EastMed: another Nabucco? [NGW Magazine]

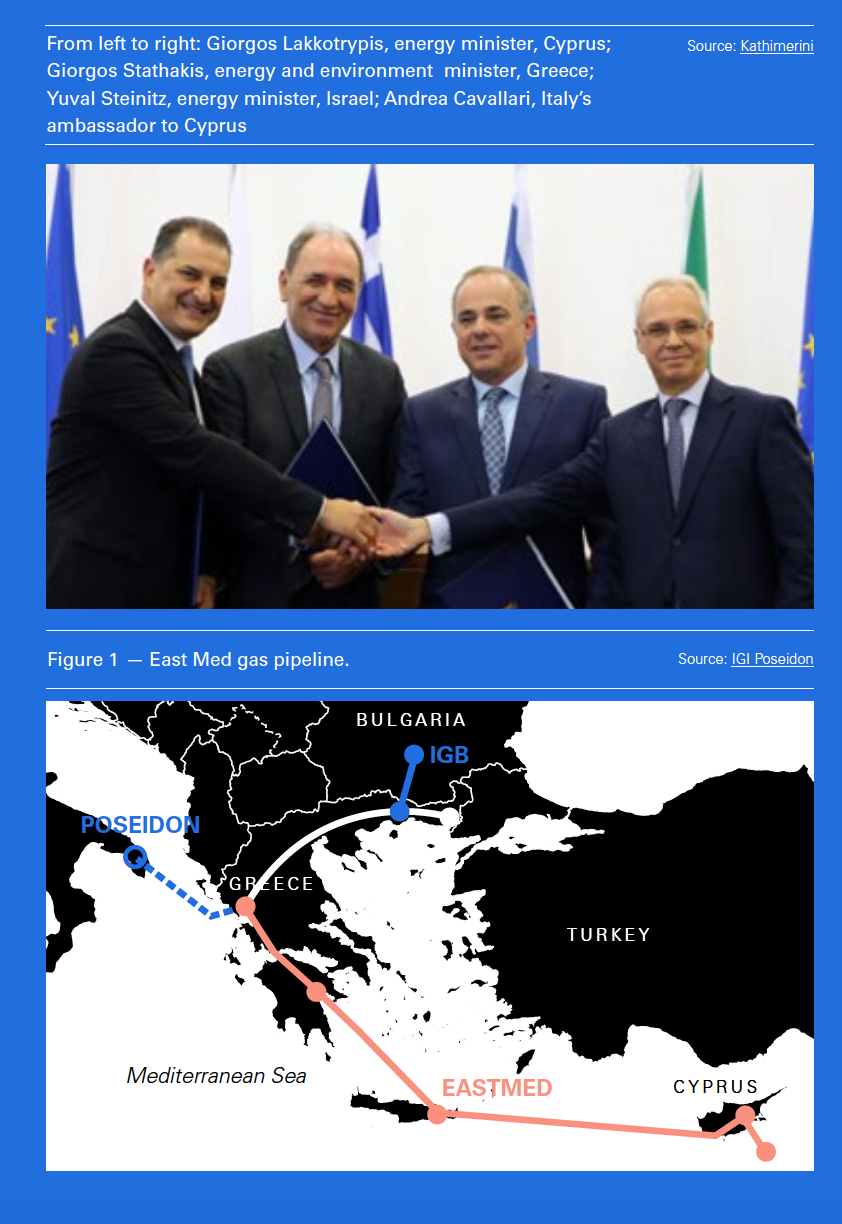

The EastMed gas pipeline from Israel through Cyprus and Greece to mainland Europe is back in the limelight. It was reported November 24 that, seven years after the concept was first proposed, the governments of Israel, Cyprus, Greece and Italy had reached agreement on the construction of this pipeline based on the results of a feasibility study funded by the EU.

However, government sources from Cyprus said that even though an inter-governmental agreement is in sight, a few weeks are still needed to complete the process and obtain approval by the European Commission (EC).

The project is being performed by Edison, an EDF Group company, and Greek gas supply company Depa with about €35mn ($40mn) funding from the EC, as a project of common interest (PCI). In a recent presentation Depa reported the capacity of the pipeline to be between 10bn and 16bn m³/yr. The project is designed to initially carry 10bn m³/yr some 1,900 km from the eastern Mediterranean to Greece, where it will connect to the Poseidon pipeline to Italy, about another 300 km (Figure 1). With 1,200 km offshore, if built this would be the world’s longest subsea pipeline project.

