Catching up with the EU [NGW Magazine]

BP’s incoming CEO Bernard Looney wants to reposition the company in response to the changing climate. He is therefore considering a new strategy that may require a major shake-up of the corporate structure and the way in which it does business.

The overhaul is likely to include extending emissions targets to its products -- such as jetfuel – once they have been used by customers, which are known as Scope 3 emissions (see separate feature on the IEA report).

He also told the Financial Times in January that he wants to inject ‘realism’– a rare commodity – into the debate as there is still robust demand for hydrocarbons.

This realism will be welcome, if it can indeed be injected. All the international oil and gas companies (IOCs) are under heavy pressure from activists and shareholders – now often the same people -- to do more to limit global warming, but the world still needs hydrocarbons.

Even the International Energy Agency (IEA) has joined in with its latest report, and this is a body normally keen to see plenty of upstream investment so that oil flows and prices are stable (see separate feature).

Eliminating greenhouse gas emissions takes a lot of thought: the IOCs have to balance it with sustaining their traditional business that funds that work – and also generates the high revenues that keep their shareholders, such as pension funds, satisfied. That means they have to keep investing upstream.

But no matter what they do, it is not going to be enough to satisfy Greenpeace and those like it, who appear to be caught up in a galloping inflation of anti-consumerist rhetoric. Commenting on Looney’s plans, Greenpeace said: “The role of oil companies is to stop being oil companies – to stop wasting money drilling for unburnable new reserves.”

The polarisation of the climate change debate is further demonstrated by the situation that the Norwegian oil company Lundin Petroleum is finding itself in. The discoverer of the giant Johan Sverdrup oil-field, it has just pledged to become carbon neutral by 2030 – by reducing emissions from operations, improving energy efficiency and developing carbon capture mechanisms. It is even replacing ‘Petroleum’ with ‘Energy’ in its name.

Rather than welcoming the explicit change of direction, Greenpeace swiftly accused the energy company of hypocrisy, adding that the “only real answer” to the climate emergency is to quickly phase-out all extraction and burning of fossil fuels. Lundin simply has to pivot or die” – uncompromising and extreme, but also unhelpful and impractical.

As the IEA has made it abundantly clear in its report, the demand for oil and gas will continue well into the future, including in Europe. Annual depletion of reserves means that more resources need development to meet this demand affordably.

Oil and gas companies must regain trust

Energy companies have been slow to accept the realities and risks of climate change, being tied to oil, gas and in some cases coal as sources of supply. They have also been reluctant to shift capital expenditure into low-carbon activity, although some have introduced incentives for their divisional teams to come up with energy- or emission- saving ideas for their department.

But as energy researcher Nick Butler says, “the generalisation of specific mistakes into condemnation of the whole sector is… both unfair and dangerous. Unfair, because most energy companies work to high standards of behaviour, pay their taxes and provide essential services to consumers. Dangerous, because the policy debate needs the expertise of those who will be expected to keep providing the energy the world needs.”

These are strong reasons to keep oil and gas companies as active participants in the public policy debate in Europe and the preparation of the Green Deal. They have more to offer from within than from without, given their technological reach and inhouse knowledge. And as Butler says: “That is the only way the corporates can regain trust and the only way we will reach viable, practical solutions to the challenge of climate change.”

The message is not getting through

At a lively discussion at the European Gas Conference (EGC2020) in Vienna on January 27 on natural gas and the European Green Deal, it became apparent that the message from the oil and gas industry, if there is one, is not getting through to the policy-makers.

The European Green Deal has the potential to become a framework to guide energy in Europe to a net-zero carbon future over the next 30 years or so. But without direct participation by the energy industry, it is in danger of being unbalanced.

So far, the agenda on climate change seems to be dictated by activist non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and what European politicians and members of parliament (MEPs) consider to be the wishes of their electorates. In addition, the renewables industry is managing successfully to present gas as no more than a short-term successor to coal on the way to a zero or negative carbon future.

Methane emissions across the value chain are a big part of the problem that gas faces. The industry has no convincing measured and certified data on methane emissions, or emissions associated with LNG, to present. It needs an agreement on how to measure data and an agreed methodology on how to certify it.

There has also been a lot of talk from the industry about plans to invest in carbon capture and storage as a key solution, but that needs policy support, it says, or a very much higher carbon price to provide the incentive to invest. But waiting until that price is reached is not a narrative that suits the European Commission (EC) and general, 2050-targeted, statements are not enough either.

Meanwhile the EC’s own efforts to increase the carbon price have been delayed for as long as possible by coal-dependent member states.

The view from Brussels

The deputy director of the EC’s energy directorate Klaus-Dieter Borchardt put the organisation’s view clearly at EGC2020. Previously, EU energy policies were market-driven. This is no longer the case, he said: they will now have to meet climate objectives.

He said that the Green Deal is not just about energy. It is also about industry, society, technology and competition. For example, gas will still be needed in industry as feedstock and in petrochemicals. But all policies must work towards the over-riding objective of net-zero emissions by 2050.

And in that context he returned to a persistent problem the EC has with gas: long-term contracts have a lock-in effect that eventually will jeopardize the 2050 targets. The EC has been opposed to these for a long time, but on anti-trust rather than green grounds.

