China sees pause in LNG growth [Gas in Transition]

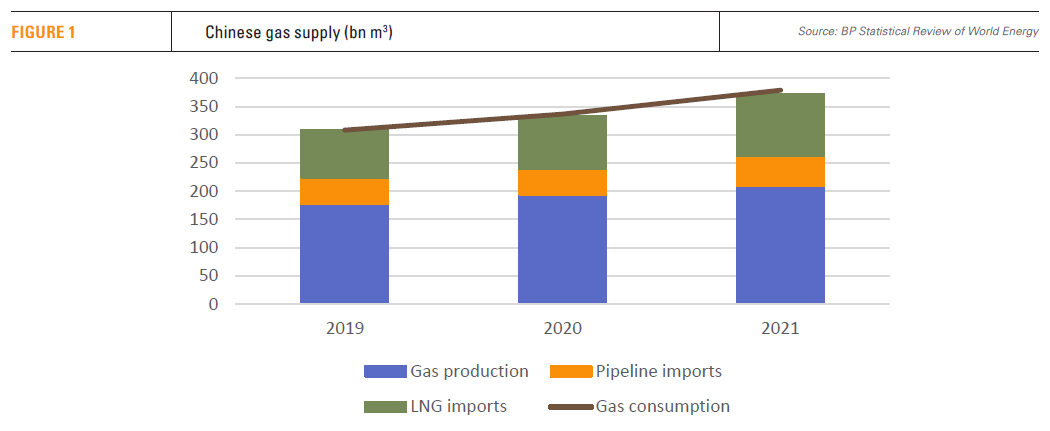

China became the world’s largest LNG importer in 2021, with deliveries of 109.5bn m3 (78.93mn mt) easily overtaking the 101.7bn m3 received by Japan, according to the BP Statistical Review of World Energy, 2022. Chinese LNG imports increased by about 15.5bn m3 or 16.8% year on year, with purchases made on a spot basis accounting for about a third of the total.

With almost 150bn m3/yr of LNG import capacity available at the end of 2021, and more under construction, it was generally expected that LNG imports both could and would grow substantially in 2022. But, in the first half of the year, the reverse happened.

Between January and May, China’s LNG imports fell by 19.6% year on year to 26.49mn mt, according to data from the General Administration of Customs. The declines in April and May were particularly brutal, with imports down 34.5% and 28.1% on the year at 4.35mn mt and 4.93mn mt, respectively.

While most commentators anticipate that LNG imports will recover in the second half of the year, few expect the recovery to reverse the decline experienced in the first half. For instance, in early June, consultants Wood Mackenzie projected that Chinese LNG imports in 2022 as a whole would “decrease by an unprecedented extent to 70mn mt.”

Gas supply and demand trends

There are various reasons for what, if it unfolds, will be only the second annual decline in Chinese LNG imports, following the 1% fall recorded in 2015. The unprecedentedly high price of the fuel is clearly a major factor, but on the demand side, limited growth is also moderating China’s appetite for LNG.

Gas demand had been expected to grow significantly in 2022, albeit at a lower rate than in 2021, when it increased by 12.8% to 378.7bn m3, according to BP data. State oil company Sinopec’s Economics and Development Research Institute, for instance, projected at the start of the year that demand would grow by about 7% to 395bn m3. Sinopec’s assessment of 2021 gas demand was 370bn m3, somewhat lower than BP’s estimate.

A 7% increase in gas demand now seems highly optimistic and the fall in LNG imports will be largely offset by increases in both piped imports and domestic production.

From January to May, Chinese pipeline imports increased by 11.3% to 18.42mn mt (see figures 1&2). The rise reflects the ramping up of gas supplied under long-term contracts held with Russia’s Power of Siberia pipeline and with Turkmenistan and other Central Asian producers.

Meanwhile, domestic gas production increased by 5.8% year on year to 92.4 bn m3 (67mn mt) in the same period, according to data from China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). Already the subject of renewed government emphasis on grounds of security of supply, indigenous gas production has been given further impetus by the sharp rise in internationally-traded gas prices.

The return of King Coal

The extent to which domestic gas production can be increased will be strictly limited by technical and geological factors in the near to medium term, but the same is not true of China’s highly flexible coal production. Concerns over security of supply and rising international energy prices have led the government to push domestic coal output and, in the process, go slow on environmentally-inspired measures to reduce coal production and consumption.

