Decarbonising European industry – is it possible? How will it affect natural gas? [Gas Transitions]

Climate policy in the EU has so far focused mostly on the power generation and transport sectors. Heavy industry – which accounts for about 14% of Europe’s greenhouse gas emissions and 20% of global emissions – has flown pretty much under the radar. European industry does fall under the EU Emission Trading System (ETS) and as such does have emission reduction targets. But the EU member states have protected their industries with a lot of exemptions and free emission permits within the ETS, so that there has been little incentive for companies to cut their emissions.

In a report published earlier this month (“Cracking Europe’s hardest climate nut – how to kick-start the zero-carbon transition of energy-intensive industries”), NGO Carbon Market Watch notes that “carbon pollution from heavy industry has not decreased since 2012 and is not predicted to do so until 2030.”

“Under the EU ETS”, says Carbon Market Watch, “energy-intensive industries receive too many free emission allowances which allows them to make substantial profits from the system that is meant to make polluters pay. With virtually no market incentive, most energy-intensive industries are not strongly committed to investing in cleaner technologies and to making the necessary changes to decarbonise. In fact, the current long-term roadmaps presented by the industries themselves, if taken together, represent a mere 18% reduction of greenhouse gas emissions between 2016 and 2050.”

Mounting pressure

Nevertheless, pressure is mounting on industry in Europe to take more action to limit its carbon emissions. As climate think tank European Climate Foundation (ECF) points out, “the long-term strategy, A Clean Planet for All, published by the European Commission last November, broke new ground by including all sectors of the economy towards net-zero emissions and considering pathways that eliminate nearly all emissions from industry.”

In December 2018, 18 member states, the “Friends of Industry” called on EU decision makers to “act quickly to maintain European industry’s competitiveness, while taking into account the energy transition to a safe, sustainable and low-carbon and circular economy and the digital transformation of the industry.” On March 22 this year, member states called on the European Commission to present by the end of 2019, a long-term vision for the EU’s industrial future, with concrete measures to implement it.

In this context, ECF commissioned two groups of researchers – from Material Economics in Stockholm and the Institute of European Studies (IES) in Brussels – to outline possible “pathways” showing how European industry might be “decarbonised” by 2050.

The reports, both published under the name Industrial Transformation 2050, Pathways to Net-Zero Emissions from EU Heavy Industry, conclude that “achieving net-zero emissions for European energy-intensive industries by 2050 at the latest is technically and economically possible and multiple pathways can get them there.”

Industrial gas demand

Before we take a further look at these “pathways,” let’s see how the “decarbonisation” of industry would affect gas demand. Industry is obviously an important consumer of natural gas. According to the IEA’s World Energy Outlook 2018, globally 25% of gas demand comes from the industrial sector.

Interestingly, under the IEA’s Sustainable Development Scenario, the share of industry in gas demand will grow to over 29% in 2040. In the IEA’s other, “non-sustainable” scenarios, the share of industry will be limited to around 26% in 2040.

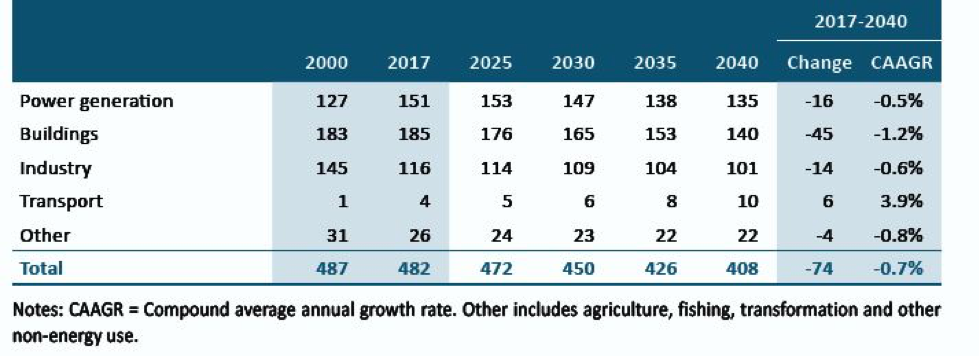

In other words, the result of climate policy will be to make industry relatively more important as a source of gas demand in future. This is because decarbonisation will impact gas demand in the power sector even more. In the IEA’s Sustainable Development Scenario, the share of the power sector in gas demand will decline from 40.4% in 2017 to 30.2%. Industry will use almost the same amount of gas as the power sector in 2040 in this scenario, as can be seen in this table:

.png)

