Dieter Helm on gas, the energy crisis and war [Gas in Transition]

The following is based on a compelling presentation by Professor Dieter Helm at the FLAME Gas & LNG conference held in Amsterdam on May 3-5. He questioned the outcome of COP26, analysed what the Ukraine war and the energy crisis really mean, how important gas is to the net-zero goals and made suggestions on what should happen next.

Recovery from COVID-19 and quantitative easing led to the global commodity boom, increasing energy demand and the high prices we are experiencing now. The Ukraine war exacerbated that, but also brought home the enduring importance of fossil fuels, global energy security and energy affordability.

COP26 and the rest

The big question is climate change and how far the world is down the road of energy transition.

COP26 did not provide the answers. It mostly addressed reduction of energy production emissions, but failed to address the erosion of sequestration in geography - the storage of CO2 in vegetation such as grasslands or forests, as well as in soils, peats and oceans.

The world’s natural systems can absorb huge amounts of carbon, but with people doing so much damage to the natural world, they are not working as they should.

Climate change is caused by increases in carbon concentration in the atmosphere. But the Paris Agreement NDCs are defined in terms of limiting production emissions, i.e. those produced within a country's territorial boundaries but do not include imports and no account is taken of deteriorating natural sequestration.

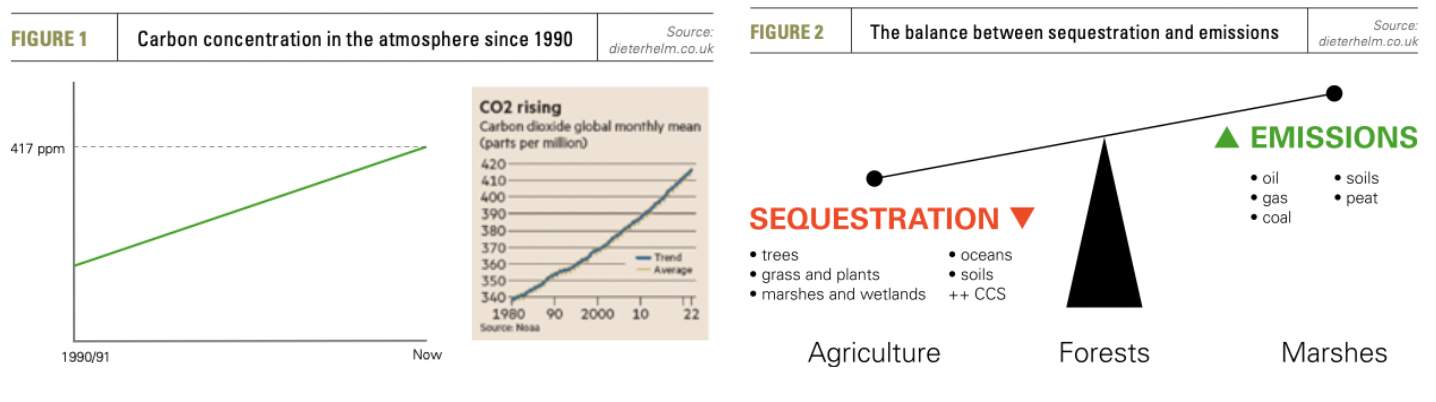

The net result of these mechanisms is that the carbon concentration in the atmosphere has been going up remorselessly by 2 ppm every year since 1990 (see figure 1) and it is still the same today. In other words, so far there is no transition. Reducing emissions has not made a difference because natural sequestration (see figure 2) is not working – it is actually deteriorating.

The world is concentrating on cutting emissions, but it is leaving out half the problem (see figure 2). Last year the Brazilian Amazon became a net emitter - one of the greatest carbon sinks of our planet no longer is one. And it is not just deforestation. Expanding agriculture is adding to this damage. It is destroying the ability of soils to absorb and hold carbon. What happens when agriculture in Africa, where productivity is very low, catches up as the population grows? Helms emphasised that “managing our natural world is as important as managing emissions.”

The world is spending time planning how to get emissions down, including how to get out of burning fossil fuels – of course quite important. But it is spending less time thinking about the damage expanding agriculture is doing to soils, wetlands and peats and the damage deforestation is doing. The world is still burning and clearing forests at an alarming rate, with no end in sight – at least not within this decade.

