Chokepoint threats to LNG trade are rising [Gas in Transition]

Transit risk for the LNG industry has increased, owing to a lack of water in the Panama Canal and the threat of wider conflict in the Middle East. The latter could potentially impact LNG flows through the Strait of Hormuz and Gulf of Oman, the world’s busiest oil and LNG waterway, with devastating consequences for LNG supply, global energy security and greenhouse gas emissions.

While issues with the Panama Canal are immediate, Middle East tensions are barely less so, centred around the potential broadening of the fierce conflict between Israel and Hamas in the Gaza Strip.

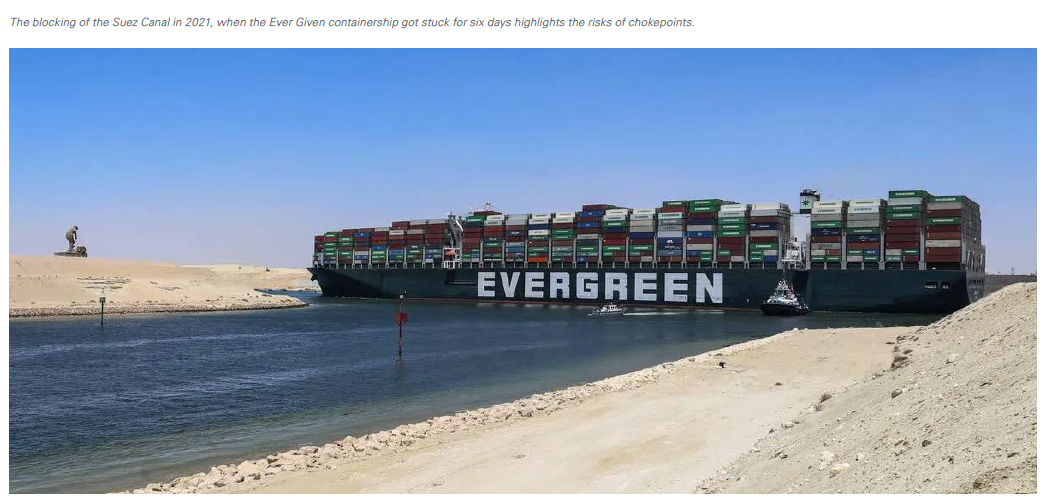

Pressure on one chokepoint inevitably puts pressure on others. Other key waterways are the Suez Canal and the Strait of Malacca. In 2021, the accidental wedging of the Ever Given container ship for one week across the Suez Canal provided a sharp reminder of the importance of the canal to global trade in general and LNG shipping in particular. About 7% of global LNG exports pass through the Suez Canal each year.

Complete closure of a critical waterway has obvious supply-side implications, but waterway congestion also impacts the LNG Carrier (LNGCs) market because the increased time LNGCs spend on the water reduces the supply of available vessels, driving up costs and delaying deliveries. This occurs both as a result of ships waiting to make transits and by decisions to avoid the blockage and take longer routes to the desired destination. Either way LNGCs stay longer on the water for each voyage.

Moreover, as global LNG trade expands, particularly in the context of the failure of energy relationships based on pipeline trade, the importance of key waterways increases.

Concern over existing chokepoints will also drive forward the growing use of Arctic maritime routes, which are becoming more accessible, owing to reduced ice cover in the Arctic Ocean. The overall trends are concerning: more traffic and more weather risk, as a result of climate change, are likely to result in more operational accidents, even if political disruptions are discounted.

Panama Canal struggles to stay afloat

Ships traversing the Panel Canal from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean save about 8,000 nautical miles (14,800 km), while those moving between the US east and west coasts save 3,500.

The most important source of water for the Panama canal is the Chagres River, which at the time of the canal’s construction was dammed to create Gatun Lake. The canal works by elevating ships 26 metres through a series of locks to the lake. If travelling southbound, i.e. entering the Canal from the Atlantic side, ships then sail across Gatun Lake to the Culebra Cut, which is a 7-km long twisting channel. Ships descend via the Pedro Miguel Locks (9 metres) then through a 2-km channel to the Miraflores Locks, which brings them back to sea level. They then sail into the Pacific Ocean via a final 11.3-km channel.

