Country focus: Philippines [Gas in Transition]

The Philippines is set to join the ranks of LNG importers this year, underlining the growing importance of southeast Asia to the global LNG market.

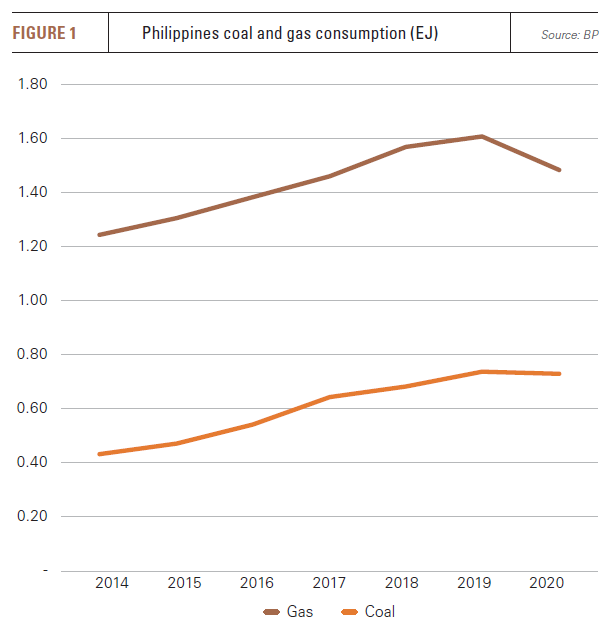

The introduction of LNG to the country’s energy system should help stem coal use in power generation, which has been on the rise since the late 1990s, and address the looming exhaustion of the country’s only major domestic gas field, Malampaya (see figure 1).

According to a report prepared by USAID, energy consumption increased by 85% in the Philippines between 2006 and 2019, significantly higher than the regional average of 55%.

Coal market uncertainties

High LNG prices in 2021 raised concerns that developing countries would turn away from the fuel. However, southeast Asia’s backstop, coal, is proving just as problematic in the short term, even before its emissions-heavy generation profile and the decline in interest from international financiers is taken into account.

Indonesia, one of the world’s largest coal exporters, instituted an export ban on January 1, owing to a lack of coal for its domestic power sector, leading to howls of protest from southeast and east Asian countries dependent on the fuel. Moreover, coal prices rose sharply in 2021 and an unofficial ban by China on Australian coal exports threw the usual supply chains into chaos as China sought alternative supplies.

The Indonesian coal export ban has hit the Philippines particularly hard, as power demand ramps back up to pre-pandemic levels. In 2020, the Philippines imported 43.5mn metric tons of coal, 70% of which came from Indonesia, with additional supplies sourced from Australia and Vietnam.

Domestic gas

In addition, gas output from the country’s largest gas field, Malampaya, in northwest Palawan, is in terminal decline. The field has been the mainstay of the country’s gas sector since it began production in 2001.

Gas production is used almost entirely for domestic power generation. New exploration, despite some offshore prospects, has been bedevilled by unattractive investment terms and tax disputes. There was only one active rig in the Philippines onshore and none offshore in December, according to Baker Hughes data.

Malampaya’s gas supply contract for the 1.2-GW Ilijan power plant expires in July and for other plants under Service Contract 38, the expiry occurs in 2024. Some field production could last until 2027-2029, but supplied volumes are increasingly erratic and unpredictable.

Output, which has supplied up to 40% of the gas for Luzon’s 3.5-GW of gas plant, suffered restrictions in March through June last year and again in September. The lack of gas has forced some gas-fired power plants to shift to liquid fuels at substantial additional cost.

LNG to the rescue

The introduction of LNG should provide the Philippines with better gas supply security as it grapples with an uncertain coal market and expands its renewable energy capacities.

There are two LNG import facilities under construction. First Gen Corporation will install a floating storage and regasification unit (FSRU) to supply LNG to its First Gen Clean Energy Complex near Batangas City, which powers the Luzon grid.

In April last year, First Gen announced a five-year time charter for the BW Paris, a 162,400-m3 FSRU owned by BW Gas Ltd. The unit has baseload capacity of just over 5bn m3/year and can deliver gas at a peak rate of 21.2mn m3/d. Taking base and peak operations into account, the FSRU has a capacity of 5.26mn mt/yr. It can also load LNG onto smaller vessels and trucks to allow wider distribution. The FSRU is expected to start operating in the third quarter of this year. The cost of the LNG facility is estimated at about $260mn.

First Gen operates four gas-fired plants in the Philippines all serving the Luzon grid, Santa Rita (1 GW), San Lorenzo (500 MW) and San Gabriel (420 MW), which are CCGTs and provide baseload power, as well as the 97-MW Avion open-cycle gas peaking plant. Output from Santa Rita and San Lorenzo is sold to the Manila Electric Co., Meralco, under 25-year agreements. San Gabriel has a six-year contract with Meralco which runs until 2024.

The second project is a $304mn, 3mn mt/yr FSRU also to be located in Batangas City, which will supply the Ilijan power plant. An additional 850 MW of capacity is expected to come into operation later this year at Ilijan, which is operated by SMC Global Power Holdings, the power generation arm of San Miguel Corp. The power plant currently supplies about 10% of the power needed on the Luzon grid.

The FSRU will have 137,000 m3 of storage and truck loading facilities. Singapore’s Atlantic Gulf & Pacific (AG&P) initiated the project and was granted a notice to proceed by the Philippines Department of Energy in February 2021. However, the project application has been passed to Philippines-based Linseed Field Power Corp., with AG&P becoming the project contractor, operating in partnership with Japan’s Osaka Gas. The facility is expected to be complete by the end of the second quarter.