Although it would be a big deal for this region to export 10bn m³/yr, it is only about a fiftieth of European demand. This should put into context exaggerated claims from the region that EastMed will “to some extent minimise Arab influence on Europe.”

The fate of the Poseidon pipeline lies on whether TurkStream 2 choses to connect to this, to TAP or go through Bulgaria to Europe. The likely route appears to be the latter, but no final investment decisions (FID) have yet been made. But IGI Poseidon’s website states rather optimistically that FID is expected by mid-2019, even though to date no gas buyers or investors have been secured.

Without the Poseidon pipeline in place and operational, EastMed cannot deliver gas to Europe, unless of course only the part of the Poseidon pipeline connecting EastMed to Italy is built and the cost is added to the project.

These uncertainties are symptomatic of the whole project. The EastMed gas pipeline so far has the support of the four governments and the EC, but no international oil company (IOC) or investor has yet expressed interest in joining.

Indeed the IGI Poseidon website states that the “project development activities are now focusing on performing marine surveys along the route, in order to improve routing accuracy and to finalise preparation of the tender packages for initiating the proper development phase, that would allow the project to reach investment decision status.”

But there is no mention of how this will be achieved. The four governments and the EU cannot fund the project. This requires IOC and investor participation, and above all it requires buyers for its gas.

The project

IGI Poseidon states that the pre-front-end engineering and design (Feed) studies have confirmed the project to be technically viable, economically feasible and commercially competitive, but no details are given.

The most challenging part of the project is its section from Cyprus to Crete, which reaches a depth of over 3000 metres. Laying the pipe at such depths is challenging – stretching the limits – but technically feasible. However, the terrain is very uneven and the area is seismically active, subject to landslides. This could pose integrity and repair challenges.

IGI Poseidon defines ‘economically viable’ on its website as meaning that the current estimate of capital expenditures is lower than similar-capacity import projects to EU and sustainable within a range of EU gas prices scenarios.

The total cost of the pipeline has been estimated to be about $7bn, but most experts consider this to be optimistic, expecting it to be closer to $10 bn.

With initial gas quantities expected to be 10bn m³/yr from the Levantine Basin, almost all of the gas will be from Israel. Phase 2 of Leviathan is estimated to add another 9bn m³/yr to production, with all gas destined for export. Currently there is no indication on timing, but from the technical point of view Phase 2 could conceivably be operational by 2025. This is also the year IGI Poseidon expects the pipeline to be available to transport gas.

If all of the Leviathan Phase 2 gas is exported through the EastMed gas pipeline there will be no room left for Cypriot gas, for example from the Aphrodite gasfield. In any case, if one is to rely on recent statements from Cyprus, Aphrodite is on the verge of signing an agreement with Shell to export its gas through the Idku LNG plant in Egypt.

Leviathan gas is expected to cost between $4 and $5/mn Btu, even before it enters the pipeline. Allowing for the cost of the pipeline, by the time such gas reaches Italian consumers it will be too expensive.

Europe is well-supplied with gas from Russia, Norway, North Africa, Qatar, the US and others. Europe’s gas demand is not expected to increase significantly in future, with the decline in indigenous gas production well-covered by Russian gas and LNG imports, with other forms of energy making inroads into the gas market. The EC and Gazprom agreed in May “binding obligations on Gazprom to enable free flow of gas at competitive prices.” In addition, US LNG is well poised to increase its penetration of Europe’s gas markets.

Most forecasts at conferences in Europe expect spot gas prices to come down and by the mid-2020s – when the pipeline is scheduled to be operational – to be about $6/mn Btu, which is at least half as much again as Gazprom’s break-even delivered price. In addition, US LNG companies are confident they will increase their sales to Europe at about $6.50/mn Btu.

These are the prices that EastMed pipeline gas may have to compete with if it is to secure export markets in Europe – a big challenge.

