Country Profile: Oman seeks resilience [Gas in Transition]

For countries heavily dependent on oil and gas revenues, 2020 was a bad year on many fronts. Not only having to deal with the ravages of COVID-19, the economic impact of the huge drop in global oil demand took a massive toll on state finances. Spot oil prices for Brent averaged $41.84/barrel, the lowest since 2004, and spot prices for LNG slumped to record lows.

Moreover, Oman’s finances did not start from a strong position. In 2020, the country’s budget deficit rose to 18% of GDP, while its debt-to-GDP ratio climbed to 79%, up from 60% in 2019.

As a result, the country faces a number of challenges: a need for fiscal consolidation, maintenance of oil and gas investment at least in the short to medium term, and economic diversification, not just to address the country’s long-standing dependence on oil and gas revenues, but to meet the demands of a changing world ever more focused on limiting hydrocarbon use.

Fortunes rise

This year has at least brought higher oil and LNG prices, easing immediate fiscal concerns and offering the opportunity to make investments critical for the country’s future.

A medium-term fiscal plan, initiated by Sultan Haitham bin Tariq in 2020, focuses on fiscal consolidation and, along with higher oil prices, is expected to bring the country’s rising debt levels under control. However, ratings agencies continue to warn that neither the government’s revenues nor the overall economy have yet achieved significant diversification and that external debt financing in the next few years remains challenging.

Major investment spending is still going into the oil value chain, for example with development of the Duqm refinery. However, Oman is now also reaping the benefits of investments made over the previous five years in its gas sector, and has managed to attract considerable interest in its hydrogen potential, both blue and green. This interest bodes well for the future as the country looks to gases rather than liquids for new investment.

Gas output to sustain LNG exports

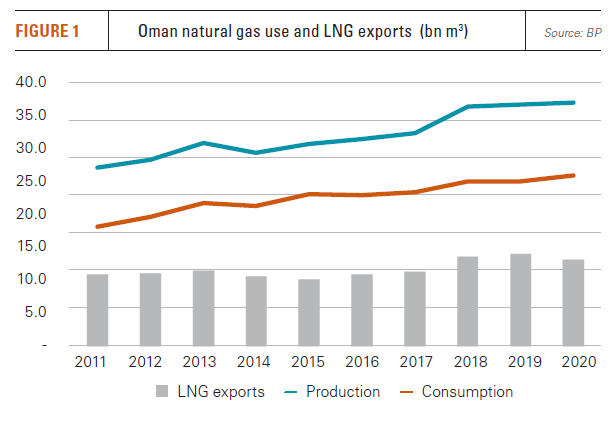

LNG exports play a smaller role than liquids in the state’s finances, but represent a potential area of growth. In addition, gas plays a critical role in powering the domestic economy. Almost all of the country’s power is generated by gas-fired power plants and domestic production has at times had to be supported by gas imports from Qatar via the Dolphin pipeline, which runs through the UAE.

Sustaining gas production is therefore key both for the domestic economy and to maximise the country’s LNG exports.

Having stalled from 2013-2016, Oman’s gas production took a jump higher in 2017 when first gas from the Khazzan tight, sour gas field, developed by BP, came on stream (see figure 1). This year has seen another step-up, with increasing gas output from the second phase of Khazzan, known as Ghazeer. According to Oman’s National Centre for Statistical Information (NCSI), January-September gas output reached 37.95bn ft3, up 11.8% from the same period last year.

The rise in domestic gas production has been accompanied by rising LNG exports. The first two trains at Oman LNG were completed in 2000 with nameplate capacity of 7.1mn mt/yr. A third train was completed in 2006, adding 3.3mn mt/yr of capacity. Oman LNG has been undergoing an extensive process of de-bottlenecking, which, despite a dip last year, and some production problems this year with Train 1, should see LNG output return to the 2019 record level of 14.1bn m3, sustained by feedstock gas from the country’s sour gas developments.

Sour gas development

Despite its complexity and cost, sour gas deposits are largely underpinning Oman’s role as a gas exporter.

Khazzan was discovered in 2000, but was not developed until 2014, with the second phase reaching financial sanction in 2018. The field, which lies in the south of Block 61 in the Ad Dhahirah governorate, has proven gas and condensate reserves of 100 trillion ft3, of which 10 trillion ft3 are recoverable. The size of the field suggests at peak it will be able to meet a third of the country’s gas demand.

Phase one consisted of 50 wells, but eventually the drilling programme could stretch to more than 300, predominantly horizontal wells, to access gas from the field’s tight rock formations. Phase 1 produces 1 bn ft3/d of gas and 35,000 b/d of condensate, while Ghazeer, which saw first gas in October 2020, ahead of schedule, adds 0.5bn ft3/d plus 15,000 b/d of condensates.

State-owned oil and gas company Petroleum Development Oman (PDO), which announced the discovery of a tight gas field with estimated recoverable gas reserves of over 4 trillion ft3 and 112mn barrels of condensate in 2018, has also been adding production. First production from its sour gas Yibul Khuff project started up in September. When up to full capacity, the project is expected to produce 20,000 b/d of crude oil and 1.8bn m3/yr of gas.

