Congolese LNG plans move forward [Gas in Transition]

Congo-Brazzaville looks set to be one of the next countries to join the list of Africa’s LNG producers. Italy’s desire for new sources of gas has prompted Eni to speed up and expand its LNG plans in the Central African country, as well as in other African markets, to replace and displace Russian gas imports.

The presence of Italian Foreign Affairs Minister, Luigi di Maio, at the signing of a preliminary agreement in Brazzaville this year suggests that all output from the new project will be shipped to Italy as the European scramble for African gas intensifies.

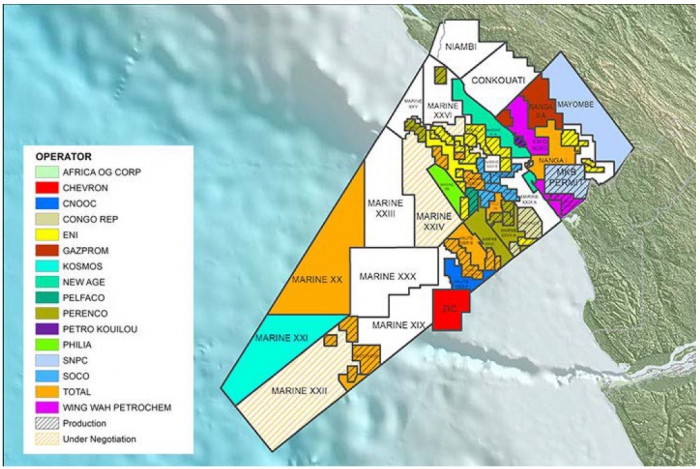

At the end of April, Eni and the government of Congo-Brazzaville signed a letter of intent “to increase gas production and export...primarily through the development of an LNG project” using gas from its Marine XII block. Eni has not specified that it will be a floating LNG (FLNG) project, but given the anticipated size and timescale this seems to be the only option.

Under the terms of the agreement, Eni plans to produce 3mn tons of LNG a year starting in 2023, an ambitious, but not unachievable timetable. While it has proven difficult to monetise smaller, stranded gas reserves in the Gulf of Guinea, the completion of the Golar LNG project in 2018 off Cameroon, which actually has smaller and more scattered gas reserves than Congo-Brazzaville, has shown other governments in the region what is possible.

Prior preparation

Eni signed a memorandum of understanding with the government over developing gas reserves last year, but the published statement focused on domestic gas supply and biofuels production rather than LNG. However, it seems that LNG production was also planned, as Eni secured a change in the tax terms of its production sharing agreement (PSA) on the Marine XII concession to include LNG development.

In addition, this February, just before the war in Ukraine broke out, the company signed a heads of agreement (HoA) with US firm New Fortress Energy (NFE) for an LNG facility in Congo-Brazzaville, which envisages a 1.4mn ton/yr LNG project fed by associated gas from offshore fields on Marine XII.

It was intended that the project would use NFE’s Fast LNG system, which combines modular, midsize liquefaction technology with jack-up rigs or other vessels. NFE says that Fast LNG, which it hopes to deploy in several different locations around the world in the near future, can be developed more quickly and at a lower cost than existing FLNG vessels.

Eni has not disclosed whether its new agreement with Brazzaville would incorporate the same technology on a larger scale to achieve the new planned production capacity. However, sources in Africa suggest that the higher 3mn ton/yr volume could be developed in two phases, so two NFE FLNG vessels is a possibility.

Gas will be provided by both associated and non-associated fields on Marine XII, including the Nené Marine and Litchendjili Marine oil and gas fields, which are located in shallow water just 17km offshore. Eni has also pointed out that the LNG project will help it end all gas flaring on the block.

A Jersey-based company called New Age (African Global Energy), originally proposed developing an FLNG project on Marine XII when it held a 25% stake in the block, with first production targeted for 2021. However, the company sold its share to Lukoil for $800mn in September 2019. Eni holds a controlling 65% stake, with the remaining 10% owned by state-owned Société Nationale des Pétroles du Congo.

Lukoil is not formally sanctioned by the EU, US or UK, but its founder Vagit Alekperov is. Alekperov earlier this year resigned from his positions within the company.

Congo-B operations

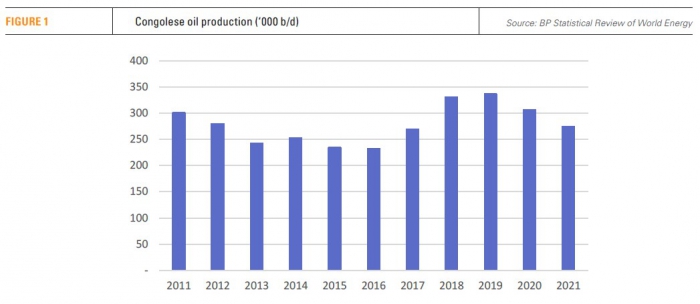

Eni produced 25mn barrels of oil equivalent of gas in Congo-Brazzaville last year, plus 16mn barrels of oil. It is the operator of ten producing blocks in the country and holds non-operated equity in two more, all under PSAs. Congolese oil production fluctuates, but generally stands at around 300,000 b/d, making it one of the most important producers in Sub-Saharan Africa, with crude accounting for more than 90% of the country’s export revenue.