Global gas demand by sector under three scenarios – source WEO 2018

Looking specifically at Europe – still the world’s largest importer of natural gas – industry in 2017 accounted for 24% of gas demand. Under the IEA’s “New Policies Scenario” (which is based on the assumption that all climate policies that have been announced by countries to date will be implemented, but the Paris climate targets will not be reached) industrial gas demand in Europe will decline by 0.6% per year to 2040, but the market share of industry in the gas market will remain largely unchanged, as shown in this table:

Natural gas demand in the EU in the “New Policies Scenario” – source WEO 2018

“All energy-intensive branches of industry see their gas demand decline slightly, largely because of economic restructuring and efficiency improvements rather than a shift to other fuels and technologies”, notes the WEO. The WEO does not spell out what the “Sustainable Development Scenario” would mean for gas demand in the industrial sector in Europe.

Different pathways

The “Industrial Transformation 2050” studies do not specifically deal with natural gas either, but it is obvious that under their decarbonisation scenarios industry in Europe would use a lot less natural gas. The report from Material Economics outlines four major ways in which industry could reduce its CO2 emissions, and in only one of them (carbon capture and storage) would natural gas still be used.

Greenhouse gas emissions from industry are around 500mn (mt)/year, notes the report, about 14% of the EU total. Industry could reduce these emissions in the following ways:

- “Increased materials efficiency” could reduce emissions by 58-171 Mt per year by 2050. The report calls the opportunities for more efficient use of materials “surprisingly wide-ranging”.

- “High-quality materials recirculation” could be good for 82-183mn mt of reductions. “By 2050, a stretch case could see 70% steel and plastics produced through recycling, directly bypassing many CO2 emissions, as steel and plastics recycling can use green electricity and hydrogen inputs.” The report notes that “Unlike most other forms of recycling, chemical recycling of plastics requires lots of energy, but is almost indispensable to closing the ‘societal carbon loop’, thus escaping the need for constant additions of fossil oil and gas feedstock that in turn becomes a major source of CO2 emissions as plastic products reach their end of life.”

- “New production processes” could contribute 143-241mn mt of reductions. “For steel, several EU companies are exploring production routes that switch from carbon to hydrogen. In cement, new cementitious materials like mechanically activated pozzolans or calcined clays offer low-CO2 alternatives to conventional clinker. For chemicals, several proven routes can be repurposed to use non-fossil feedstocks such as biomass or end-of-life plastics.” In addition, “large amounts of zero-emissions electricity will be needed, either directly or indirectly to produce hydrogen.”

- Finally, “carbon capture and storage/use” could help reduce emissions by 45-235mn mt/year, notes the report.

Unfortunately, the range for the contribution CCS might make is rather wide. What might we expect from it? The researchers caution that the application of CCUS is “challenging” in many cases:

“CCU is viable in a wider net-zero economy only in very particular circumstances, where emissions to the atmosphere are permanently avoided. CCS/U also faces challenges. In steel, the main one is to achieve high rates of carbon capture from current integrated steel plants. Doing so may require cross-sectoral coupling to use end-of-life plastic waste, or else the introduction of new processes such as direct smelting in place of today’s blast furnaces. For chemicals, it would be necessary not just to fit the core steam cracking process with carbon capture, but also to capture CO2 upstream from refining, and downstream from many hundreds of waste incineration plants. Cement production similarly takes place at around 200 geographically dispersed plants, so universal CCS is challenging. Across all sectors, CCS would require public acceptance and access to suitable transport and storage infrastructure. These considerations mean that CCS/U is far from a ‘plug and play’ solution applicable to all emissions. Still, it is required to some degree in every pathway explored in this study. High-priority areas could include cement process emissions; the production of hydrogen from natural gas [“blue hydrogen”]; the incineration of end-of-life plastics; high-temperature heat in cement kilns and crackers in the chemical industry; and potentially the use of off-gases from steel production as feedstock for chemicals."

Tomas Wyns, lead author of the report from the Institute of European Studies (IES), says in a telephone interview that “whereas not so long ago CCS was seen as the only or the major option to decarbonise industry, now there are a range of options”, and “CCS is not the most important anymore.”

Asked how decarbonisation will impact industrial gas demand in Europe, Wyns says this “will depend on the choices that will be made”, both by industry and by policymakers. “Certainly in the lighter industries, such as ceramics and glass, we expect that natural gas will be replaced by electrification of heating processes, or perhaps by biogas to some extent. For large gas users, such as ammonia producers, blue hydrogen (made from natural gas in combination with CCS) may be an option, besides green hydrogen (made from renewable power).”

