Dutch-UK line ready for reverse [NGW Magazine]

Built and operated by Dutch transporter Gasunie initially in order to help meet UK security of supply, so far the Balgzand-Bacton Line has only been able to carry gas from the Netherlands to the UK. But at the end of 2017, its wholly-owned subsidiary BBL Co announced it would make gas transportation in both directions possible from the autumn of 2019.

There had been pressure to act earlier, but whether there was not enough demand to justify the cost, given the abundance of gas available under Dutch soil, or whether the Netherlands did not want any more UK North Sea gas in the country, lowering prices, nothing happened.

And now a dozen or so years since start-up, and after engineering work at either end, BBL is now from this month able to flow gas in both directions. There is no compression yet built at Bacton on the Norfolk coast, so reverse-flow capacity will depend on the strength of the demand from consumers on the continent. The operator says a little over a third of the forward flow will be available in reverse: a maximum of 7 GWh/h (about 5.5bn m³/yr), compared with 20.6 GWh/h in forward flow.

As with the bi-directional Interconnector UK pipeline which links Belgium and the UK, the direction of flow through BBL will depend largely on the prices at either end of the line each day, flowing towards the higher-priced market as long as the difference between the two is sufficient to cover the cost of transport.

BBL did not explain how it would manage the pressure drop to allow reverse flow, or where the gas would come from to pressure up the line and so allow forward flow to resume.

Stronger hub

This makes the Netherlands stronger as a gas hub, able to source pipeline gas from the UK as well as Norway, and hence able to transit more gas to neighbours as well. It is already the most liquid in Europe, as home to the Title Transfer Facility.

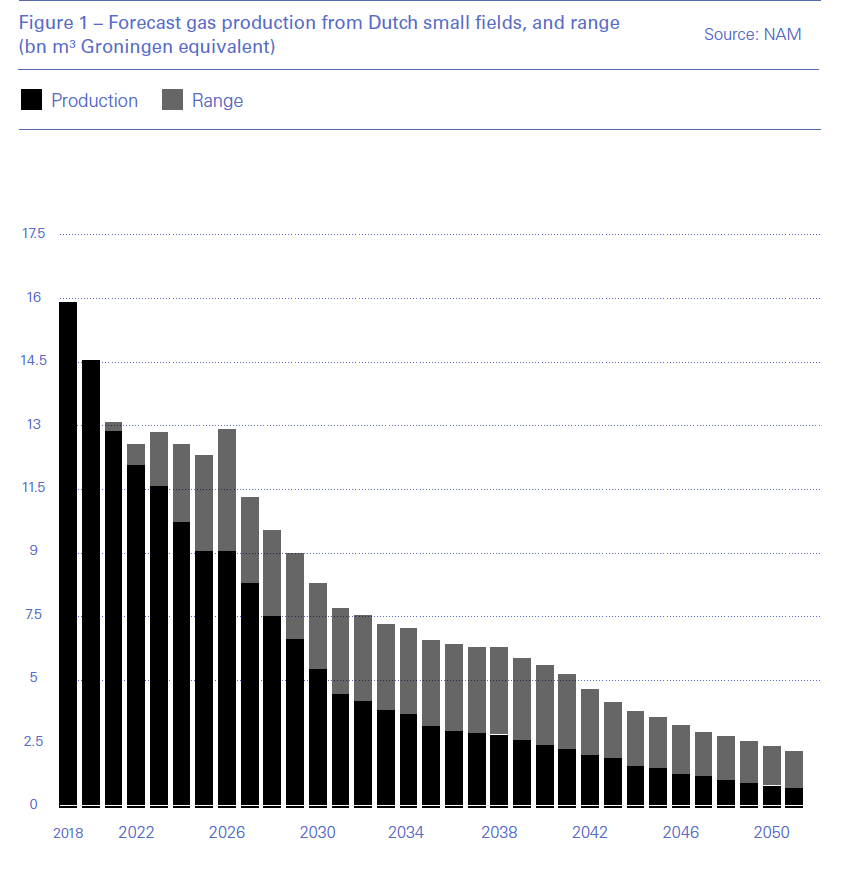

But the timing is nevertheless significant, as the Netherlands is losing a major source of gas, faster than expected, while output from the other fields collectively is declining (see graph).