Little effort has been put into developing the country’s gas potential or establishing the size of known reserves. Estimates of the country’s gas reserves differ, but are generally put at about 10 trillion ft3 (283bn m3), with annual production of just 49bn ft3 (1.4bn m3), all of which is consumed by the domestic power sector.

Roman strategy

At present, only Nigeria, Angola, Equatorial Guinea and Cameroon export LNG from Sub-Saharan Africa, although new capacity is under development in Senegal and Mauritania and the Eni-operated Coral Sul floating LNG project in Mozambique is due to ship its first cargo in October. Further down the line, more substantial capacity is likely to be developed onshore in Mozambique and Tanzania.

Attention on more marginal potential sources of production, such as Congo-Brazzaville, has increased. European governments have been keen to secure new sources of gas supply since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent imposition of European sanctions. Most recently, on 27 July, Russia’s state-owned gas company Gazprom cut flows through the Nord Stream 1 pipeline to Germany to less than a fifth of the normal capacity, apparently in an effort to stop European companies and governments from building up gas reserves ahead of the winter.

The Italian government has announced that it wants to become completely independent of Russian gas imports by the second half of 2023. In June, then Italian prime minister Mario Draghi announced that the proportion of Italian gas imports sourced from Russia had fallen from an average of 40% in 2021 to 25% in June. Rome is racing to secure alternative sources of energy, including offshore wind, but, as in Germany and other European countries, fast tracking FLNG projects is central to its short-term plans. Eni’s planned Congolese project fits neatly into this strategy.

It was reported in April that the Italian government had signed a deal to import 1.0-1.5bn m3 of gas a year from Angola, presumably from the existing Angola LNG plant in Soyo, following hot on the heels of deals to import Algerian and Egyptian LNG. Angola LNG has struggled to secure sufficient gas supply but, at the end of July, Eni took the final investment decision (FID) on what will be Angola’s first non-associated gas project, developing the Quiluma and Maboqueiro fields, to supply Angola LNG.

It was reported in April that the Italian government had signed a deal to import 1.0-1.5bn m3 of gas a year from Angola, presumably from the existing Angola LNG plant in Soyo, following hot on the heels of deals to import Algerian and Egyptian LNG. Angola LNG has struggled to secure sufficient gas supply but, at the end of July, Eni took the final investment decision (FID) on what will be Angola’s first non-associated gas project, developing the Quiluma and Maboqueiro fields, to supply Angola LNG.

It has also been reported that Eni is in talks with the government of Mozambique. The development of that country’s two big onshore LNG projects has been held up by the Islamist insurgency in the area. Reflecting the insecurities of onshore development, Eni appears to have opted for an additional offshore solution. Eni’s CEO Guidi Brusco has confirmed that the company is considering a second FLNG vessel, which he said could come onstream in just four years.

Project responsibilities for the existing Coral Sul FLNG project are split, with Eni taking charge of offshore operations in Area 4 and project partner ExxonMobil in charge of onshore Area 4 assets. An FID on a second FLNG facility would need to be cleared with ExxonMobil and the other Coral-Sul shareholders, China's CNPC and Mozambican state-owned Empresa Nacional de Hidrocaronetos.

Domestic politics

Eni has operated in Congo-Brazzaville since 1968 and all its current commercial gas production in the country, including on the Litchendjili Marine field, is supplied to the 484 MW Centrale Électrique du Congo (CEC) power plant, which accounts for 70% of Congolese power generation.

The Italian company holds a 20% stake in the plant, while the Italian firm’s relationship with the government has also been strengthened by its investment in extending the power grid in the country’s commercial capital Pointe-Noire and building a transmission line between Pointe-Noire and the capital Brazzaville.

It is this relationship that has enabled the company to move quickly on developing a larger than planned LNG project. As part of the new letter of intent, Eni has agreed to boost gas supplies within the country, assist in the development of renewable energy for power generation and biofuels projects.

President Denis Sassou Nguesso has ruled the country since 1979 apart from a break between 1992 and 1997. Elections are generally considered unfair, with opposition political leaders subject to long prison terms. Labour relations in the country have been difficult. Most recently, oil industry workers went on hunger strike in late June and early July as part of their campaign for wages to be increased by the rate of inflation.

As a result of the autocratic system, foreign investors keen to invest in Congo-Brazzaville rely on building relationships with Sassou Nguesso and his family. There seems little chance of him losing an election or being overthrown, but he is now 78 years old and it is difficult to predict what might happen after his death.

Contracts signed between foreign companies and other African autocrats have been cancelled or rewritten once they leave power. French and US investigations are underway into corruption allegations against relatives of the president, but seem reluctant to target the president himself. Sassou-Nguesso has steadily moved closer to Beijing in the face of western opposition to his autocratic rule. For the moment, however, the desire for early LNG production appears to have overcome any concerns about a potentially unstable investment environment.