Geopolitical challenges

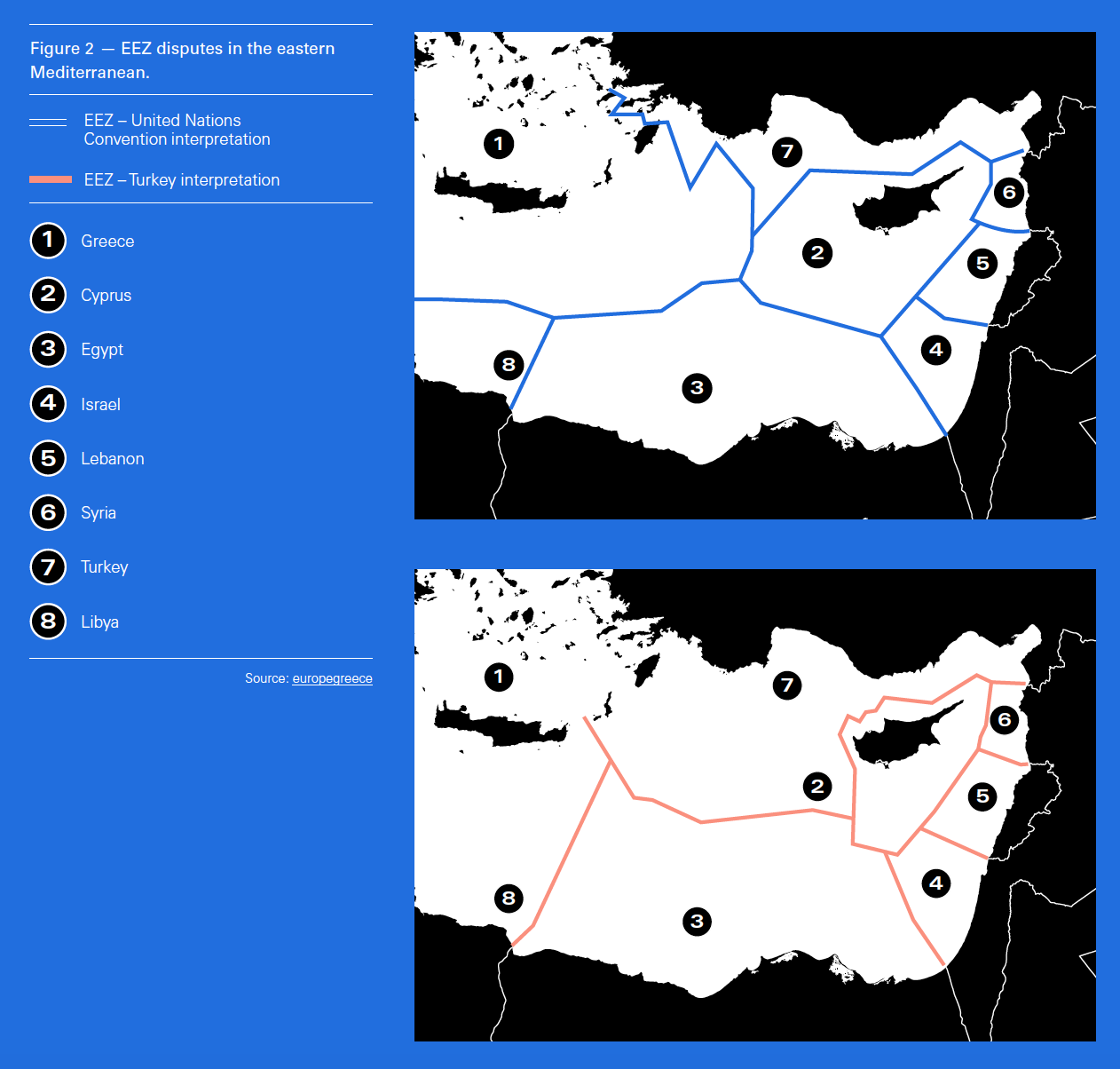

The area between Cyprus, Egypt, Libya, Greece and Turkey is characterized by disputed exclusive economic zones (EEZ) and unresolved conflicts. Applying the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Seas results in the first map in Figure 2, with a common EEZ boundary between Cyprus and Greece, exactly where the EastMed gas pipeline is planned to go. This map is acceptable to Cyprus, Greece and Egypt.

