Egypt juggles gas export options against domestic needs [Gas in Transition]

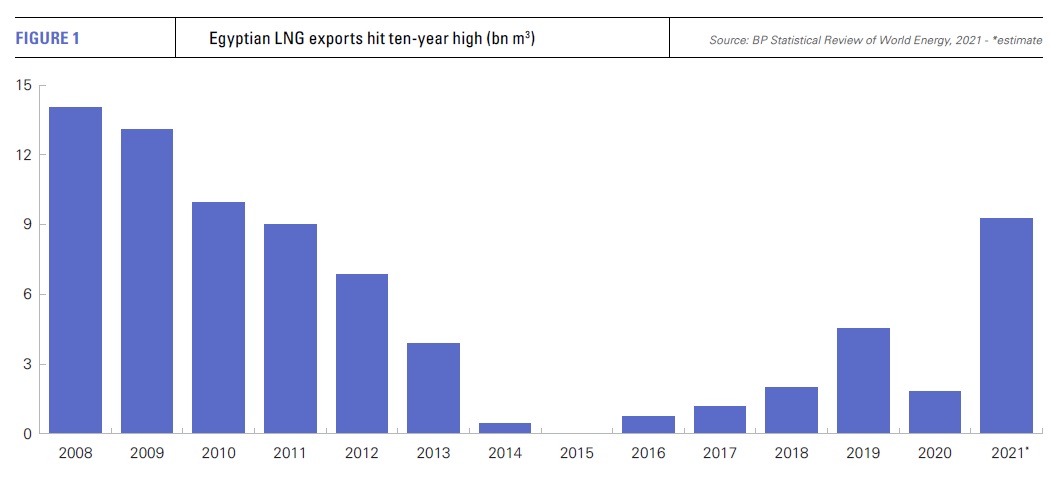

New discoveries and high international gas prices saw Egyptian LNG production jump last year as mothballed capacity was brought back on stream. Moreover, growing export capacity, both as LNG and by pipeline, alongside higher domestic pricing, has boosted interest in Egyptian upstream exploration.

However, the government faces a difficult challenge in finding the right balance between growing domestic consumption and higher exports as it begins to realise its dreams of emerging as a major regional gas hub. Increased domestic exploration and gas imports from Israel and/or Cyprus are all promising options.

The current situation is a huge turnaround from just a few years ago. Domestic gas production fell by about 30% between 2009 and 2015 to 4.3bn ft3/day, with domestic gas shortages occurring from 2013. LNG exports from the country’s two LNG plants, Damietta and Idku, were dramatically curtailed and Damietta was closed for eight years.Rapid turnaround

Egypt even turned to LNG imports via floating storage and regasification units between 2014 and 2019, but the Egyptian General Petroleum Corporation (EGPC) was able to cancel the FSRU contracts when it became clear that new discoveries would make further imports unnecessary.

The new finds were headlined by the giant Zohr field, which was discovered by Italian major Eni in 2015, about 155 km offshore on the Shorouk block. With estimated reserves of 30 trillion ft3, Zohr is the biggest gas field in the Eastern Mediterranean. Its rapid development changed everything.

The field now yields 2.7bn ft3/d, while more new production has come from Eni’s Nooros field and BP’s North Alexandria West Nile Delta and Nooros projects. According to BP statistics for 2021, Egypt’s proven gas reserves now stand at 75.5 trillion ft3, the highest ever level, giving it the 16th biggest national reserves worldwide.

Gas production in 2021 was a record 7bn ft3/d, even if this figure is below the 7.5bn ft3/d forecast by the petroleum ministry (see figure 1). As a result, Egypt was able to export 6.8mn mt of LNG in 2021 (see figure 1), about ten times more than in 2020.