The Dutch government is seeking to cut output from the nitrogen-heavy Groningen field altogether, although the state mining supervisor SODM has ruled that annual production of 12bn m³ would be safe. The decision to reverse flow was taken after the decision to cut Groningen.

One industry source told NGW that reversing the BBL flow was not directly connected to the output reduction of the Groningen field, but to declining domestic production in general. The reversal was planned and is part of the policy of the Dutch government, even before Groningen became an issue, to secure gas supplies in the future and to remain an international gas hub despite the depletion of domestic reserves, he said. “But you could say that the process has speeded up,” he concluded.

And the Dutch situation might worsen: the field’s operators – Anglo-Dutch Shell and US ExxonMobil, equal partners in the NAM joint venture – might not decide that it is worth operating it for such small amounts of gas after 2022, given the field is going to close completely anyway by 2030 at the latest. They could decide to meet their gas sales commitments from other sources including LNG; and wind up operations at their 60-year-old venture sooner.

The two majors are also part-owners of GasTerra, the exclusive marketer of Groningen gas as well as a buyer and seller of other gas, each with 25%. The government owns the other half of the company, but as a public-private partnership, GasTerra has to negotiate with its clients as its shareholders agree between themselves. GasTerra sells gas and it is the role of the wholly state-owned transporter Gasunie to ensure that the customer receives gas of the correct specification.

|

Dutch ministry must cut deeper: Council The Dutch economy minister must provide better reasons as to why gas extraction from the Groningen field cannot be phased out more quickly, said government advisory body the council of state July 3. Waving good-bye to the economic wealth represented by the remaining reserves – so far 2.1 trillion m³ have been produced – and buying more gas to honour the remaining contracts, was a painful decision, so cutting deeper will be cause even more damage to the economy. But the bad handling of the earthquake damage done to housing, initially denied as being the result of excessive production, led to a lot of anger in the Groningen area and left the government with no choice. Even now the earthquakes persist, despite the cuts in output, and the ministry has told NGW that it is always working on solutions to the output problem, even without earthquakes. In particular, the council said, the energy ministry had to explain better why it could not reduce faster the contracted low-calorie gas deliveries to three categories of user – importers, industrial buyers and greenhouse growers – which are all set up to run on Groningen gas. Dutch industry accounts for 15-20bn m³/yr. In setting the maximum volume of gas permitted for extraction in the gas year 2018-2019 (19.4bn m³, although with three months to go, as of end-June the field had produced just 13.9bn m³), the minister weighed the safety interests of Groningen's residents against security of supply issues. The council said he made a plausible case that extracting less could have significant repercussions on society. Furthermore, he had applied an acceptable standard to estimate the probability of the most serious safety risk, such as death as the result of an earthquake for this gas year, and that standard will also be met. The minister was therefore not required to lower the level of gas extraction for this gas year, it said. However, the minister's explanation does not meet the necessary standards of decision-making for the subsequent gas years (from October 1, 2019), the council ruled. The council of state told NGW that there would be more financial repercussions from cutting further and faster: and as the indirect 50% owner of GasTerra, the exclusive marketing agency for Groningen gas, the government will have to be involved in finding a solution. Which levers the minister decides to pull will be his decision, however. The ministry told NGW in June that it might be possible to cut more from next year's output than it planned but that it would only know the likelihood of that late this gas year. "The ruling is a signal that we must always do our very best to explain gas decisions. Of course we totally agree," it said. The goal is still to produce 15.9bn m³ from October 1, 2019 to September 30 2020, but it could be possible to reduce this by 3.1bn m³ to 12.8bn m³, he said. That is still a little higher than the 12bn m³ that SODM has ruled the safe upper limit. However there are two solutions that would bring demand down: the decision to accelerate the conversion of a power plant near Cologne to run on high calorie gas; and the operator of the Nord storage facility, used for Groningen gas, will build a facility where Groningen gas will be mixed with high-calorie gas. These two projects could possibly lead to an additional saving of 0.8bn m³ by 2020. It is a fast-moving target: the ceiling of 15.9bn m³ for next year was set in February this year, reducing the previous target by 1.5bn m³ owing to lower than expected exports to Germany and the additional purchase of nitrogen. |