However, Turkey has its own unique way of defining what constitutes an EEZ. In this, in effect, islands are entitled to territorial waters but effectively no EEZs – the continental shelves of mainland states take precedence. This interpretation results in the second map in Figure 2.

None of the EEZs in this disputed region of the eastern Mediterranean has been formally defined, even though at one of their tri-partite meetings the heads-of-state of Cyprus, Greece and Egypt agreed to initiate a process to do just that. Turkey’s immediate response was to issue warnings against this, with threats that it will defend its national interests. However, no action has been taken so far by any of the parties.

According to the second map in Figure 2, the EastMed gas pipeline would pass through Turkey’s EEZ. Even if that were so, under the Energy Charter, to which Cyprus, Greece and Turkey are signatories, Turkey would not be able to stop it. But it could make it difficult by objecting on routing, environmental and economic grounds.

However, it is important to stress that at this stage there are no formally defined EEZs in this region, leaving unclear the rights, or otherwise, of the respective countries.

A ‘deja vu’?

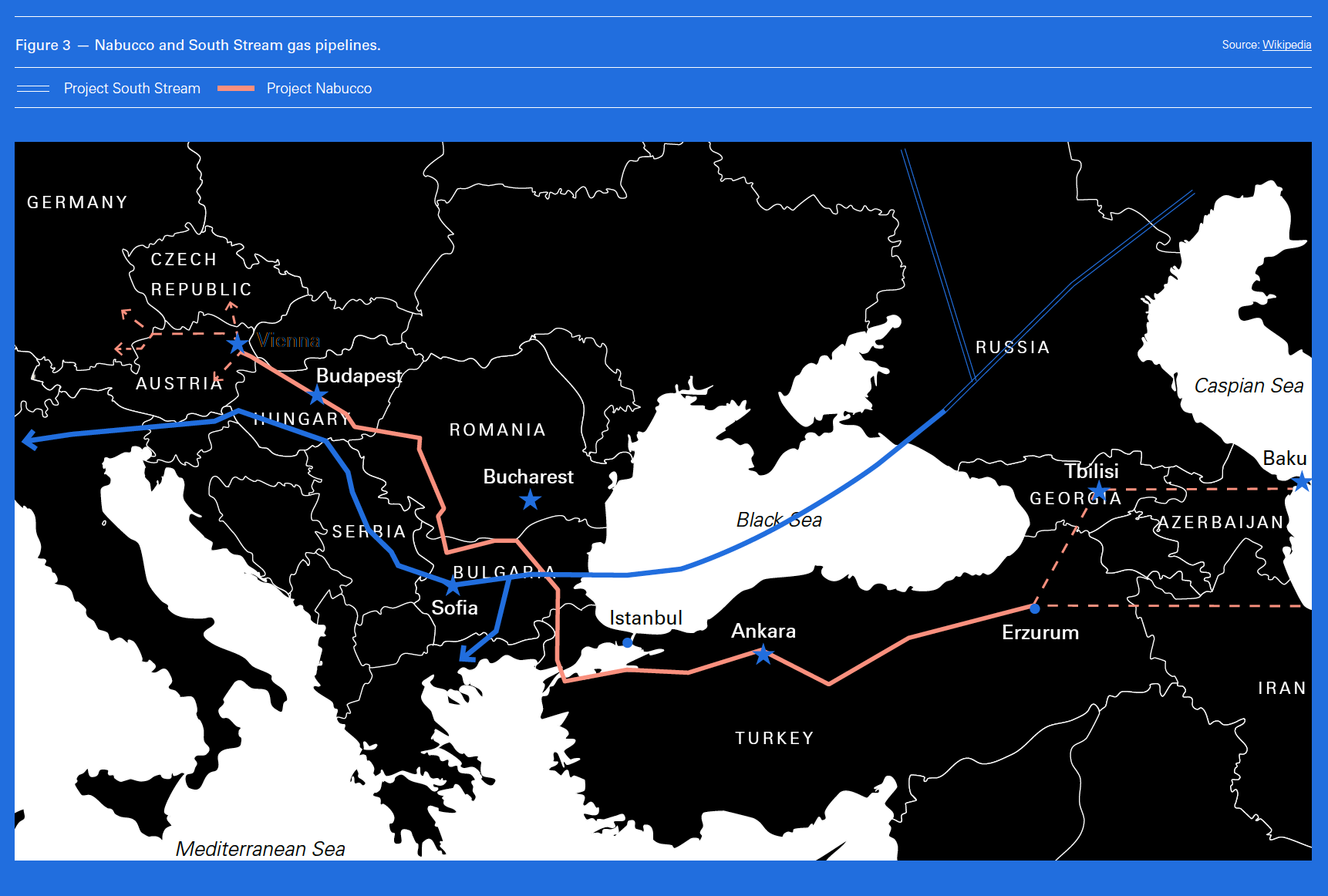

In some respects this project has pronounced similarities with the ill-fated Nabucco gas pipeline project, abandoned in 2013. Conceived by politicians, with all good intentions in the early 2000s, it proved to be a pipeline fraught with challenges, unable to attract commercial interest.

Nevertheless it was a regular feature at European gas conferences for a decade or more, its purpose being to fill up the gap left by indigenous production, in the days before US LNG exports became a serious proposition, to force competition on Russia and create a more reliable transit corridor than Ukraine. Numerous intergovernmental agreements were signed covering the transportation terms through the transit countries, but the exact source of the gas was never identified.

However as candidates included one or more of Iran and Iraq, the Caspian generally and possibly even Turkmenistan – an unquestionably gas rich region if politically fraught – the supply side of the equation was feasible.

At the time, both Russia and the EU declared that Nabucco and the then proposed South Stream pipeline – now replaced by TurkStream – were not competitors (Figure 3). But they were both designed to provide gas to the same southeastern European markets, where gas demand was then comparatively limited and competition equally so. Conventional wisdom was that Nabucco failed for political reasons, but the real cause of its failure was the emergence of more economically viable pipeline proposals.