The most important source of water for the Panama canal is the Chagres River, which at the time of the canal’s construction was dammed to create Gatun Lake. The canal works by elevating ships 26 metres through a series of locks to the lake. If travelling southbound, i.e. entering the Canal from the Atlantic side, ships then sail across Gatun Lake to the Culebra Cut, which is a 7-km long twisting channel. Ships descend via the Pedro Miguel Locks (9 metres) then through a 2-km channel to the Miraflores Locks, which brings them back to sea level. They then sail into the Pacific Ocean via a final 11.3-km channel.

The capacity of the Canal was expanded in 2016 with the addition of a third set of locks, which were designed to reduce water consumption and accommodate larger ships. This occurred the same year that production started up from the US’s first modern liquefaction plant Sabine Pass, located on the US Gulf Coast, allowing US LNG quicker access to Asian LNG markets.

The third set of locks raise ships from and to sea level directly from the Gatun Lake, without using an intermediary channel.

Each ship that passes releases an average of 52mn gallons of water into the sea using the old locks and about 22mn gallons using the new locks, which makes sufficient rainfall to supply Gatun Lake essential to the Canal’s smooth operation. An average of about 14,000 transits takes place each year. Each transit takes about 10 hours, with about 38 vessels using the Canal each day.

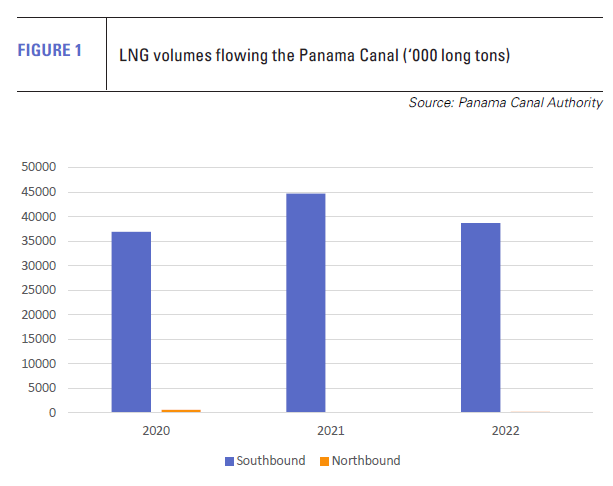

In 2022, 38.7mn tons of LNG transited the canal from the Atlantic to the Pacific (see figure 1). The Panama Canal is a crucial waterway for US LNG plants on the Gulf Coast, which is where the majority of current and under construction US LNG capacity is sited.

At the end of October, the Panama Canal Authority (ACP) said that the month of October had been the driest on record, attributing the lack of rain to the El Niño phenomenon. Rainfall in October was 41% lower than usual, reducing water levels in Gatun Lake. The outlook is that Panama will end the rainy season, which runs until the end of the year, with minimal reservoir levels. Around 50% of the country’s population also depend on Gatun Lake for water.

As a result, APC has been forced to reduce the number of reservation slots for November to 25, in December to 22, in January to 20 and, in February, to just 18. The average number of days non-booked ships are standing in line had risen to five-six days by mid-November. Draught restrictions also mean that the largest ships have to carry less cargo to avoid the risk of running aground.

APC is now looking for additional sources of water for Gatun Lake, such as a dam on the Indio River from where water could be transferred 8 km by pipeline. Another option is to extract water from the Bayano Lake. Construction of a new reservoir is estimated to take between five to six years, as it would also need to be filled -- the speed of which would depend on the amount of rainfall -- assuming legislative restrictions and potential political opposition can be overcome.

While the current lack of rainfall is being attributed to El Niño, reduced rainfall as a result of climate change is also a major concern.

Limited traffic through the Canal would make even larger the freight advantage new LNG plants sited on the Canadian and Mexican west coasts will enjoy, as well as helping to redirect more Middle East LNG into Asia as US cargoes compete for market share in Europe.