Additional contracts were awarded last year to marine engineering company Acteon and to CB&I, a subsidiary of US engineering company McDermott.

In addition to the Ilijan expansion, other companies are looking to LNG-to-power supply chains to meet the country’s growing electricity demand. Philippine renewable energy and power distribution company AboitizPower has announced interest in the construction of a 1-GW gas-fired power plant to provide baseload power to the Luzon grid and, according to company statements, is looking at more than one potential location for new gas power projects.

In September, Japan’s JERA, a joint venture between Tokyo Electric Power and Chubu Electric Power, agreed to purchase 27% of the outstanding shares in Aboitiz Power Corp. for $1.58bn. The two companies signed a memorandum of understanding to collaborate on fuel sourcing and management of the LNG needed for potential LNG-to-power projects. Aboitiz is targeting 9.2 GW of power generation by 2030 split equally between thermal and renewable energy.

LNG and renewables

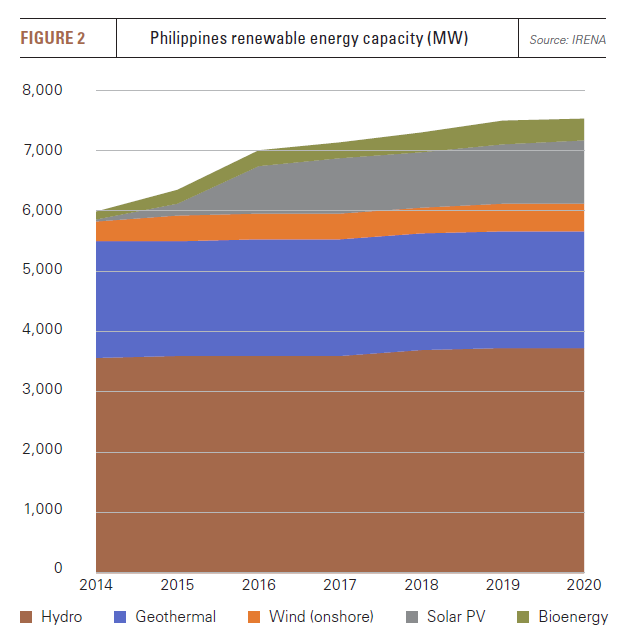

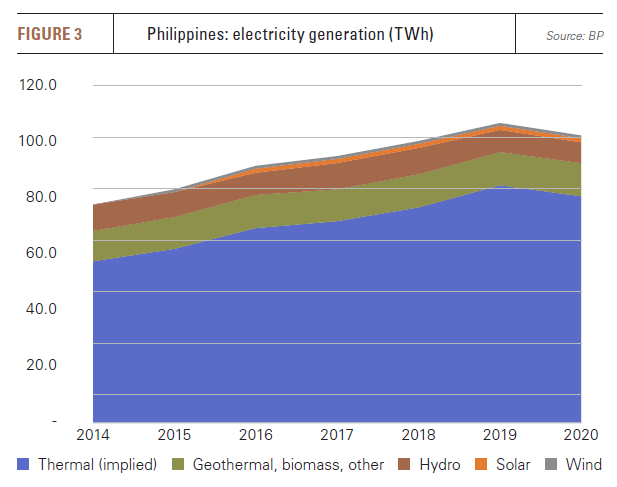

The Philippines use of renewable energy is relatively high, owing to a combination of hydro and geothermal power (see figure 2), but realising its decarbonisation plans means both a reduction in coal for power generation and an expansion of renewable energy capacities. However, renewables’ growth has been held back by lukewarm government policy, limited targets, particularly for wind, and difficulties in accessing finance. In 2020, coal made up 57.2% of total generation, compared with 19.2% for gas, 21.2% for renewables and 2.4% for oil, according to government data (see figure 3).

Electricity distribution is also problematic because the country is an archipelago comprising over 7,500 islands, making grid interconnections high in cost and difficult to build. The country is also vulnerable to adverse weather, especially typhoons.

The country’s electricity system consists of three main grids, corresponding to its three island groups: Luzon, Visayas, itself an archipelago, and Mindanao. Coal-fired generation supplies about 50% of electricity in Luzon, which is the largest grid, while gas supplies about 30%.

Visayas benefits from geothermal energy, which meets just under half of power supply, while Mindanao gets about 27% of its electricity from hydro power. Neither Visayas nor Mindanao have any gas infrastructure and both rely to a significant extent on diesel generation to meet additional and peak electricity demand, as well as provide grid stabilisation services. 70% of electricity supplied by coal is consumed on the Luzon grid, 17% in Mindanao and 13% in Visayas.

Visayas benefits from geothermal energy, which meets just under half of power supply, while Mindanao gets about 27% of its electricity from hydro power. Neither Visayas nor Mindanao have any gas infrastructure and both rely to a significant extent on diesel generation to meet additional and peak electricity demand, as well as provide grid stabilisation services. 70% of electricity supplied by coal is consumed on the Luzon grid, 17% in Mindanao and 13% in Visayas.

In addition to the possibilities for replacing baseload coal plants, this means there is significant potential for oil to LNG switching, if small-scale LNG supply chains can be established.

LNG broken down into ISO containers for distribution by ship and truck would increase throughput of the planned import terminals without requiring an increase in regasification capacity. It would allow LNG to reach small-scale, dispersed energy demand throughout the archipelago on a faster time scale and at lower capital cost than the construction of electricity lines, providing gas for generation and as cooking fuel, which would also deliver major health benefits.