Wyns also notes that natural gas could maintain an important role if industry turned to large-scale production of hydrogen from natural gas through pyrolysis, a technology that is still in its early stages. “Pyrolysis of natural gas produces hydrogen and solid carbon. This carbon could be used in other applications or buried underground. This method might be cheaper than electrolysis. You would be able to keep a fairly large amount of natural gas in the system.” Wyns points out that the region of Rotterdam-Antwerp-northern France is one of the largest users of hydrogen in the world.

Per Klevnäs, partner at Material Economics and also a lead author, notes that natural gas could also yet play a significant role as a “transition fuel”, for example, in steelmaking. “If a steelmaker like Salzgitter installs new equipment that will be fit for hydrogen-based steel production, they may well use natural gas for some time, until there is enough green hydrogen available.”

Klevnäs further notes that the assumption of the Industrial Transformation study – net-zero emission in 2050 – is very ambitious. “It goes much further than other studies in entirely eliminating unabated fossil fuel use. We did the study as a contribution to inform the discussion.”

Less dependent

So how likely is it that Europe will be able to create a net-zero-emission industry? The report from Material Economics notes that the decarbonisation of industry has an important benefit: it will reduce energy imports considerably.

According to the report, “steel, cement, plasticsand ammonia production together use 8.4 EJ of mostly imported oil, coal and natural gas. A major benefit of a more circular economy would be to reduce these needs by up to 3.1 EJ per year in 2050 through improved materials efficiency, new business models in major value chains, and large shares of materials recirculation.”

“Remaining needs”, notes the report, “would be replaced by sustainably sourced biomass (1.1–1.3 EJ), used primarily as feedstock, and large amounts of electricity (2.5–3.6 EJ), used directly or for the production of hydrogen. The remaining fossil fuels and feedstock would be as low as 0.2 EJ, though with high levels of CCS, 3.1 EJ could remain.”

All in all, note the authors, “Europe could become much less dependent on imports of inputs to its industrial production, even if some basic constituents (such as ammonia or hydrogen) were eventually to be imported.”

That’s the good news. Costs also appear to be manageable – at least from a macroeconomic point of view: “Consumer prices of cars, houses, packaged goods, etc. would increase by less than 1% to pay for more expensive materials. Overall, the additional cost of reducing emissions to zero are €40-50 billion per year by 2050, around 0.2% of projected EU GDP. The average abatement cost is €75-91/metric tonne of CO2.”

The big bottleneck, however, is the costs that the companies would have to bear. “The business-to-business impact is large”, the report admits, “and must be managed. All pathways to net-zero require the use of new low-CO2 production routes that cost 20-30% more for steel, 20-80% for cement and chemicals, and up to 115% for some of the very ‘last tonnes’ that must be cut.”

All pathways also require“an increase in capital expenditure. Whereas the baseline rate of investment in the core industrial production processes is around €4.8–5.4 billion per year, it rises by up to €5.5 billion per year in net-zero pathways, and reaches €12–14 billion per year in the 2030s. Investment in other parts of the economy also will be key, including some €5–8 billion per year in new electricity generation to meet growing industrial demand.”

The report notes quite frankly that these extra costs “cannot be borne by companies facing both internal EU and international competition, so supporting policy will be essential.”

For Tomas Wyns it is clear that under these circumstances, decarbonisation of European industry can only succeed with “an integrated European approach”. Given the high expenditures, he says, and the high risks for the companies, “they are only likely to make the transition if there is a firm EU-wide framework in place.”

|

What EU policymakers could do – over and above the ETS In a recent article for Euractiv, co-authored with Gauri Khandekar, Tomas Wyns has three suggestions for policymakers on how to make major emission reductions in industry possible:

