Editorial: Fool's Gold [NGW Magazine]

The London Stock Exchange’s decision to lump oil and gas producers together with coal from July 1 as ‘non-renewable energy’ stocks is a perfectly logical one, on a somewhat pedantic level.

It has also captured the zeitgeist perfectly, as much of the world of energy appears to be caught up in a galloping inflation of decarbonisation ambitions. Ill-thought out and seldom costed, these plans are difficult to challenge without incurring wrath. Like accurate weather forecasters predicting rain, these Cassandras who put $1 trillion price tags on net zero carbon targets in just a few decades are betrayers of the revolution. And there is no shortage either of researchers who can confidently put reports together to illustrate this negative point or that about fossil fuels, knowing that they will be picked up and uncritically summarised by the mainstream media.

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

And yet this blurring of the three kinds of producers does a – no doubt unintentional – disservice to the former pairing, since coal has no good qualities that are lacking from oil and gas, while at the same time it carries the much heavier burden of carbon dioxide and lethal particulate emissions when combusted. The three however are now pigeonholed together, standing in enforced opposition to ‘renewable’, formerly ‘alternative’, energy companies – with all the positive connotations that new designation brings. They are now mainstream enterprises with their own corporate culture, not the 1970s-era hippies of yore.

Even ‘gas and oil’ had drawbacks as a definition: it is too crude, pardon the pun, for the wide range of companies that it embraces. Russian independent Novatek, for example, has retained its place on the FTSE4Good index again, allowing the company to talk about exporting clean energy to displace dirty fuels in overseas markets, and its good environmental, social and governance aims. No idealistic sentimentalists, the company is achieving all this while operating at above nameplate capacity and maximising shareholder returns.

