Canada’s COP26 admonitions not welcomed by oil and gas sector [Gas in Transition]

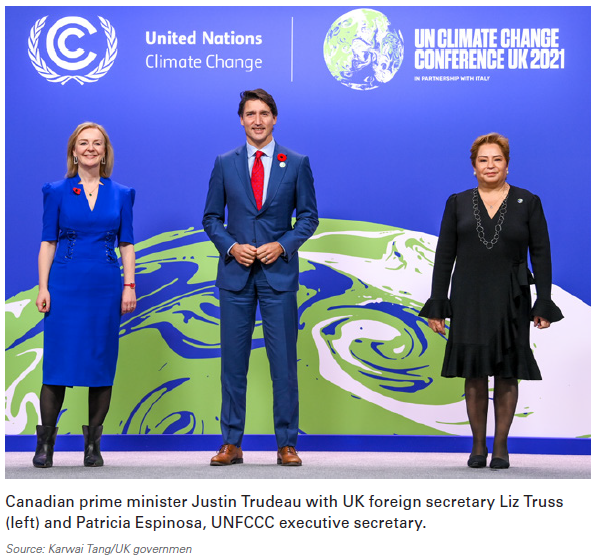

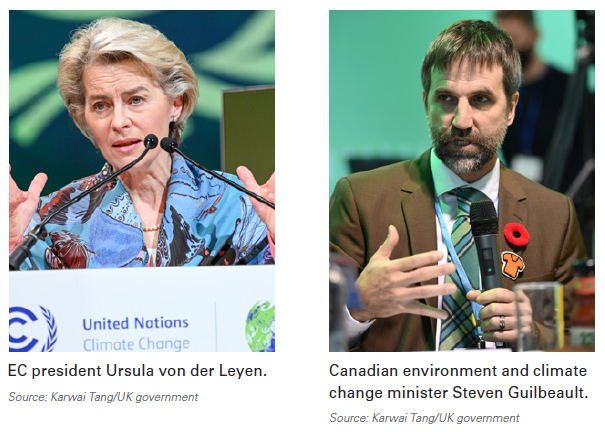

Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau trekked to COP26 in Glasgow with ministers from his newly-shuffled cabinet in tow, including natural resources minister Jonathan Wilkinson, who moved over from environment and climate change, and former Greenpeace activist Steven Guilbeault, whose appointment to the environment file raised eyebrows throughout the western Canadian oil and gas sector.

Once in Scotland, Trudeau wasted little time pressing his claim as a world leader on the global climate stage, announcing his government would impose a hard cap on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from the oil and gas sector. He initially made the promise while campaigning in September for a federal election that returned his minority government.

“We’ll cap oil and gas sector emissions today and ensure they decrease tomorrow at a pace and scale needed to reach net-zero by 2050,” Trudeau said November 1 in his opening two-minute speech to COP26 delegates. “That's no small task for a major oil and gas producing country. It's a big step that’s absolutely necessary.”

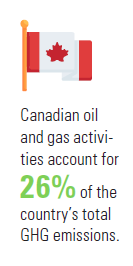

In 2019, Canada’s oil and gas sector – largely based in Alberta and other western provinces – accounted for about 191mn mt of GHG emissions, 26% of the country’s total. The transport sector accounted for about 186mn mt, but no hard cap – aside from a steadily-rising carbon tax that will hit C$170/mt by 2030 – has yet been imposed on that sector, or on any other sector of the Canadian economy.

Oil and gas leaders were quick to condemn the cap as reckless and imposed without any consultation with the provinces – which constitutionally control the production of natural resources – or with the industry itself.

“The commitments at COP26 were made without consultation, approval, a plan, or a penalty mechanism for non-compliance,” industry veteran David Yager tells NGW. “It would appear that climate virtue-signalling on the global stage in Glasgow was more important than any understanding or communication of how the new programme will work or be implemented.”

Brad Hayes, CEO at consulting firm Petrel Robertson, also saw little of substance in any of Trudeau’s comments in Glasgow.

“Canada tried to take ‘leadership’ positions by out-promising others, particularly oil-producing economies, in terms of their emissions reductions aspirations,” he told NGW. “I saw little to back these other than a promise to clamp down on oil and gas production.”

After making the announcement in Scotland, Trudeau directed Wilkinson and Guilbeault to work with the federal Net-Zero Advisory Body, a group of Canadian business leaders charged with detailing Canada’s road to net-zero by 2050, on how to actually impose the cap.

Reckless

Grant Fagerheim, CEO of Calgary-based Whitecap Resources, in an interview with the CBC, warned of the dangers of such a “reckless” move when the government has no idea how it is to achieve the target.

