Crunch time for LNG [NGW Magazine]

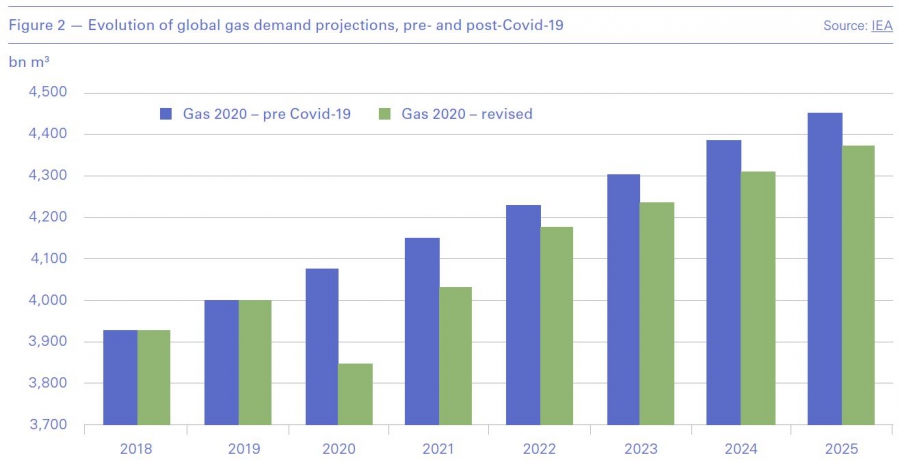

A number of reports by International Energy Agency (IEA), Oxford Institute of Energy Studies (OIES) and others over the last few months have pointed out that new gas liquefaction projects in pre-construction development globally face delays or even cancellations owing to the oversupplied and challenging LNG markets and rock-bottom prices (Figure 1).

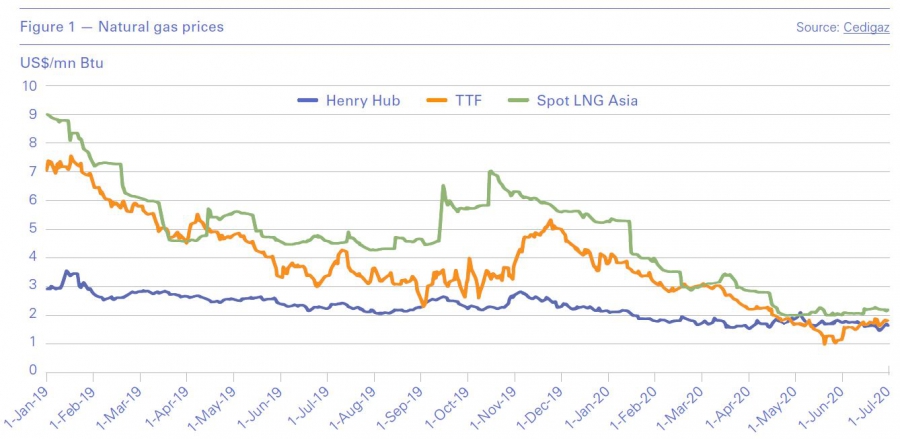

Gas prices are very low – unprofitable and unsustainable – and look likely to remain low for the next few years owing to continuing overcapacity, even as overall gas demand is expected to start recovering and to continue rising (Figure 2).

The IEA states in its ‘Gas 2020’ report that “FIDs taken in the recent years lead to a strong uptick in LNG liquefaction projects, which is expected to add up to 120bn m³/y of export capacity between 2020 and 2025 – or an increase of 20%.”

Indeed, from April 2019 to May 2020, global LNG export capacity grew by 6%, from about 416mn metric tons (mt)/yr to 442mn mt/yr. Over the same period, based on optimistic forecasts that demand will exceed LNG supply by 2022 to 2024, the amount of LNG export capacity under construction surged from about 45mn mt/yr to over 120mn mt/yr, driven by North America.

In addition to reduced gas demand this year, what has been problematic was the enthusiastic, unconstrained, build-out of new liquefaction plants in the US, possibly encouraged by the ‘America first’ policy. This has contributed to the oversupply of LNG, much the same way as shale oil did to global oil supplies, leading to a price collapse. This has now been pushed back as are plans for more FIDs in 2020.