The consequences of government support for domestic coal combined with its price competitiveness are apparent from production data published by the NBS. Chinese coal output from January to May increased by 10.4% year on year to 1.81bn mt, with use of the fuel growing across the economy. In particular, coal use accounted for a majority of the 3.2 trillion kWh of electricity generated in China during the first five months of 2022 (see figures 3&4).

The impact of increased coal use – alongside high hydropower output – on gas demand for power generation was compounded by relatively warm winter weather in 2021/22. This reduced gas demand for power generation and especially for heating.

Economy stalls

However, the overriding cause of the squeeze on Chinese gas and energy use in general – and on LNG as one of the most expensive energy sources in particular – has been the problems convulsing the Chinese economy since late 2021.

China started to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic earlier than most countries. GDP grew by 8.1% in 2021, compared with only 2.2% in 2020, helping to drive the 12.8% increase in gas demand, 16.8% increase in LNG imports, and the surge in international energy prices.

However, the fragility of the global economy, as a result of the pandemic, remained a problem for China’s manufacturing and export sectors, especially as energy prices began rising. This was exacerbated from early 2022 by the country’s adoption of the Zero-COVID policy, entailing stringent lockdowns and mass testing. This resulted in widespread disruption of economic activity and a shattering of already shaky consumer sentiment.

On top of this came Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. While the war has had little direct impact on China’s economy to date, and created some opportunities in terms of access to resources, it has exacerbated existing uncertainties in the global and domestic economy.

The impact of these factors on the Chinese economy has been savage. The official target for GDP growth in 2022 remains unchanged from the 5.5% set at the start of the year. But this now appears unattainable. Retail demand – one of the largest components of GDP – fell by 1.5% year on year between January and May. Over the same period, real estate investment fell 4%, while industrial production grew by only 3.3% (see figure 5).

Much of the carnage occurred in April and May, after GDP grew by 4.8% in the first quarter. Retail sales slumped by 11.1% year on year in April, while industrial production was down 2.9%. In May, steel production fell 2.3%, cement production slumped 17% and electricity output dropped 3.3% year on year.

As the extent of the problems became apparent, analysts cut their forecasts for Chinese GDP growth. In June, the World Bank revised downward its forecast of 5.1% to 4.3%. Some of the revisions made by commercial banks are lower still, with JP Morgan projecting 3.7%, Nomura 3.3% and UBS 3% for the year.

Which of these forecasts proves most accurate will depend on how Beijing’s COVID-19 policies evolve, how domestic economic activity recovers, and what changes occur in the global economy. Domestic activity is expected to respond positively to the economic stimulus package announced by Beijing at the end of May. But the future path of COVID-19 and the measures taken to combat it remain profoundly uncertain.

Meanwhile, the outlook for the global economy looks far from promising. In June, the World Bank downgraded its forecast for world GDP growth in 2022 from 4.1% to 2.9%, followed by growth of only 3% in both 2023 and 2024.

Within that forecast, the World Bank projects that Chinese GDP will grow by 5.2% in 2023 and 5.1% in 2024, low rates of expansion for the Chinese economy. Nonetheless, this may prove overly cautious -- the 8.1% jump in Chinese GDP in 2021, from what amounts to a standing start, is a reminder that the Chinese economy can confound the gloomiest of expectations.

Future demand

The extent and timing of economic recovery will inevitably have a profound impact on China’s demand for gas, and thus LNG. Domestic output and piped imports may be preferred, but in the near to medium term supplies of both will be relatively inelastic.

The Power of Siberia pipeline will reach its full capacity of 38bn m3/yr by 2025, and it is unclear when the next large-scale tranche of Russian pipeline supplies will come on line. As for domestic gas, the government’s latest five-year plan, restated in March 2022, sees only modest growth in production to 230bn m3/yr in 2025.

China’s renewed love affair with coal also needs to be assessed cautiously.

China’s renewed love affair with coal also needs to be assessed cautiously.

It seems highly likely that coal will retain some of the markets it had been expected to lose to gas as a result of coal-to-gas switching programmes. But, in some regions and sectors, especially the heating market, these programmes are still likely to be implemented because of local and environmental pressures to reduce the problems associated with coal use.

In all, this suggests that as the economy recovers, even at a relatively modest rate, more gas and LNG will be needed. As a result, China’s position as the largest LNG importer is likely to be restored in the near future.

Nonetheless, there are likely to be marked differences in the Chinese LNG business going forward. In particular, the shift from spot to long-term contracts that saw over 30bn m3/yr of long-term agreements signed in 2021 is continuing to gain pace, with deals for new US and Qatari LNG among those under negotiation. Spot trade is likely to suffer, reviving only when new LNG supply projects come on line and prices fall.