The Green Deal also means affordability: failing to deliver that fundamental requirement may provoke more unrest such as the gilets jaunes movement in France.

In addition, getting other countries to go along, particularly with the proposed Carbon Border Tax, might not work. The US has already reacted negatively to this idea.

To cite an interview with researcher Andrei Belyi (NGW Vol 5 #1), if the EU really did take the climate action seriously, it should assist switching from coal to gas across the world, beyond Europe, rather than heaping another economic burden on its own voters, which is implicit in the Green Deal.

Belyi sees a risk that heavy industry will be offshored, and then subject at the EU border to a ‘protectionist’ carbon tax.

New gas in old pipes

Given that the long-run objective is net-zero emissions by 2050, there will have to be some migration towards green gases, depending on how much progress is made on other carbon extraction technology such as woodland and biomass.

Borchardt said: “We all need to work together to find solutions for methane leakage. We need better methodologies for measuring, reporting and certifying methane emissions transparently.” Without a solution it will make the role of natural gas in energy transition difficult.

In the longer-term natural gas will be substituted by clean gases. It will then constitute a second pillar to electrification. But a regulatory framework will also be needed to facilitate this process, he said.

The global dimension

Although the EC takes the view that global energy outlooks are not relevant to its plans, they are nevertheless relevant to the oil and gas industry and the rest of the world. In energy terms, what happens in the EU is only a small part of the story.

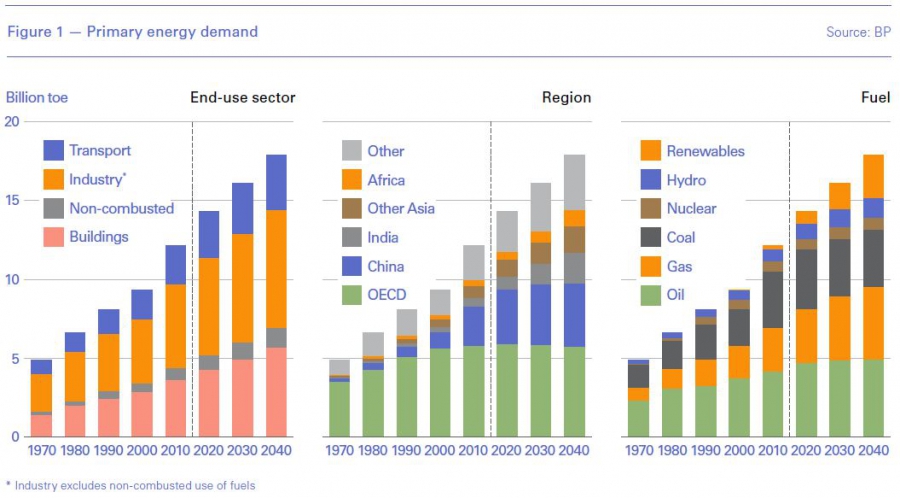

As the BP Energy Outlook 2019 shows (Figure 1), while OECD primary energy demand – which includes Europe -- remains flat post-2020, China, India and the rest of Asia carry on using more until 2040. As a result the energy narrative in these countries will diverge ever more widely from Europe’s.

In addition, in global terms, the bulk of the industry is controlled by the state-owned exporting companies holding over 60% of proven reserves. The international energy majors account for only a very small proportion of global supplies of oil and gas.

Rising populations demanding higher standards of living mean that all energy sources are needed: fossil fuel, low-carbon energy and renewables.

Europe’s energy transition then depends on events elsewhere in the world, rather than a driver. Some countries are even actively resisting efforts to move to lower carbon economies. For them, the short-term, pressing issues such as wider electrification, reducing air pollution and raising people out of fuel poverty are urgent and weigh more heavily with voters than what may happen in the longer term.

What needs to be done

The oil and gas industry has a serious role to play and in the process help set a realistic agenda for achieving Europe’s target of net-zero emissions by 2050. Such an approach may attract interest within the European Parliament, where there are MEPs concerned about Europe going it alone, about increasing climate targets and about the proposed approach to gas.

In the discussion with Jonathan Stern of the Oxford Institute of Energy Studies, Borchardt said that “many believe in the future of gas in Europe.” But he also said that many activist NGOs and MEPs, who believe they won the battle with coal, are now attacking natural gas, portraying it as the ‘new coal’.

The oil and gas industry must address this. So too must the EU member states – mostly in eastern Europe -- that depend on gas, particularly if they phase out coal.

Both the industry and member states must demand a change of direction so that natural gas is accepted as part of the efforts to address climate change. There is a need for a narrative on the future role of gas in Europe – if the industry believes there is one – how it plans to deal with emissions – especially methane – and how it fits within Europe’s climate change targets. This could form the basis of constant dialogue with the EC, from within.

But those in the oil and gas industry who appear to favour the idea of ‘wait and see’ on what comes out of EC’s decarbonisation strategy, which it plans to finalise by 2021, are leaving it too late.

The industry must take the lead and prepare well-supported strategic papers that the EC can understand, so that it can make a difference in the forthcoming regulatory process. This is the way it can contribute to the development of viable, practical, solutions to the challenge of climate change.