A webinar survey taken during an event organized by Singapore International Energy Week had about half the sample expecting between zero and five final investment decisions next year.

Normally this herd-like behaviour would simply show the disconnect between the reality and the adage that “gas is a long-term business.” But this time it is different as the imbalance is seen persisting until the middle of the decade at least, and nobody wants to bring on a new train in a buyer’s market.

And so investment decisions for proposed liquefied natural gas export terminals have been delayed or cancelled this year in Australia, Mozambique, Qatar, Mauritania, Senegal and the US.

Following the European Investment Bank’s (EIB) decision to stop funding fossil fuel projects after the end of 2021, including natural gas projects, EIB’s vice-president, Andrew McDowell, told Reuters: “Investing in new fossil fuel infrastructure like liquefied natural gas terminals is increasingly an economically unsound decision.”

There is simply too much gas chasing limited demand globally and this may last well into the foreseeable future, putting LNG under increasing pressure. A rebound is expected in 2021, but it is not likely to lead to a rapid return to pre-crisis levels.

This is also the view of the IEA in its Gas 2020 report. It points out that “slower growth in gas demand post-2020 results in liquefaction capacity additions outpacing incremental LNG import through 2025, thus limiting the risk of a tight LNG market over the forecast period.”

IEA executive director Fatih Birol warned: “Global gas demand is expected to gradually recover in the next two years, but this does not mean it will quickly go back to business as usual…. The Covid-19 crisis will have a lasting impact on future market developments, dampening growth rates and increasing uncertainties.”

This is especially so, as future LNG demand growth, widely assumed to be led by China and India, may be less than expected. For economic reasons and security of supply concerns both countries are giving priority to maximising energy production from domestic resources, including from coal, at the expense of imports.

But, despite the challenging times and low prices, Qatar and Russia are accelerating their projects to lock-in future market share.

Even though the LNG market is facing difficulties, it does not mean that its future is grim. Natural gas has a long-term role to play, particularly in Asia supporting growth in energy demand, but also in Europe supporting clean energy deployment.

LNG future in Europe

In the short to medium term the future of LNG in Europe looks good. But beyond that the messages are mixed. The first is EIB’s decision not to fund and gas projects beyond the end of 2021, including new LNG import/regasification terminals. EIB’s McDowell said “From both a policy and from a banking perspective, it makes no sense for us to continue to invest in 20 to 25-year assets that are going to be over-taken by new technologies and do not deliver on the EU’s very ambitious climate and energy targets.”

The European Green Deal (EGD) has set the course for a decarbonised Europe by 2050, in which, approaching 2030 and beyond, the use of unabated gas is expected to start diminishing.

Europe’s newly released hydrogen strategy has made a decisive turn away from blue hydrogen – produced from conversion of natural gas – to green hydrogen. But, then, it kept the door open for blue hydrogen during the transition period, without defining what this means. Frans Timmermans, vice-president European Commission (EC), acknowledged that “natural gas will, for a while, play the role of a transitional energy.”

More recently, with the support of the EC, member states agreed that the EU’s recovery package should exclude nuclear and fossil fuels projects, including natural gas. But on July 6 the European parliament opened the door, when it called for rules that could allow some of the ‘Just Transition Fund’ money to be spent on natural gas projects. However, this still has to be approved by EU member states.

Nevertheless, despite these mixed messages, there is support for the view that natural gas will have a role to play in the EU during the energy transition period. Given a recent report by the IEA warning that, unless hugely accelerated, clean energy innovation will not deliver net-zero emissions by 2050, the transition period for natural gas in the EU could last another 20 to 30 years. This will be further reinforced if EU member state governments concentrate on economic recovery post-Covid-19, rather than faster implementation of clean energy measures – something that so far looks quite likely.

Following a marathon meeting lasting four days, EU leaders agreed July 21 a landmark spending package to rescue their economies from the impact of Covid-19. But after many compromises to reach a deal, the size of some of the more progressive elements originally proposed by the EC, including research and innovation spending and the Just Transition Fund, was scaled back.