More gas needed

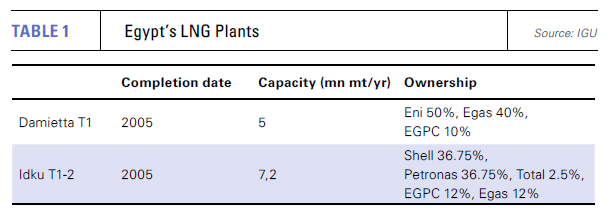

In December, petroleum minister Tarek El Molla announced that both of the country’s LNG plants were operating at full capacity for the first time in more than ten years. The Damietta plant, which is operated by Eni, has nameplate capacity of 5mn mt/yr, while the Shell-operated Egyptian LNG (ELNG) facility, also known as Idku LNG, can produce 7.2m mt/yr (table 1).

However, higher domestic gas production or imports are still needed. El Molla says that increased domestic summer demand means that LNG production will probably be curtailed for a period this year, with supplies to the two plants likely to fall to 1bn ft3/d from the 1.6bn ft3/d they currently receive.

Both Zohr and BP’s Raven gas condensate field suffered upstream outages last year, which threatened gas supply to the country’s LNG plants. Exports were not consistent throughout the year, dipping sharply in the summer, but recovering in the fourth quarter. As a result, and given El Molla’s comments, it may prove difficult to sustain LNG exports this year at the same level as 2021.

Subsidies persist

The Egyptian government has gone some way toward reining in domestic gas consumption by reducing both gas and power subsidies. Its fuel subsidy bill increased last year because of rising butane costs, but Cairo insists that it is on course to entirely phase out the subsidy programme in the longer term. In October, it increased the price of natural gas sold to industrial consumers from $4.5/mn Btu to $5.75/mn Btu for high volume consumers and to $4.75/mn Btu for the rest of the industrial market.

However, while raising domestic gas prices should act to dampen demand, there are other big drivers promoting increased consumption. Cairo has set a target of raising the number of residential gas customers from 4mn in 2017 to 10mn by 2025, while the completion of the world’s three biggest combined cycle gas-fired plants – Beni Suef, New Capital and Burullus – by Germany’s Siemens has placed more strain on domestic supplies to feed their combined 14.4 GW generating capacity.

Strong economic growth should also boost domestic gas demand. While most other economies struggled, GDP growth only fell to 3.3% in fiscal year 2020-21, at the height of the Covid pandemic, partly owing to $11.3bn in IMF support for government finances during the crisis.

Annualised growth of 7.7% in the final quarter of 2020-21 and positive investor sentiment about the country’s economic prospects both point towards continued energy demand growth for the foreseeable future. The government has set a target of 5.7% GDP growth for fiscal 2022-23.

Changes in power sector policy could ease domestic gas demand growth. Power plants currently absorb 65% of domestic gas supply (see figure 3), and the government now plans to encourage more renewable energy generation rather than new thermal power plants. Several big solar projects are already under development.

However, Cairo has pledged to cut national greenhouse gas emissions by replacing oil consumption with natural gas wherever possible in the rest of the economy. For instance, the ministry of the environment has announced that there will be a ban on diesel or petrol-powered buses from 2027, which will require the country’s entire fleet to be replaced by gas-powered and electric vehicles. There is no guarantee that the pledge will actually be enforced, but the announcement does at least indicate the direction of travel..png)

Regional gas hub

The government has made much of its plans to position itself a regional gas hub, making use of production in neighbouring states to maximise its liquefied and piped gas exports. Cyprus and Israel have both offered to pipe gas to Egypt for both domestic use and LNG production, although the latter is a politically difficult option for Cairo, with many Egyptians opposing any new trade with Israel.

Meanwhile, the Cypriot government has given way on its previous determination to see an LNG plant built at Vasilikos on the island in favour of cooperation with Cairo. Egypt and Cairo have already agreed on the construction of a new pipeline to transport gas from the former’s Aphrodite field to Idku.

Israel began exporting gas from its Leviathan and Tamar fields to Egypt in 2020 through the 90-km East Mediterranean gas pipeline, which connects Ashkelon in Israel to El Arish in Egypt, under a 15-year contract. The pipeline was originally built to transport gas in the opposite direction, but political tensions and repeated bomb attacks by Islamist militants on the Egyptian portion of the line saw Cairo halt the trade in 2012. Deliveries currently stand at 450mn ft3/d and are expected to rise to 600-650mm ft3/d by the end of the first quarter this year, meeting the pipeline’s full capacity.