Gaseous future

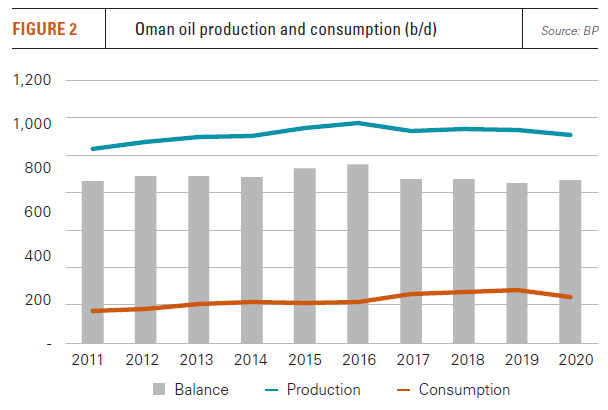

In contrast, oil production peaked in 2016 at just over 1mn b/d. Oil output has declined slowly since then (see figure 2). Oman has supported investment in innovative enhanced oil recovery processes which have limited the decline, and daily liquids production is expected to move back above 1mn b/d over the country’s current five-year plan, 2021-2025.

However, ultimately decline from its mature oilfields is inevitable and, although sizeable, Oman does not have the massive proven oil reserves of some of its Gulf neighbours.

Sustaining liquids output also takes a toll on the gas sector as gas is reinjected into oil fields to maintain pressure. The NCSI data for September showed that oilfield injection consumed 9.81bn ft3 of gas in September, up 21.3% from September 2020.

Oman’s oil and gas developments to date have been largely onshore, but it is now exploring more actively the offshore. Currently, there are only two offshore sites in production, Block 8 and the more recently commissioned Yumna field. Block 23 off the Sultanate’s east coast has been offered in a new exploration round. Italian major Eni drilled the country’s first deepwater well on block 52 in 2020 and although reportedly unsuccessful, it intends to drill a second next year. However, unless the offshore yields some major oil finds, Oman’s hydrocarbon output is set to become ever more gaseous.

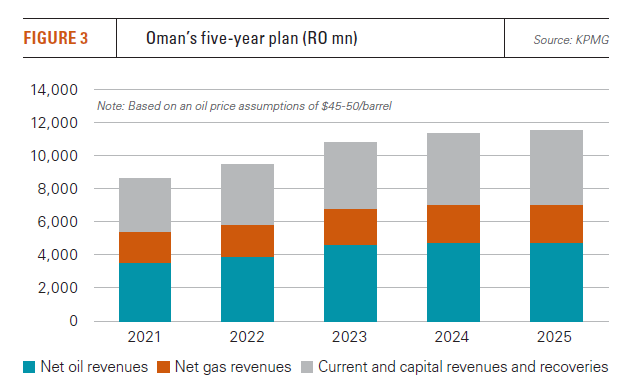

Consultants Rystad Energy forecast that owing to oil output declines and new investment in gas fields, by 2025, gas will make up more than 50% of the country’s hydrocarbon output. The five-year plan anticipates gas contributing 20% of state revenues as against 42% for oil (see figure 3).

Hydrogen pathway

As with other Middle Eastern states, renewable energy offers an opportunity to free up gas used domestically for export. Oman has set a target of generating 30% of its electricity from renewables by 2030, more than two-thirds of which is expected to come from solar power. Other countries in the region, for example the UAE and Saudi Arabia, have already started to capitalise on the Middle East’s abundant sunshine, receiving world-beating low bids for generation, and there seems no reason why Oman cannot do the same.

Freeing up gas for export opens a number of possibilities. One is to further expand the country’s LNG facilities, another is to combine gas production with carbon capture and storage (CCS) to produce blue hydrogen. However, Oman has also been very successful in generating interest in green hydrogen, a development which fits well with its Vision 2040, a long-term strategy to promote economic diversification and resilience.

There has been a boom in announced hydrogen/ammonia projects in the last six months.

In August, Oman signed a land allocation deal for a green hydrogen and ammonia plant to be located at Duqm port. The project is expected eventually to comprise 3 GW of solar power and 500 MW of wind to produce 900,000 metric tons/yr of ammonia.

Only a few months earlier, state-owned energy firm OQ announced plans for the country’s first green hydrogen project in partnership with Hong Kong’s InterContinental Energy and Kuwait’s Enertech. This too will use a combination of wind and solar power to generate 1.8mn mt/yr of hydrogen and up to 10mn mt/yr of ammonia. Start-up is expected in 2026.

German utility Uniper and Belgium’s DEME have announced plans for Hyport Duqm. This envisages a 1.3-GW wind and solar-powered hydrogen/ammonia facility. Meanwhile OQ, Linde and the Dubai Transport Co. have unveiled a project near the city of Salalah for a hydrogen/ammonia plant backed by 400 MW of renewable energy.

German utility Uniper and Belgium’s DEME have announced plans for Hyport Duqm. This envisages a 1.3-GW wind and solar-powered hydrogen/ammonia facility. Meanwhile OQ, Linde and the Dubai Transport Co. have unveiled a project near the city of Salalah for a hydrogen/ammonia plant backed by 400 MW of renewable energy.

These projects are part of the Ministry of Energy and Minerals’ national hydrogen alliance, which is designed to secure Oman a role in emerging hydrogen markets in line with the Sultanate’s Vision 2040. According to Energy Renewal, a unit of PDO, blue and green hydrogen potential in the country is about 1 GW by 2025, 10 GW by 2030 and 30 GW by 2040.

The 2021 budget, based on an average $45/barrel oil price, sets as a priority economic diversification and stimulating the private sector. The country’s five-year plan aims for foreign direct investment in the oil and non-oil sectors to reach 10% of GDP. In effect, Oman has declared itself open for business in both its traditional sectors and establishing a viable new role in the energy transition.