It is in places like Africa, India, Indonesia, Brazil and China where the transformation from a warming world to one where climate is stabilised will be won or lost. What Europe and the US are doing to address climate change is important, but this is a global problem. The key for the future is the economic transformation still to come if the living standards of people in the developing world are to catch up with the developed world. That is where population growth is and where economic growth is still to come.

The world has had 26 COPs so far but it is not yet on a sustainable transition path. A lot more needs to be done if global warming is not to reach and exceed 3ºC, let alone stay within the Paris Agreement goal of 1.5 to 2ºC. In effect COP26 was too little too late. “We need to address carbon consumption, not just production,” Helm said. What the world needs is a realistic and credible strategy that COP26 did not provide.

The enduring importance of fossil fuels

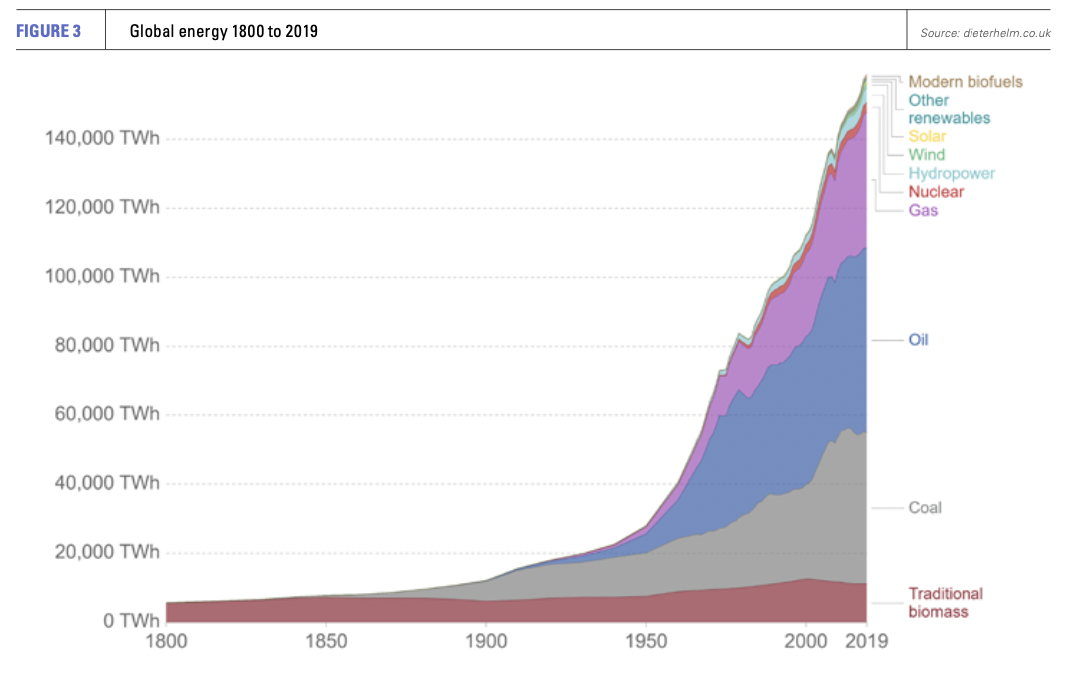

The reality is that since 1970 about 80% of global energy comes from fossil fuels (see figure 3). What has been achieved during the last ten years is to replace some coal by natural gas – but only some.

The world has not yet had any serious transition to renewables to make a difference. There is no evidence that much has been done to squeeze out oil, gas and coal. China is building many more coal-fired power stations than the US and EU are closing.

In the light of the current energy crisis and high prices – especially high gas prices – the irony is that the big winner, even in Europe, is coal. It should have been a boon for low carbon energy and renewables, but it is not. This is the reality the world is confronting. Energy transition has not really started yet, but it needs to if the world is to avoid a future catastrophe.

Current nationally determined contributions (NDCs) will lead to a 2.3ºC global warming if they are fully adhered to. But evidence shows they are not. Without change, this is likely to lead to 3ºC+.

The world needs to get out of coal. Coal to gas substitution is a key part of energy transition.

But India is experiencing a massive increase in coal production and consumption, providing 75% of its electricity. The driver behind this is cooling, to deal with searing heat, probably exacerbated by global warming. Reducing energy consumption in a world that is getting much hotter, where cooling is becoming a major concern, will be a challenge.

The crisis and the importance of gas

And while this is happening, along comes the oil and gas crisis that started well before the Ukraine war. The war exacerbated it.