EastMed was also conceived by politicians and is slated as a pipeline needed to provide Europe with much-needed diversification of supply.

But Europe’s perceived need to diversify away from, and cut dependence on, Russian gas has, to a great extent, been negated by the May agreement between the EC and Gazprom. This imposed binding obligations on Gazprom, with the outcome of opening up European gas markets to cheap Russian gas, taking the edge out of the need for diversification. Governments do not buy gas but companies do, for profit, and the biggest of these are already partnering Gazprom in its projects, such as Nord Stream 2.

As a result, TurkStream 2 has now become reality, destined to supply gas to the same markets as EastMed but at more competitive prices – a deja vu with Nabucco and what led to its demise.

Competition

And TurkStream 2 is not the only competition. The TransAdriatic Pipeline is well advanced and it is scheduled to deliver 8bn m³/yr gas to Italy and possibly to Bulgaria by 2020. In addition, Eni is planning to increase the Zohr gas production plateau from 28bn m³/yr to 33bn m³/yr by 2019, with the additional 5bn m³/yr destined for liquefaction at the Damietta LNG plant in Egypt and export to Italy. All these projects will be delivering gas to southeast Europe much earlier that the EastMed gas pipeline. By the time the EastMed is built, the markets in southeast Europe are likely to be saturated with gas – in effect making EastMed unnecessary.

So what is driving these governments, and particularly Israel which has been the most vociferous supporter, to pursue this project? A key factor is the challenge to secure export markets for the region’s gas, and perhaps through this gain wider international influence.

If nothing else, the EastMed has brought Israel, Cyprus and Greece into a closer alliance, bolstering co-operation in a region fraught with conflicts. But at this stage the EastMed remains just a political agreement of intent, still far from reality.

So far it has been easier finding gas in the region than exporting it. Israel has just announced a second offshore licensing round. Attracting IOC interest is highly dependent on its ability to export.

Like many other EU-funded PCIs, EastMed and Poseidon are facing challenges. So far only 8% of all gas PCIs have progressed to construction stage. In addition, the EU is now shifting interest from gas to supporting electricity projects.

Moreover, with the relentless penetration of renewables, global energy markets are becoming increasingly challenging. Europe has just upped its 2030 targets for renewables and energy efficiency to 32% and 32.5% respectively. These mean a cut in fossil fuel demand. Competition to secure markets will become increasingly fierce, with only the most competitive projects succeeding to secure markets.