Country Focus: Colombia: A Small and Uncertain Market for LNG [LNG Condensed]

This suggests LNG could start to play a larger role in the country’s baseload energy provision, taking advantage of cheap US shale, the growing number of US LNG plants based along the US southern coast and the relatively short haul across the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea to Colombia.

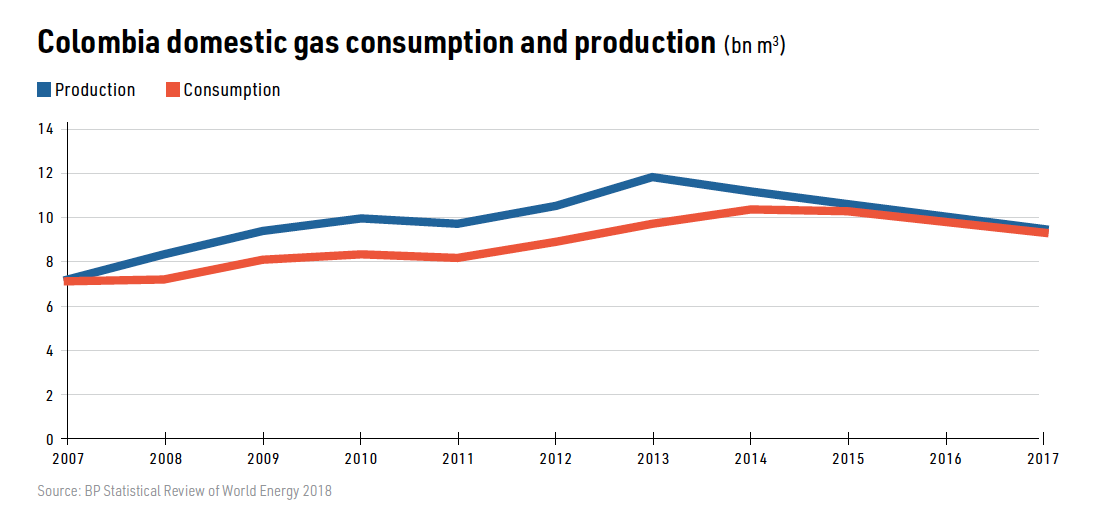

However, LNG demand in the country faces some potentially lethal challenges. Colombia does not lack gas so much as gas production. Either off- shore gas development or shale gas could switch the country’s gas balance from growing deficit to surplus over the next decade. A resumption of gas imports from Venezuela is another medium-term possibility.

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

In addition, Colombia has only just started to scratch the surface when it comes to renewable energy. The country still has significant unexploited hydro potential, and its first renewables tenders have confirmed the low prices seen in other Latin American auctions in recent years for wind and solar. Renewable energy targets have already been adopted by energy planners, but the experience of other Latin American countries suggests ambitions could soon grow. With more renewables in the mix, gas burn may prove low, providing little impetus to LNG demand growth.

