr. US LNG supply expanded by 14bn m³ (29%), partly offset by declines in most other regions, notably Europe and Africa.

- China and Malaysia used 0.5 EJ and 0.2 EJ more coal respectively but global coal production was down 8.3 EJ (5.2%).

- Renewable energy (excluding hydro) rose by 9.7%, lower than the 10-year average (13.4%/yr) but the increase (2.9 EJ, of which wind was 1.5 EJ) was similar to increases seen in 2017, 2018 and 2019.

- China was the largest individual contributor to renewables growth (1.0 EJ), followed by the US (0.4 EJ). Europe, as a region, contributed 0.7 EJ.

- Electricity generation fell by 0.9% – more than the decline in 2009 (-0.5%), the only other year since BP’s records begin in 1985 when electricity demand fell.

- The share of renewables in power generation increased from 10.3% to 11.7%, while coal’s share fell 1.3 percentage points to 35.1% – a new low in BP’s data series.

- The oil price (Dated Brent) averaged $41.84/b in 2020 – the lowest since 2004 – while demand fell by a record 9.1mn b/d, or 9.3% – its lowest level since 2011. China was virtually the only country where demand rose (220,000 b/d).

- Global oil production shrank by 6.6mn b/d, with OPEC accounting for two-thirds of the decline. Libya (-920,000 b/d) and Saudi Arabia (-790,000 b/d) saw the largest OPEC declines, while Russia (-1.0mn b/d) and the US (-600,000 b/d) led non-OPEC reductions.

- Refinery use fell by a record 8.0 percentage points to 74.1%, the lowest level since 1985.