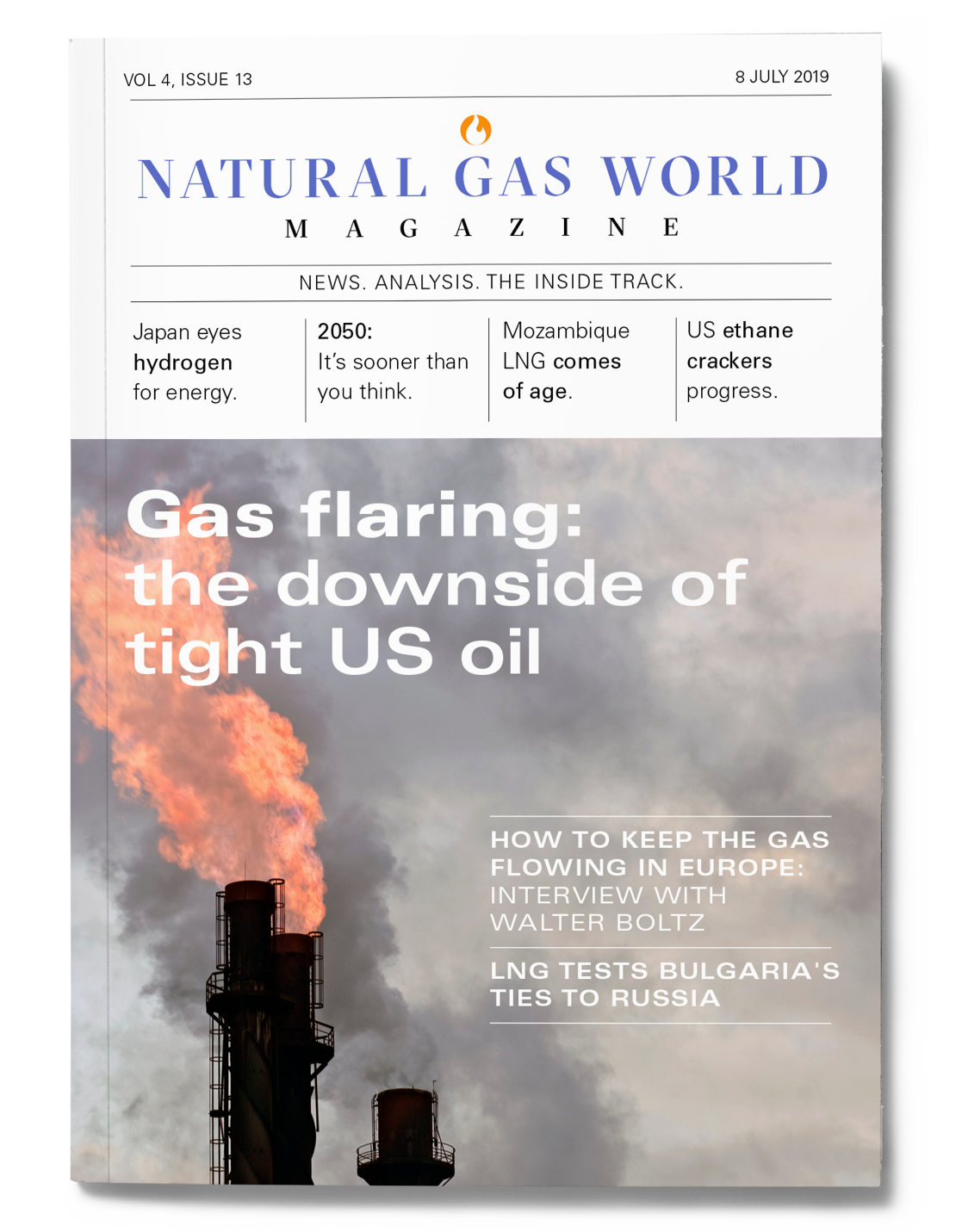

Other Russian oil companies and US ones too, for that matter, by contrast are major violators of environmental norms. Miles from any spare pipeline capacity, they are flaring associated gas as if it were going out of fashion in their quest for low-cost oil, as the feature on flaring shows.

Category titles are also a blunt instrument, when determining what part of a company’s business is gas. While gas production and oil production are easy to convert into barrels of oil equivalent to find which commodity predominates, the picture becomes cloudy. By the time the whole refining, diesel retailing and petrochemicals sectors are taken into account, for many of the majors the balance tilts back, from rough equivalence at the wellhead, to oil at the bottom line.

The fact remains though that coal stands in fierce opposition to gas, which seeks to replace it; whereas it will be some time before renewables are able to replace gas in a practical, affordable manner. They do not therefore belong in the same grouping. Indeed, often heavily subsidised renewables already owe much of their success and growth to gas, since no other fuel has accommodated them so readily, thanks to its flexibility in power generation, ramping up and down at very short notice and receiving the negative price on hot Sundays.

The corporate cemeteries packed with northern European gas utilities and the billions wiped off the share value of the survivors in recent years is testimony to the pain they have gone through. What is happening now is the morphing of oil and gas companies into energy companies with investments into all kinds of sustainable growth, meaning primarily power solutions but also new forms of transport fuel and eventually carbon-free gas – hydrogen, with or without carbon capture, use and storage.

The majors have the money, the balance sheet strength to survive. And they have the activist shareholders holding them to account, fearful that their shares will become junk if the boards do not implement swift change to keep the pension funds happy. The pace of divestment out of these stocks is fast, although perhaps partly disguised by companies’ own aggressive share buy-back programmes, which are a way of retaining value during the adjustment to a low oil price.

The failure of gas to replace coal hangs on commercial and political, not practical considerations. Gas can now be taken to every part of the world where it is needed, thanks to LNG technology. Energy independence and price can be primary considerations for governments that need to fuel predictable economic growth without interference from neighbours. Nevertheless, there are exceptions to that: Israel, for example, where investment fund Kerogen and Energean are working together on gas production that will displace coal from Israel’s energy generation mix. France is also getting out of coal early: its decision to close down its coal plants, long before their active life was over, persuaded Uniper of the need to sell all of its French assets, gas and solar included.

Energean is now wealthy enough to buy France’s other energy giant’s upstream assets, those of EDF, for at least $750mn. Engie sold its own a few years ago, as it underwent its own conversion to the energy transition. Energean has become a player in northwest Europe, a region that is already home to much merger and acquisition activity as new companies, backed by new money, see new value. And Neptune Energy, which bought Engie’s upstream assets, is even working on an offshore hydrogen plant to generate power for a Dutch platform.

As always, with broad-brush terms, the devil is in the detail, and the seller of the stocks, as well as their buyer, must beware. He might be keeping the chaff and losing the wheat.

NGW Magazine Volume 4, Issue 13 is now available to Premium Subscribers.