Energy security: it’s all about gas interconnectivity [Gas In Transition]

The REPowerEU plan, published by the European Commission in May, targets investment of €10bn ($10.6bn) in new gas infrastructure deemed essential to delivering on the plan’s goals of ending the EU’s dependence on Russian gas before the end of the decade. Like never before, the crisis over Russian gas imports has refocused EU attention on the interconnectivity of the European gas system and, most acutely, critical gaps and bottlenecks that inhibit the use of existing import infrastructure.

Yet significant progress has already been made, largely the result of investments made in the wake of the Russia-Ukraine gas crises of the 2000s and 2010s. These investments now look invaluable as the EU reassesses its previously growing antipathy to investment in gas infrastructure.

Baltic LNG

Principal among the investments were the EU-supported LNG receiving terminals completed in Lithuania in 2014 and Poland in 2016. In addition to the new Baltic Pipe between Poland and Denmark, which will be complete this year, these gas entry points can now form the basis for north-south gas flows into central and eastern Europe, historically the part of Europe most dependent on Russian gas.

Interconnectivity will be hugely improved with the completion of the GIPL pipeline connecting Lithuania and Poland and the Poland-Slovakia interconnector this year. Along with already operational connections between Estonia and Finland, the Baltic region’s security of energy supply has been immeasurably increased by investment in LNG import capacity, while the construction of onshore pipelines means the regasified LNG can reach more and more markets inland.

This infrastructure will gain greater significance with the imminent completion of the expansion of Poland’s Swinoujscie LNG terminal, construction of a new LNG terminal in Gdansk, expected by 2025/26, and the temporary installation of a floating storage and regasification unit (FSRU) later this year in either Finland or Estonia. The Gdansk terminal will free up capacity at Klaipeda LNG in Lithuania and add capacity to allow regasified LNG to flow south to Slovakia and Ukraine. The European Commission has identified the accelerated construction of the North-South Gas Corridor in eastern Poland as necessary to allow gas entering at Gdansk to reach further south.

This infrastructure will gain greater significance with the imminent completion of the expansion of Poland’s Swinoujscie LNG terminal, construction of a new LNG terminal in Gdansk, expected by 2025/26, and the temporary installation of a floating storage and regasification unit (FSRU) later this year in either Finland or Estonia. The Gdansk terminal will free up capacity at Klaipeda LNG in Lithuania and add capacity to allow regasified LNG to flow south to Slovakia and Ukraine. The European Commission has identified the accelerated construction of the North-South Gas Corridor in eastern Poland as necessary to allow gas entering at Gdansk to reach further south.

These investments cannot come too soon. Russia halted gas exports to Finland in May, following the latter’s refusal to pay for the gas in rubles. Although Finland is not heavily dependent on gas, almost all the gas it does use is sourced from Russia, which has also cut off electricity supplies to the country. The ability to import gas from Estonia, which is in turn connected to the Lithuania system and Klaipeda LNG, means Finland should be able to survive the loss of Russian gas until the new FSRU arrives. Finland, along with Sweden, has also applied to join NATO, a move fiercely opposed by Moscow.

Southern entry points for eastern Europe

LNG is a critical element in the mix further south, where again the EU is by no means starting from scratch, owing to the completion of the Krk LNG import terminal last year and the first phase of the BRUA pipeline corridor in 2020. The latter is planned in three phases, with the eventual aim of creating an interconnector linking Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary and Austria.

This infrastructure is to be supplemented by additional improvements to the Bulgarian gas transmission system, including construction of interconnectors between Greece and Bulgaria and Serbia and Bulgaria. These are expected to be fed in part by LNG imported into Greece, where import capacity will be significantly expanded by the 5.5bn m3 FSRU planned for Alexandroupolis. This is expected to be operational from the second half of 2023.

Greece already has an LNG regasification terminal at Revithoussa, but its capacity of 4.6mn mt/yr saw only 36% utilisation last year as Greece imported more pipeline gas, in part through the new entry point of Nea Mesimvria, which is connected to the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline. As a result, LNG capacity at Alexandroupolis could be entirely used for onward gas transmission into neighbouring markets as new regional interconnectors are completed.

Expansion of Krk LNG has also been identified as a means of increasing regional gas supply, but this would be contingent on strengthening the Croatian transmission grid in the direction of Slovenia and Hungary, according to the European Commission.

France – the missing link?

Iberia’s lack of gas connection with the rest of continental Europe is long-standing and Spain has tried in recent years to drum up interest in a pipeline that would run north into France and from there to northern markets and/or east into Italy. However, the proposals never previously had much economic rationale as gas flows over the smaller, existing connections between France and Spain were predominantly north-south rather than south-north. In effect, the lack of interconnection was not a limitation as there was insufficient commercial demand to warrant increased capacity, even if the argument for the pipeline could be made on security of supply grounds.

Any such pipeline would also run into problems as soon as it crossed the French border as the French gas system itself lacks interconnectivity between south and north. The former is supplied primarily by Mediterranean LNG terminals, while the north is more part of the north-west European gas system. But, even in the north, there is a lack of interconnectivity with other European markets.