BACK-UP ROLE

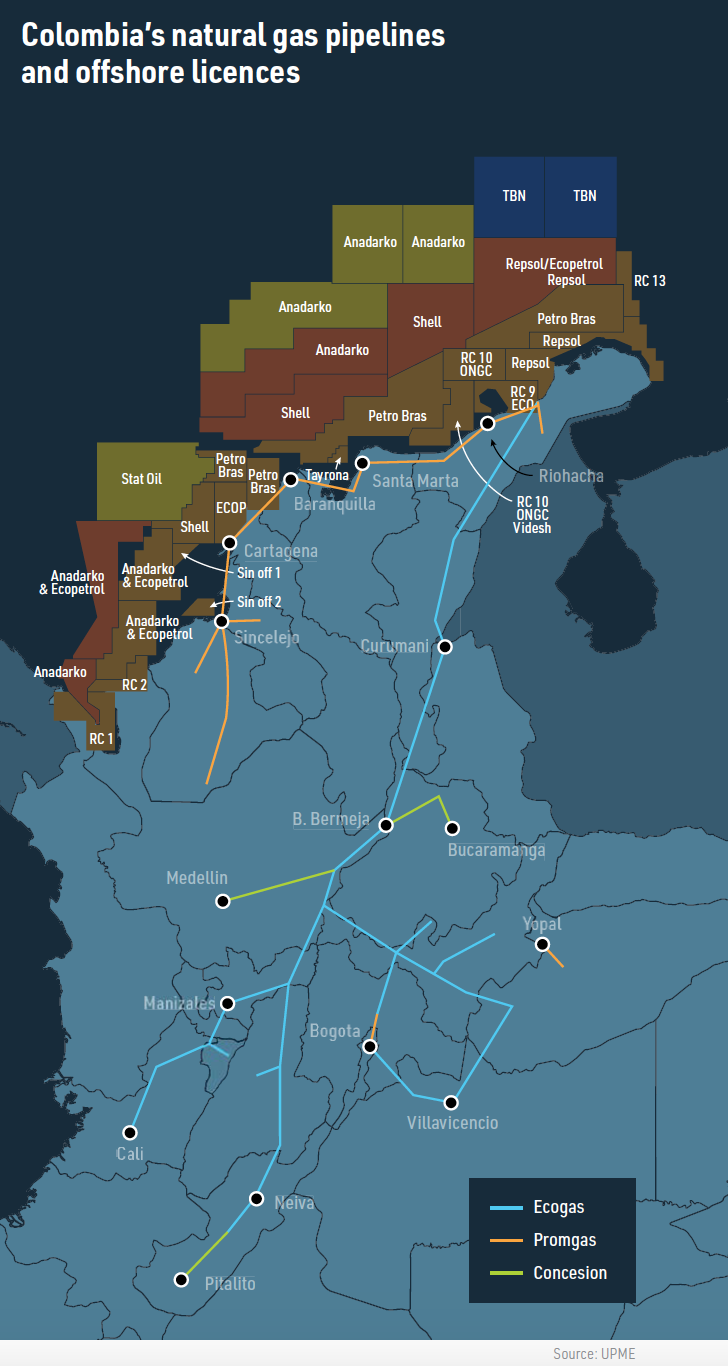

Colombia’s LNG imports amounted to a meagre 0.25mn mt/yr in 2018, accord- ing to GIIGNL, the International Group of LNG Importers. The cargoes were bought on a spot basis from the US and Trinidad & Tobago, arriving at Colombia’s first and so far only LNG terminal at Cartagena de Indias. The terminal has 3mn mt/yr capacity, a 750-metre pier and a 10-kilometre pipeline connecting it to the national gas transportation system.

The terminal, a floating storage and regasification unit (FSRU), is owned 51% by Colombia’s Promigas and 49% by Baru LNG. It is operated by Sociedad Portuaria El Cayao (SPEC) and used primarily to supply gas to power plants to meet fluctuations and shortfalls from the country’s hydro plants.

However, given falling domestic gas production, the country is already considering a second terminal, this time on its Pacific coast at Buenaventura. Rather than act as a strategic reserve to support low hydro generation, this would meet residential and industrial demand, including for power generation. A tender for the terminal and associated pipeline, estimated to cost $650mn, is expected this year, but there is consider- able uncertainty over who will take the gas. The project is unlikely to proceed until firm offtake agreements have been reached.

Nonetheless, the idea of a third terminal has also been floated. Ricardo Ramirez, head of the government’s UPME energy planning unit, said last year that a third terminal could become necessary towards the end of the next decade. That view appears to see LNG’s role expanding well beyond its current one as a flexible back-up to hydro.

