Country focus: United Kingdom [LNG Condensed]

Further out, UK gas demand depends critically on the policies adopted by government to reach net zero carbon by 2050. A pathway in which carbon capture and storage plays a large role supports gas and therefore LNG demand, but other policy pathways could, in theory, eradicate natural gas use almost entirely.

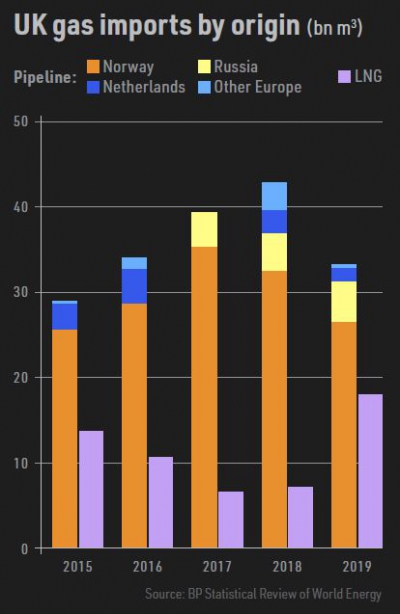

Last year, LNG imports into the UK rose 152% to 18.0bn m3, the highest level since 2011, as importers took advantage of a low-priced market to prioritise LNG over pipeline imports, which fell 22.4%. The drop in pipeline imports mainly affected Norwegian volumes, although over the last five years, UK pipeline gas imports from the Netherlands have fallen, while Russian origin imports have increased.

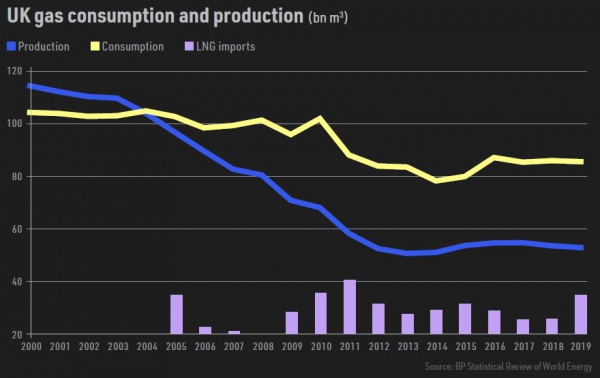

Gas demand has stayed relatively stable since 2016 at just under 80bn m3, following an increase in the period 2014-2016, which largely reflected the introduction of the UK’s carbon price floor in 2013. This raised the cost of carbon dioxide emissions from power generation above those of the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS), favouring gas over coal burn. ETS carbon allowance prices remained low because of a huge structural surplus of allowances in the European system.

The carbon price floor was followed by a decision to phase out coal-fired generation by 2025, which was subsequently brought forward to October 1, 2024. In fact, the looming deadline has prompted the early closure of many of the UK’s coal-fired plants and a sharp drop in the utilisation rate of those remaining in service. From 142.8 TWh in 2012, coal-fired generation last year in the UK had shrunk to just 6.9 TWh. The deficit left by coal’s exit has been picked up by large increases in renewable energy generation, notably wind power, and additional gas burn.

Rising import dependency

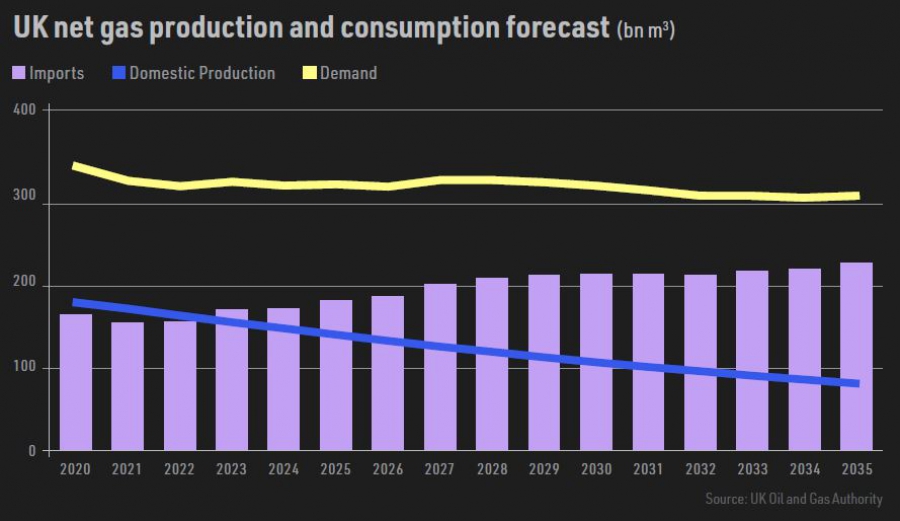

According to projections made by the UK’s Oil and Gas Authority, net gas demand, which does not include oil and gas producers’ own use, will decline over the next 15 years, from 68.6bn m3 last year to 59.7bn m3 in 2035. However, domestic production will drop from 35.4bn m3 to just 15.6bn m3, leading to a rise in imported gas volumes from 33.3bn m3 to 41.2bn m3.