“Setting out virtue-signaling commitments with no real firm targets is dangerous, and it’s reckless because at the end of the day, this is about the things that we can't live without – food, heat, clothing and transportation.”

But Wilkinson, speaking with reporters in a virtual media availability on November 5, noted that several Canadian producers have committed to net-zero by 2050. A hard cap, he said, will actually help them meet those targets.

“What we’re saying to them is, okay, let’s partner and put a framework around that and let’s work together on how that’s going to be done,” he said.

Beyond imposing caps on his own country’s producers, Trudeau urged other COP26 delegates to pursue a global tax on carbon. Right now, he said, only about 20% of global emissions are covered by some form of a tax on carbon, whether it’s a direct tax on emissions or a cap-and-trade system for sharing emission credits.

Beyond imposing caps on his own country’s producers, Trudeau urged other COP26 delegates to pursue a global tax on carbon. Right now, he said, only about 20% of global emissions are covered by some form of a tax on carbon, whether it’s a direct tax on emissions or a cap-and-trade system for sharing emission credits.

“We should be ambitious and say as of right here today that we want to triple that to 60% of global emissions should be covered by a price on pollution in 2030,” he said during a panel discussion on the sidelines of the COP26 summit.

The panel included European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen, who praised Canada’s leadership on the carbon tax file and supported his call for some kind of global carbon-pricing system.

“It's been proven – it helped us decouple growth from greenhouse gas emissions,” she said. “So you can prosper while cutting emissions.”

No interest in Article 6

The EU has operated an emissions trading scheme since 2005 that caps emissions on certain industries and allows others to sell emissions reduction credits to others.

But a global carbon price would necessarily require finalisation of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement to pave the way for a system of internationally transferred mitigation outcomes (ITMOs).

The final communique from COP26 said the so-called Paris Rulebook, setting out guidelines for how commitments under the Paris Agreement would be delivered, had been agreed by delegates after six years of negotiations.

“This will allow for the full delivery of the landmark accord, after agreement on a transparency process which will hold countries to account as they deliver on their targets,” the communique said. “This includes Article 6, which establishes a robust framework for countries to exchange carbon credits through the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.”

But few details surrounding Article 6 were released by summit officials and Canada, at least, seems lukewarm to the idea of a global emissions credit trading system, Guilbeault told reporters in a virtual media availability on November 9, before the Article 6 details were finalised.

“Canada hasn't made use of the provision under Article 6 for international emissions trading,” he said. “I’m not saying that we will never do it, it’s not currently in either of our plans, the climate plan or the enhanced climate plan.”

Still, he said Article 6 is important to other countries, and its rules should be robust.

“Whatever is agreed upon should make sure that the atmosphere is seeing a difference, and that we’re not double counting, that we’re not artificially reintroducing into the atmosphere emissions that wouldn’t be allowed to be there in the first place,” he said. “So we feel we don’t have a strong opinion about the mechanism itself, but we feel it needs to be robust and transparent and accountable.”

“Whatever is agreed upon should make sure that the atmosphere is seeing a difference, and that we’re not double counting, that we’re not artificially reintroducing into the atmosphere emissions that wouldn’t be allowed to be there in the first place,” he said. “So we feel we don’t have a strong opinion about the mechanism itself, but we feel it needs to be robust and transparent and accountable.”

Canada also took a leading role, alongside Germany, in holding the feet of the developed world to the fire around its Paris pledge to help fund less-developed economies in meeting their own transition objectives.

In the early days of the Glasgow summit, Wilkinson and Jochen Flasbarth, Germany’s state secretary at the Ministry for Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety, talked up their joint Canada-Germany Climate Finance Delivery Plan, which had been released prior to COP26.

The plan provides clarity on when and how developed countries will meet the $100bn annual climate finance goal through to 2025 agreed at Paris in 2015 – a pledge which has yet to be fulfilled.

“It is critically important for developing countries to be able to trust that the developed world will make good on its promises, starting with the $100bn climate finance goal,” Wilkinson said. “Canada doubled its climate finance commitment (to C$5.3bn over the next five years) earlier this year and I hope that we can instil confidence and trust that developed countries will deliver on their promises to the developing world and that Canada will continue to be a constructive player to this end internationally.”

And, as announced prior to COP26, it has signed on to the Global Methane Pledge, a joint EU-US initiative to reduce global methane emissions by at least 30% from 2020 levels by 2030 that now has been adopted by more than 100 countries. Canada’s own target, supported by producers, is to reduce methane emissions from oil and gas activities by 75% by 2030.