However, the two countries signed a memorandum of understanding in December 2021 to further increase Israeli imports and El Molla has said that one option is for a new onshore pipeline to be built by 2025 at a cost of $200mn. It would be owned by Israel Natural Gas Lines, presumably in order to reduce the risk to Egypt.

However, the two countries signed a memorandum of understanding in December 2021 to further increase Israeli imports and El Molla has said that one option is for a new onshore pipeline to be built by 2025 at a cost of $200mn. It would be owned by Israel Natural Gas Lines, presumably in order to reduce the risk to Egypt.

The project would face significant security challenges given the threat to any line running through the Sinai Peninsula, where Islamist militants remain active and steadfastly opposed to any cooperation between Egypt and Israel. Plans for a second subsea pipeline have also been discussed, but this appears to be a separate proposal.

Production capacity on the Chevron-operated Leviathan field in Israel is in the process of being ramped up, while Energean is due to start production on the Karish-Tanin field this year, so there seems to be little doubt over Israel’s ability to supply any new pipeline.

Piped gas imports do look necessary as increased Egyptian piped gas exports would constrain the amount of gas available to supply Damietta and Idku. Egypt already supplies Syrian and Jordanian power plants via the Arab Gas Pipeline and the long expected extension to the line into Lebanon has now been completed. An outline deal to supply 65mn ft3/day to a 450-MW Lebanese power plant has been agreed and is supposed to start early in 2022. Given that the infrastructure has been put in place, this is likely to be achieved. However, no binding deal has yet been signed, despite several rounds of talks between the two governments

New LNG capacity unlikely for the moment

Further upstream finds would enable Egypt to juggle all of its gas commitments. Indeed, more attractive upstream terms of investment and excitement over recent discoveries have already boosted interest in Egyptian acreage.

Eni, which is the country’s biggest oil and gas producer, secured five new exploration licences when the results of the 2021 upstream licensing round were announced in January. The successful bidders for all eight blocks on offer are scheduled to drill at least 33 wells, while the government is expected to finance the drilling of 23 new wells by state-owned companies. Another licensing round is due to be launched in June, as Cairo seeks to keep the ball rolling on its gas sector success.

However, if tough choices have to be made, the assumption is that Cairo will continue to favour domestic gas requirements over exports. The Idku plant was originally planned with six trains in mind, but this now seems highly unlikely. Egypt is a long way from being able to sustain any new liquefaction capacity at present, but new trains could be considered, if further giant finds are made in the country itself or even in its supplier states.

Egyptian electricity alternatives

Egyptian electricity alternatives

Cairo aims to boost the share of renewables in its generation mix to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and limit demand for natural gas. The country has a renewable energy target of 20% by 2022, which is likely to be missed, 55% by 2035 and 61% by 2040.

According to the International Renewable Energy Association, Egypt had total renewable energy capacity of 5.98 GW at the end of 2020, of which 2,832 MW was hydro, 1,375 MW onshore wind, 1,673 MW solar PV and 21 MW concentrated solar power.

In 2021, an estimated 500 MW of new wind and solar came online, but a project pipeline of 2.4 GW suggests this should accelerate in coming years. The country’s first offshore wind farm, 500 MW in the Gulf of Suez area, is slated for completion in 2024.

The government also has long-standing plans for the construction of its first nuclear reactors and continues to reiterate its support for the technology. Plans are for 4.8 GW of capacity, possible coming into service in the late 2020s, to be built by Russia.

A number of electricity interconnector projects, including the proposed EuroAfrica interconnector, indicate that Egypt’s regional energy hub ambitions are not solely gas based. The government hopes that the country could also become a regional electricity exporter, with generation from renewables, nuclear and the gas-fired power plant.