|

|

“German industry ready for deep decarbonisation, but laments policy lag” “German industry heavyweights including chemical maker BASF, HeidelbergCement, gas supplier Linde and steelmaker Salzgitter say they are prepared for profound emissions cuts, but still lack the necessary market signal from policymakers”, reported website Clean Energy Wire (CEW) earlier this month. Industry was responsible for nearly a quarter of Germany’s total greenhouse gas emissions in 2018, notes CEW. It will have to cut CO2 output by 25 percent over the next ten years to reach its official 2030 climate target. Last year, Germany’s industry lobby organisation BDI published a study, “Climate Paths for Germany”, which turned out to be surprisingly optimistic about the possibility for the German energy-intensive industry to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions. The in-depth study, which involved 70 companies and associations as well as “a board of renowned economists”, concluded that 80% emission reduction was “technically feasible” and even “macroeconomically viable”. Like the “Industrial Transformation 2050” study discussed above, the BDI research concluded that one key driver of macroeconomic advantage was a decline of 70% of fossil fuel imports. In addition, “most industries would benefit from increasing national value creation, for example, construction, electronics, part of the energy sector, and mechanical and plant engineering”. BDI said that “Successful efforts to tackle climate change would trigger extensive modernization activities in all sectors of the German economy and could furthermore open up opportunities to German exporters in growing clean technology markets. Studies suggest that the global market volume of key climate technologies will grow to €1 trillion to 2 trillion per year by 2030. German companies can solidify their technological position in this global growth market.” With regard to CCS, BDI said that “As long as possible alternatives do not become significantly cheaper, CCS technology would be required to eliminate process emissions in steel and cement production, steam reforming, as well as emissions from remaining refineries and waste incineration plants. To achieve this, serious acceptance issues would need to be overcome.” However, the study did contain cautionary notes. It said that achieving 95% emission reductions would only be feasible if other major economies would be similarly ambitious. And even the 80% emission reduction scenario was based on what it called “ideal implementation”. That is to say, the report assumed “optimisation across sectors and right decisions being made at the right time. Mismanaging the implementation (think of excessive feed-in tariffs and delayed grid expansion in case of Germany’s Energiewende) could considerably increase costs and risks or even render the goal unattainable.” More than a year later, German industry representatives still say that ambitious reductions are possible, but they also pointed out, as Clean Energy Wire writes, that “existing polices are blocking the massive investments necessary for deep industry decarbonisation.” At a conference in Berlin, industry representatives pointed out that many of the easiest steps to lower emissions, for example by increasing energy efficiency, “have already been implemented. The next step for many companies will be much more difficult and costly: changing the core processes at the heart of their businesses. This could include replacing fossil fuels used in many chemical processes with hydrogen made using renewable electricity.” But they noted that “green hydrogen” is currently twice as expensive as natural gas, so “the government must find a way to make the technology commercially viable.” Many of the industry spokesmen pointed out that in the current situation, industry is not likely to make the investments needed to decarbonise its production processes. For example, Heidelberg Cement public affairs manager Christoph Reißfelder noted that “carbon-neutral cement is technologically possible by 2050”, but added that “the framework conditions are not right for it.” Jens Waldeck, who heads Linde Gas’ operations in Central Europe, was quoted as saying that “an overhaul of taxes and levies is needed to enable breakthrough technologies.” Many other participants also highlighted the importance of paving the way for a ‘hydrogen economy’ currently blocked by relatively high power prices, reported Clean Energy Wire. “Executives called for reducing taxes and levies on electricity to make low-carbon technology more competitive.” As an example, the article mentions steelmaker Salzgitter’s proposal to replace carbon-based fuels with renewable hydrogen in metallurgy, a project dubbed SALCOS (Salzgitter Low CO2 Steelmaking). “We can only realise the SALCOS project if we can make sure that we will be able to sell our low-carbon steel afterwards”, the company’s head of corporate technology Volker Hille told Clean Energy Wire. “The first stage of SALCOS alone will require an investment of about €1.3 billion in new plant equipment, illustrating the need of substantial public funding.” There is even a risk that in the current uncertain political climate, the industry could stop investing altogether, noted Patrick Graichen, head of energy think tank Agora Energiewende. He warned that “energy-intensive companies have slashed their capital expenditures as they have realised that conventional technologies with a high CO2 output are no longer sustainable and could turn into stranded assets, while innovative low-carbon concepts are not yet profitable.” |

How will the gas industry evolve in the low-carbon world of the future? Will natural gas be a bridge or a destination? Could it become the foundation of a global hydrogen economy, in combination with CCS? How big will “green” hydrogen and biogas become? What will be the role of LNG and bio-LNG in transport?

From his home country The Netherlands, a long-time gas exporting country that has recently embarked on an unprecedented transition away from gas, independent energy journalist, analyst and moderator Karel Beckman reports on the climate and technological challenges facing the gas industry.

As former editor-in-chief and founder of two international energy websites (Energy Post and European Energy Review) and former journalist at the premier Dutch financial newspaper Financieele Dagblad, Karel has earned a great reputation as being amongst the first to focus on energy transition trends and the connections between markets, policies and technologies. For Natural Gas World he will be reporting on the Dutch and wider International gas transition on a weekly basis.

Send your comments to karel.beckman@naturalgasworld.com