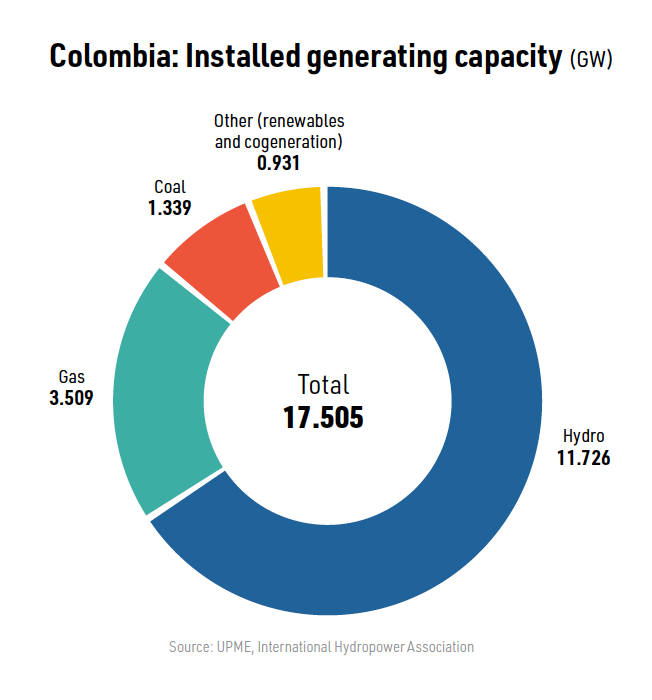

Colombia currently has just over 17 GW of installed generating capacity, of which 11.7 GW is hydro. The country has 3.5 GW of gas-fired plant, 1.2 GW of coal-fired plant, with the remainder made up of renewable energy sources and cogeneration. The government’s energy planning unit, UPME, forecasts that by 2028, installed capacity will reach 24.2 GW, including 2.8 GW of wind, 1.2 GW of solar and 3.5 GW from other sources including hydro, gas and coal.

HYDRO VULNERABILITIES

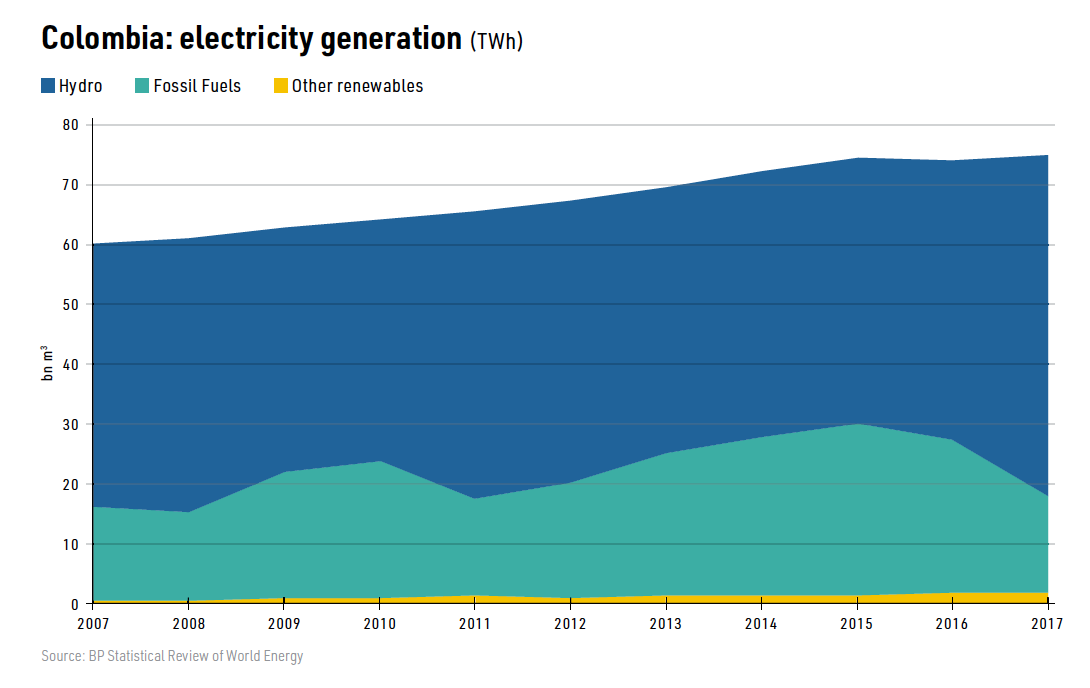

Interest in gas for power generation has been stimulated by the country’s dependence on hydropower, which makes up more than two- thirds of installed capacity and provides the majority of generated power. Hydropower, often seen as steady and reliable, can see generation vary significantly from year to year, depending on the level of rainfall and ice melt, both factors which have become more unpredictable with climate change.

In addition, the el Nino weather phenomenon, driven by sea surface warming in the central-east equatorial Pacific, can lead to huge variations in hydro performance. Between 2013-2016, Colombia experienced drought conditions, reducing hydro generation below normal levels. But then, in 2017, a huge increase in rainfall, and the addition of 100 MW of new capacity, saw hydro generation jump to 57.3 TWh from 46.8 TWh the year before. The impact on fossil fuel generation was large: it fell from 26 TWh in 2016 to just 16.2 TWh in 2017.

Problems with hydro generation’s variations have been exacerbated by major construction problems with the $4bn, 2.4 GW Hidroituango hydro plant, which could potentially meet 16% of the country’s electricity demand. Last year, land- slides blocked tunnels rerouting the river around the under-construction dam, causing it to fill, flooding the engine room and sparking a desperate race to raise the project’s embankment levels. Mass evacuations downriver were necessary.