A key question is whether this gas finds its way into the UK as LNG or via pipelines from continental Europe. This question will largely be determined by price, owing to the UK’s well developed gas market and large import capacities for both pipeline gas and LNG.

There is also at least the possibility that, as continental Europe also sees an increase in its dependence on gas imports – hastened by the phase out of gas production from the Netherlands’ giant Groningen field – LNG landing in the UK could flow to the continent at some times of the year.

The UK gas system will also have to supply more gas to Ireland, via interconnectors running to both the Republic of Ireland and to Northern Ireland, owing to the closure of the Kinsale gas field in July. This leaves the island of Ireland with only one gas producing asset, Corrib, which is expected to be depleted within about 10 years. Corrib currently meets about two-thirds of the Irish Republic’s gas demand, which last year amounted to 5.3bn m3. Plans for LNG terminals in the Republic of Ireland do not appear to have the support of the current government there, although there is the possibility of offsetting some gas demand -- about 1bn m3/yr, according to oil company Providence -- if the Ballyroe field is developed.

Import capacity

The UK has substantial gas import capacity compared with demand. There are four pipelines connecting the UK to Belgium, the Netherlands and Norway, which together have import capacity of 81bn m3/yr. Two, the 16.5 bn m3/yr BBL pipe to the Netherlands and the 26.9bn m3/yr IUK pipe to Belgium, have reverse flow capacity -- 5.5bn m3/yr and 21.8bn m3/yr in export mode respectively.

In addition, the country has three LNG import terminals – Grain LNG, South Hook and Dragon LNG -- with total import capacity of 51.8bn m3/yr. Grain LNG was commissioned in 2005 and has capacity of 20.4bn m3/yr, and there are plans to expand the terminal by 2025. South Hook (21.2bn m3/yr) and Dragon LNG (10.2bn m3/yr) both started up in 2009.

Net zero

However, the biggest factor governing future UK gas demand, and therefore imports, is how the country meets its commitment to reach net zero carbon by 2050, a goal adopted by the former administration of Theresa May and endorsed by the current government led by Boris Johnson.

Unabated gas burn in power generation is incompatible with net zero without huge amounts of carbon offsets and negative emissions technologies, so clean energy generation will have to rise, yet greater electrification in the heating sector and in transport as part of the country’s sectoral decarbonisation efforts also implies increased pressure on the electricity system.

The government has set ambitious renewable energy targets, notably 40 GW of offshore wind by 2030, and has reversed a previous moratorium on support for new onshore wind development. According to research by consultants Aurora Energy Research, the offshore wind target would require capital investment of nearly £50bn and the commissioning of 30 GW of new capacity in the 2020s.

The government also has a commitment to building new nuclear power stations, but this process is proving slow and uncertain, owing to the huge upfront capital cost of new nuclear plant. On current new build plans, the overall size of the UK’s aging nuclear fleet will continue to decline rather than grow.

At present, there is a significant policy gap between the UK’s decarbonisation targets and current policies in place, particularly with regard to heating, which is gas-fired in about 80% of UK homes. The government will need to formulate policies on carbon capture and storage (CCS) and hydrogen use to address these issues.

The UK is well placed with regard to both in terms of its on and offshore wind resource and the availability of CO2 storage sites in depleted gas fields in the North Sea.

CCS critical to LNG demand

Most hydrogen strategies – those adopted by the Netherlands, Germany and the EU this year, as well as studies conducted in the UK, such as Aurora Energy’s Hydrogen for a net zero GB: an integrated energy market perspective – suggest at least an interim period in which bulk hydrogen production comes from natural gas with CCS, while both renewable energy and electrolyser capacity are built up to the requisite scale.

In July, the UK’s transmission system operator National Grid ESO published its 2020 Future Energy Scenarios, which outlined various possible paths to net zero by 2050. In its most rapid energy transition scenario, ‘Leading the Way’, UK gas imports fall to 33.1bn m3 in 2030 to zero in 2050. In contrast, under the other scenarios, UK gas imports would rise to 51.6bn m3 in 2030 and under its System Transformation pathway to 67.7 bn m3 in 2050.

Gas’s future role in a net zero carbon energy system hinges on CCS – either as feedstock for the production of ‘blue’ hydrogen, or for abated electricity generation. Almost all this gas will be imported, owing to the decline in domestic gas production. In the National Grid ESO scenarios, renewable gas makes little contribution to grid gas supply as it is needed, again in combination with CCS, to deliver negative emissions and will be used for power generation at the point of production.

_f900x518_1602085883.JPG)