Even though almost a third of the approved package is earmarked for climate action, it is up to EU member states to decide how to allocate the money, albeit with some oversight by the EC. That will keep the debate for use of natural gas going, at least during the transition phase.

Greens in the European Parliament were not happy with the deal, saying that “this agreement is at the expense of the climate,” warning that it lacks climate spending accountability.

US natural gas and LNG

A Council of Foreign Relations (CFR) headline July 2 reads: “US natural gas: once full of promise, now in retreat.” This completely sums up the current challenging situation.

Even the UK business daily Financial Times (FT) is asking if the party is finally over for US oil and gas, adding that cancelled pipelines and green ambitions point to a declining role for gas in the energy mix.

Important decisions by a federal court on July 9 suspending the use of the Dakota access pipeline and by the Supreme Court on July 7 blocking a permit for construction of the Keystone XL pipeline, as well as the cancellation of a third major pipeline on July 5, have made it harder to bring oil and gas to market. Coupled with over 200 bankruptcies in the shale sector, including the high profile Chesapeake Energy failure, the future of ever-increasing shale oil and gas production in the US suddenly looks bleak.

This also threatens the continuing growth of cheap associated gas supplies, which is so key to the competitiveness of US LNG, at a time of global price sensitivity.

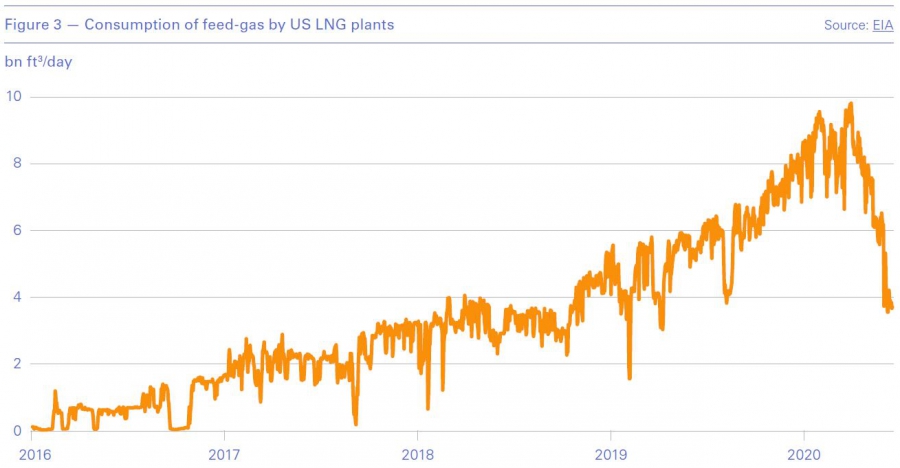

The world was experiencing an oversupply of LNG before Covid-19, but the impact of the pandemic on demand, both in the US and globally, has exacerbated the problem. Prices are rock-bottom, with Henry Hub spot prices going as low as $1.63/mn Btu in June. In addition, US LNG exports and deliveries of feed-gas to US LNG plants have plummeted (Figure 3). The Energy Information Administration (EIA) expects US LNG exports to drop to a quarter of capacity in July and August. Even worse, analysts at US energy specialists Simmons Energy project that “US LNG utilisation will hover between 60% to 70% over the next several years.”

In the longer term the challenge for US LNG will come from cheaper Qatar LNG, as well as Russian pipeline gas and LNG.

As a result, US LNG projects that have already achieved FID, or were planning to, are now being delayed to 2021 and beyond, awaiting market recovery. These include Tellurian’s Driftwood LNG, Sempra Energy’s Port Arthur project and Texas LNG terminal at Brownsville. Cheniere is delaying FID on its expansion project at Corpus Christi and Anglo-Dutch Shell pulled out of the Lake Charles project. The promising future of US LNG, forecast in 2019, now looks highly unlikely.

This is bad news for shale gas producers, especially as US domestic gas demand is expected to decline further due to the inexorable increase in renewable energy. US utilities are now planning renewable power generation, backed up by battery storage, to replace coal-fired plants, without the need for gas-fired peaker plants. The EIA forecasts that US gas demand will drop down to less than 79bn ft³/d in 2021, in comparison with 85bn ft³/d in 2019.