Strait of Hormuz and the Suez Canal

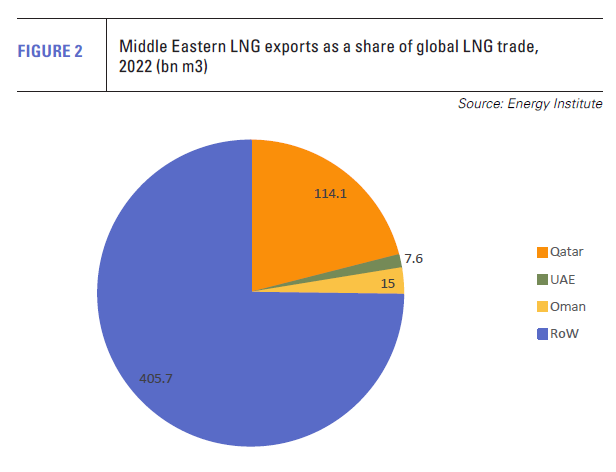

The Strait of Hormuz is the most transited waterway in the world for LNG traffic, owing to Qatari LNG exports, although it also handles LNG flows in and out of the UAE and to Kuwait, a growing market for the liquified fuel. The expansion of Qatar’s LNG production capacity from around 77mn t/yr at present to 110mn t/yr and then 126mn t/yr over the course of this decade will make the Strait of Hormuz even more critical to the global flow of LNG (see figure 2).

The Gibraltar Strait is the second most transited waterway, followed by the Malacca Strait and then the Suez Canal, Bab el-Mandeb route. Closure of the Panama Canal would result in much greater traffic via the Strait of Gibraltar, Suez Canal and then Malacca Strait to reach Asia, and to only a slight increase in trade around South America crossing the Magallanes Strait, according to models assessing the impact of such an event.

This would increase the importance of the already important Suez Canal, which has seen record transits and revenues in recent years. A new record for daily transits of 107 was achieved in March. In 2020, a total of 686 laden and unladen LNGCs passed through the canal. The laden vessels account for about 7% of global LNG trade. Key users are Qatar bringing LNG into Europe and Russian LNG producers from February to May when the Arctic Northern Sea Route is closed by heavy ice.

Dredging and development works, which have added a new channel in the Canal’s southern section, have increased capacity substantially since the Ever Given accident.

As the Suez Canal is at sea level it does not suffer the same climate change risks related to rainfall as the Panama Canal.

The effects of even a temporary closure of the Suez Canal have already been demonstrated, but at least alternative maritime routes exist. Not so with the Strait of Hormuz, which is at risk of closure as a result of wider conflict in the Middle East, stemming from the current war between Israel and Hamas in the Gaza Strip.

There are many possible scenarios in which conflict could escalate. Israel’s invasion of Gaza could prompt one or more of its enemies to attack on a different front, for example the Iran-backed Lebanese Hezbollah, eventually drawing Iran more directly into military confrontation with Israel. The US has already bombed Iran-backed militias in Syria in response to attacks from Iranian-backed militias on US forces.

There are many possible scenarios in which conflict could escalate. Israel’s invasion of Gaza could prompt one or more of its enemies to attack on a different front, for example the Iran-backed Lebanese Hezbollah, eventually drawing Iran more directly into military confrontation with Israel. The US has already bombed Iran-backed militias in Syria in response to attacks from Iranian-backed militias on US forces.

In the context of wider conflict, Iran could attempt to close the Strait of Hormuz, an action which it has often threatened. If effective, this would have a devastating impact on the LNG market and the world economy because of the huge volumes of oil – around 20% of global production -- which pass through the waterway on a daily basis.

The general consensus is that a closure of the Strait remains a remote possibility because of the economic importance that oil and LNG flows have for many of the major states in the region, including Iran. But just because an event is unlikely doesn’t mean it cannot happen. Moreover, the mutual economic benefits of Russia-Europe gas flows did not prevent war in Ukraine.

As around 25% of the world’s LNG exports flow through the Strait of Hormuz and Gulf of Oman, such a closure would be catastrophic, given the lack of alternative routes. This would be particularly so in the context of heightened European demand for the fuel, owing to the war in Ukraine, and in the context of climate change. Such a serious blow to global LNG supply would almost certainly drive Asian coal consumption higher, if not in other countries around the world.