With the world coming out of the pandemic, economic recovery set in motion a commodity price boom and oil and gas and energy prices increased sharply. That was the logical consequence of what happened during the pandemic and before. Quantitative easing (QE), printing money, running serious negative interest rates over a long time meant that too much money ended up chasing too few goods, driving prices and inflation up.

So what happened to all those world leaders that were so bent on getting out of fossil fuels? The outcome is a return back to fossil fuels. In the UK Boris Johnson now wants to keep North Sea oil and gas flowing to help tackle the UK’s energy crisis and the rising cost of living, and has urged companies to boost investment, despite his climate pledges, which now ring hollow. President Biden is off to Saudi Arabia, despite labelling it a “pariah state” not too long ago, to plead for more oil and lower oil prices. The push to address climate change is still there, but somewhat blunted by the crisis.

What the Ukraine war brought home is that fossil fuels are still existential to global energy systems and that global energy security and geopolitics matter.

The world needs to pursue development of renewables going forward. But low energy density, intermittent and disaggregated renewables need back-up. That means that with the increase in the adoption of renewables, gas is becoming even more important than it was before, including LNG. The sources of LNG are quite limited, with diversification of supplies becoming incredibly important. Falling back into coal is not a choice in a world that aims to arrest global warming.

As the world pushes for more renewables, the requirement for gas as back-up increases. But intermittency of renewables makes gas intermittent, making the operation of gas power facilities that much more expensive than otherwise would have been. As long as intermittency remains an issue, the world needs a transition strategy for gas, not just for renewables.

High prices should incentivise more investment in new gas and LNG resources. But for this to happen, the US and the EU must stop scapegoating gas and give clearer signals that gas will be needed well into the future. Not doing so will lead to another crisis in a few years down the line, as supply shortages become more acute.

The world cannot do the transition relying only on intermittent, low density, disaggregated renewables – they need back-up. Gas is a necessary part of the solution. But the gas industry must also get serious about addressing methane emissions and about adopting CCS at large scale.

The world needs to get serious about energy security and energy transition, but simultaneously, not just the net-zero part, including also natural carbon sequestration.

If this is not recognised and addressed, the world will carry on adding 2 ppm to the global carbon concentration in the atmosphere, all the way to 3ºC+.

What should happen next

As soon as there is crisis, people are reminded of the reliance on fossil fuels and that energy security and consumer affordability matter. If consumers cannot pay the high prices, it becomes a political imperative. Politicians scramble to bring energy prices down by cutting taxes. The world and governments will need to think about how people pay for energy. It is a basic living requirement that all people are entitled to and it has to be affordable.

The world will need secure and affordable supplies of oil and gas for a long time to come. The 80% reliance of global energy on fossil fuels and the need for 100mn b/d oil will not go away that quickly. Bringing fossil fuel dependence down to 20% in 28 years is a huge undertaking – requiring a massive and costly industrial, economic and societal upheaval - and will take time.

But the world needs to get out of coal – not just stop the increase, but get it out of the energy system as quickly as possible, and fast.

It also needs to reduce energy demand. If not, we are not serious about climate change. It requires changes in personal lifestyles, but that is something no one is prepared to talk about.

What is needed is a global deal and China and Russia will need to be part of it. It is not just Western democracies that need to deal with climate change, but also all future emitters.

Limiting global warming requires becoming serious about carbon consumption, not just production, and about the carbon price. The world will have to make pollutants pay. And the polluters are not just the oil and gas companies or the airlines or the steel companies. That is an illusion. The polluters are those who buy their products – us. These companies do not make carbon intensive products for the fun of it. They make them because consumers want to use them – fuels, plastics and all other products made from fossil fuels.

If the world carries on on this unsustainable path, then the growth of carbon concentration in the atmosphere will carry on growing at 2 ppm per year, with the inevitable consequences, until environmental unsustainability hits home. One thing is clear: “What is unsustainable will not be sustained.”

The trouble is that the consequences have not yet registered with people fully to do something about it. As a result, without major change, the world is more likely to get climate change rather than a change in the direction of net zero.

It is time to recognise we are not really making any progress towards net zero. The idea that it is all the fault of the companies, and that if they all adhere to ESG principles it will all be fine, is dangerous. There is a huge gap between what the public is being told and reality. Getting to net zero will be costly. There will be crises along the way. There is no escape.