Use of renewables in the US’ energy mix is accelerating, driven by low costs, but also increasingly backed up by investors keen on clean energy. Politicians are also jumping onto the clean energy bandwagon, such that a change in November’s presidential elections is likely to accelerate transition to green causes even further. Ominously, the FT concludes that “American energy dominance in future will depend less on oil and gas.”

But before writing shale completely off, one should ask ExxonMobil and Chevron. They still have faith in US shale, and demonstrate this through their investments. Chevron’s takeover of Noble Energy, announced July 21, mostly because of its shale assets in the oil-rich Permian Basin in Texas and the DJ Basin in Colorado, has restored faith and has given the shale sector new hope.

Environmental impact

There is growing concern about the role of methane emissions in the LNG industry, with experts warning that “an LNG project has significantly higher emissions than a typical pipeline gas counterpart.” The OIES recommends that “although yet to be addressed by most LNG projects, [decarbonisation] should be very much on the radar of new project developers.”

Proponents of LNG argue that it will help wean importing countries off coal, lowering carbon emissions and improving air quality. However, methane emissions along the entire chain of producing, transporting, liquefying, shipping and exporting LNG put this into question, something that appears to be particularly acute with US shale gas.

The EU’s forthcoming methane emissions reduction strategy “would force natural gas producing regions across the globe to seriously tackle the issue – if they want to continue to supply the EU.” However, this is not likely to be the case in Asia where most future growth in LNG demand is expected.

Risks to new LNG projects are also coming from commitments to address greenhouse gas emissions. Ever-increasing future LNG demand from European international oil companies (IOCs) committing to net-zero emissions by 2050, such as BP, may be in question. As are forecasts of continuously and rapidly increasing LNG demand well into the future, ignoring the likely impact of a global shift toward carbon neutrality.

Long term concerns about climate change increase pressure on gas and LNG and make the industry’s emergence out of this crisis even more challenging – tackling of methane emissions is imperative to the future of the industry.

Challenges

Warnings from the UN Environmental Programme (UNEP) in a 2019 report may be coming home to roost, especially for US LNG. It said “Many countries appear to be banking on export markets to justify major increases in production. The net result could be significant over-investment, increasing the risk of stranded assets, workers, and communities, as well as locking-in a higher emissions trajectory.”

This may be creating an over-capacity balloon that could burst if the outlook for LNG does not improve significantly. This is echoed by the IEA. It states that “slower growth in natural gas demand is likely to weight on average utilisation rates of liquefaction plants, creating a situation of overcapacity as liquefaction growth outpaces incremental LNG trade.” The industry needs to overcome a combination of challenges: overbuilding, low prices, pandemic disruptions and increasing environmental opposition.

Not only does gas face an increasing challenge from renewables combined with battery storage; worsening global political polarisation is making countries more wary of relying on energy imports, increasing reliance on domestic energy resources at the expense of imports.

Another challenge comes from Russia. Gazprom and its partners are considering increasing the capacity of the Power of Siberia gas pipeline from 38bn m³/yr now to 44bn m³/yr. Gazprom has also begun to design a second, 50bn m³/yr, gas pipeline to China through Mongolia, already called Power of Siberia-2. Alexei Miller, CEO Gazprom, said on June 26, on the occasion of the company’s annual general meeting, that there is potential for Russian pipeline gas export capacity to China to reach more than 130bn m³/yr in the future with the addition of more routes. Given the worsening US-China political situation, pushing China and Russia closer together, this may gain traction. As well as providing a balance to the potential decline of gas exports to Europe, it will limit China’s future LNG import demand.

All IOCs have cut their 2020 capital spending budgets dramatically and are shedding tens of thousands of staff. Further cuts are expected, with the total likely to range between 40% to 60% by the end of 2020, with more to come in 2021. This, and commercial concerns due to low prices, are likely to limit the ability and appetite of IOCs to invest in new LNG projects over the next few years.

Gas liquefaction projects require large investments. Uncertainties about future markets and prices, combined with prolonged oversupply, make sanctioning of such investments more challenging. Inevitably, in the short to medium future LNG will be facing a crunch time.

_f1920x300q80.jpg)