|

Dutch government must act soon: VEMW In an interview with NGW, the CEO of Dutch industrial energy users’ body Hans Grunfeld said that time was running out for his members. Between them, nine of the largest could cut demand for Groningen gas by 3bn m³/yr but to do that means action now and their hands are tied. GTS can add nitrogen to the mix, especially for exports; and further cuts to 5bn m³, with an extra 7bn m³ of pseudo-Groningen gas, are possible from then on (gas year 2021-2022); but the question is how the nine biggest gas consumers, with demand totalling 3bn m³/yr, can be switched over to high-calorie gas. “They have submitted their proposals to the government and have not had a reply, leaving little time to agree compensation for the investments if they are to start on time for the October 2022 gas year. A year after being told by the government to cut their use of Groningen gas, they have done their homework and now the government must act,” he said. The government has drafted a law that will bring an end to Groningen gas and has asked advice from an independent commission of experts on an appropriate level of compensation, bearing in mind that all business face risks to their plans. But so far the government has not given its decision and so there is a limited window of opportunity. GTS will have to secure wayleave for building pipelines to the high-calorie gas grid, for example. “A bigger question though is, what is the rationale for further Groningen cuts? By 2022 the big nitrogen facility [able to create 7bn m³/r of ‘Groningen’ gas] will be online and there will be a further reduction of Groningen gas exports as the contracts expire. So there could be a substantial investment made in order to switch to high-calorie gas, just for a short period. “The point is that the state’s adviser, SODM, has said that 12bn m³ is a safe maximum; and while the government should strive for that limit as soon as possible, below 12bn m³/yr is a grey area. The current plans allow Groningen to go to 5bn m³/yr by the end of GY 2022. As export contracts expire and alternative arrangements materialise, that may be sufficient a cut [until the immovable date of 2030] rather than cutting the extra 3bn m/yr from these big users for what could be a very short period,” he said. The government initially wrote to 175 gas consumers whose individual demand ranges from 100,000 m³/yr to 500mn m³/yr, but it then realised it made no sense to make 200 new connections; and so it picked just the top nine biggest for that short period. VEMW responded, saying that GTS was best placed to come up with a sensible package, given its overview of the entire system. “The fairest way for society to cover the costs of conversion to high-calorie gas would be to spread them pro rata across all consumers, because the problems caused by Groningen gas production cannot be attributed to individual consumers,” he said. “2030 is the official end-date for Groningen, but if Groningen produces less than 2bn m³/yr I doubt if it will be economic at that low level. It is very clear that there is broad consensus that Groningen should be closed. But the speed, and how to treat its consumers, are key questions. There are many options and GTS has a well documented plan. We argue that if we want to do something that goes beyond that plan, regarding the nine major users, the government should respond to their proposals,” he concluded. VEMW understands the position GasTerra is in: the chairman of VEMW is Gertjan Lankhorst, who resigned as CEO of GasTerra to take up his VEMW role. |

|

Small fields on the way out: NAM Dutch producer Nam said July 12 that the small fields, mostly offshore, will not be able to produce more in the coming years and that to assume otherwise, as a means of offsetting declining Groningen output, was mistaken. “The total gas production from the small fields in the Netherlands is actually decreasing, this will not change,” it said. There had been reports of fields producing more than they were licensed to, which was not allowed. “This falling trend has already started at the beginning of this century and will therefore not change. In addition, no new fields are tapped through existing gas wells by Nam,” it added. Nam cannot produce more than the recoverable amount from the field, and the efficient production of existing and the occasional new small gas fields can “somewhat maintain production but do not increase it. On balance, gas extraction from small fields is decreasing slightly more every day.” Nam and other operators have had to adjust dozens of extraction plans in the last four years at the request of the ministry for the economy and climate, it said. “The adjustments are entirely independent of production from the Groningen gas field and would also have been implemented with the same production from Groningen.” |