Problems are ongoing. Local reports in February said two floodgates had been closed, causing the Cauca river to recede, causing significant environmental damage. The experience overall has damaged both faith in the country’s ability to deliver large hydro projects and popular support for them.

DOMESTIC GAS SUPPLY

Colombia also has its own gas. It produced 10.1bn m3 in 2017, but is struggling to maintain output volumes. 2017 production was down 6.5% from 2016 and down further from a peak of 13.2bn m3 in 2014. The government has forecast a gas supply deficit within five years.

Having formerly exported gas to Venezuela, Colombia’s growing needs prompted the construction of a pipeline to import gas from its neighbour, but the imports were sporadic and then suspended altogether as Venezuela descend- ed into its current political and economic crisis. Longer-term though, the potential to resume these imports exists.

Other potential sources of gas lie within Colombia’s own boundaries. The US Energy Information Administration has estimated Colombia’s technically recoverable shale reserves at 55 trillion ft3 (1.6 trillion m3).

In addition, oil majors have taken an interest in the country’s deepwater offshore potential, following a major discovery in 2017 by state oil company Ecopetrol and US company Anadarko. The Gorgon-1 discovery suggested gas intervals of 80-110 metres and was close to earlier finds, Kronos-1 and Purple Angel-1, suggesting a viable development cluster.

Following changes to contractual terms, sector momentum appears to be gathering. In April, Ecopetrol and ExxonMobil signed contracts with Spain’s Repsol for further offshore exploration and production. In March, Shell signed for two blocks and then brought partner Noble in to operate them with a 40% interest. Brazil’s Petrobras has also had exploration success offshore Colombia.

Naki Mendoza, director of the energy pro- gram at the Americas Society/Council of the Americas, has pointed out that this presents a major policy decision for the government. The development costs of offshore gas are high and the gas would have to travel long distances to the country’s main demand centres. LNG might prove a cheaper option.

However, as the gas market in Colombia is small, it would only take one or two major developments to change the gas balance, while domestically-produced gas would bring wider economic benefits than imported LNG in terms of invested capital and government revenues. Under president Ivan Duque, who was elected last year, domestic gas supply development appears to be the chosen path.

RENEWABLES

A second threat to potential LNG demand comes from renewable energy sources. Colombia has been slow to adopt renewables, but equally seen the huge drop in prices achieved via auctions by countries like Mexico, Chile, Brazil and Argentina.

Its first tender, held earlier this year, did not go quite according to plan. No contracts were awarded, despite the participation of 27 local and international companies bidding 1.5 GW of projects for 500 MW of capacity auctioned. The small number of potential winners fell foul of anti-trust laws. According to local reports, mines and energy minister Maria Fernanda Suarez said that some of the bids were so low that they matched current generation prices.

However, the results of the country’s reliability charge auction in March did see success for renewables. 1.39 GW of renewables capacity was awarded, mostly wind, but with 238 MW of solar. These projects are expected to start generating from 2022. The tenders demonstrated plenty of pent-up demand by companies for project development and their willingness to offer competitive prices.

Hydro too will have an impact, assuming Hidroituango eventually comes into operation. In addition, there were 125, mainly small, hydro projects in 2017 at pre-feasibility stage, which could add about 5.6 GW of power, according to UPME.

LNG OUTLOOK

The prospects for a second LNG terminal in Colombia should benefit from its proposed south- ern, Pacific Coast location, more than a 1,000 km from the northern Atlantic Coast offshore discoveries – further taking the existing pipeline system into account.

In addition, an FSRU could be put in place relatively quickly, ahead of both the expected emergence of a gas supply deficit within five years and, most likely, substantial offshore gas production. But longer term, a role in baseload energy provision for LNG looks likely to be limited by domestic and regional gas supplies and the growth of renewable energy sources.

This article and more in LNG Condensed Volume 1, Issue 4 - April 2019 - Sign Up Free below and never miss an issue:

_f300x384_1558007325.jpg) In this Issue:

In this Issue:

> Sanctions loom over Russian LNG

> Editorial: Off Message in Shanghai

> Feature: Natural gas and the hydrogen economy

> Feature: South Korean LNG set for growth

> Country focus: Colombia: an uncertain market for LNG

> Project spotlight: Delfin LNG: an innovative approach to FLNG and more!

Sign up now to receive LNG Condensed monthly FREE (after filling out the form you will be redirected to LNG Condensed's archive where you can find every issue already published available for download):