In the REPowerEU plan, Entsog, the European Network of Transmission System Operators, which made the plan’s assessment of critically-needed infrastructure, notes that there are “no significant gas capacities available from France to Germany”, and observes that France and Spain both odorise gas in their transmission systems, while countries in north-west and central Europe do not. This is a barrier to trade between systems, owing to infrastructural and regulatory constraints.

Entsog argues that Germany in the first instance needs to accelerate its planned LNG terminals at Eemshaven, Wilhelmshaven and Brunsbuettel. But to utilise fully west European LNG facilities for central and east European markets, two other elements are required: a deodorisation plant to facilitate gas flows west-east from France to Germany; and gas infrastructure reinforcements to increase export capacity from Belgium to Germany.

Major investment would thus be needed in France to make a major Spain-France interconnector viable by extending its reach into north and central Europe.

Spanish surplus

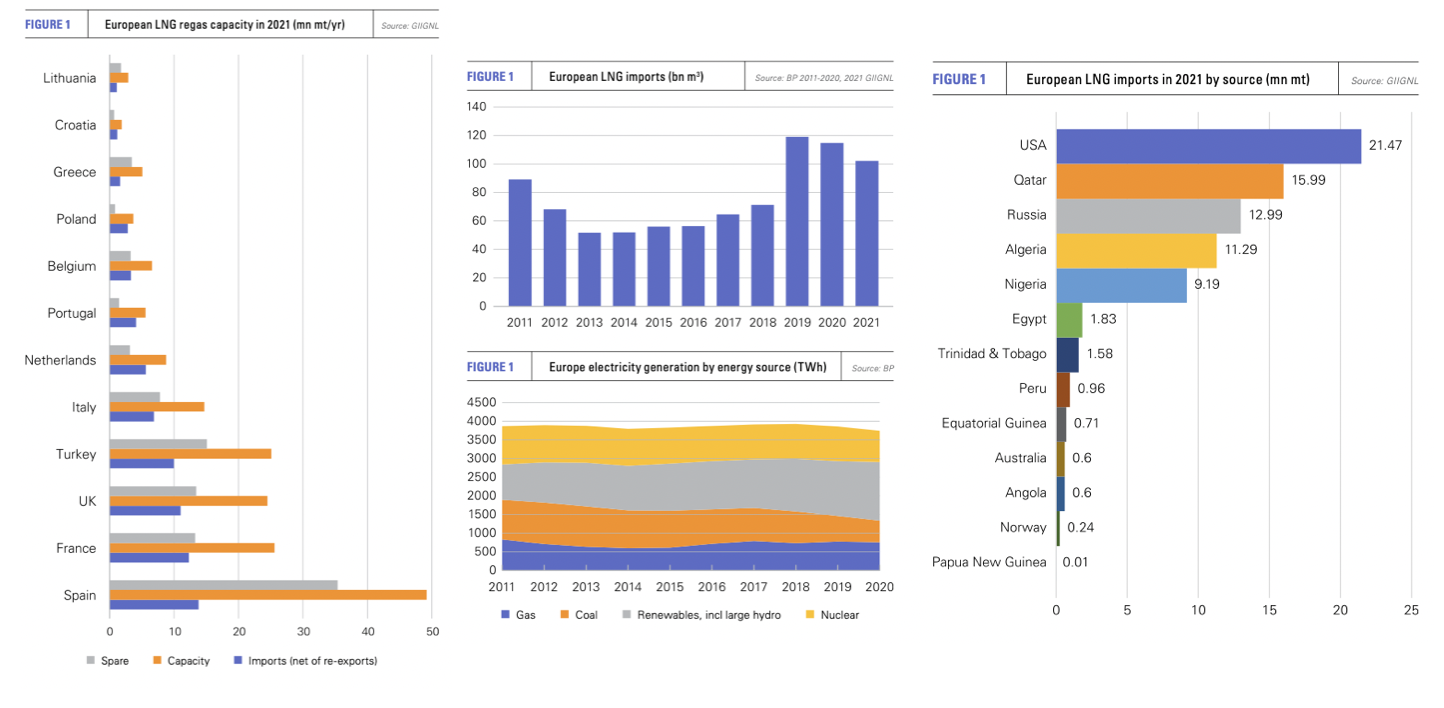

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has changed that calculus, but not the physical challenges such a pipeline would face. Instead, a new proposal to take advantage of Spain’s excess LNG import capacity and its pipeline connections with Algeria has been proposed. Spain has 49.2mn mt/yr of LNG import capacity spread across seven terminals, including the mothballed El Musel facility, representing nearly two fifths of the EU’s total LNG import capacity. In 2021, it received gross imports of just under 15mn mt, leaving ample spare capacity.

Italian gas grid operator Snam and Spain’s Enagas have already signed a memorandum to assess the feasibility of a pipeline linking the two countries. This would be a subsea pipeline running along France’s Mediterranean coast to make landfall in northern Italy. The idea certainly makes sense in that Italy is heavily dependent on Russian gas, particularly in the north, while southern France is not, and a subsea pipeline could avoid the lengthy permitting and construction times likely to affect construction of a major onshore pipeline.

The idea of an additional cross-border infrastructure project on the Iberian Peninsula has also been highlighted as a potential first element of a hydrogen import pathway, connecting to the large solar-powered renewable energy potential of the Iberian Peninsula for hydrogen production. Portugal, for example, has already set the world record a number of times for the lowest-cost solar power globally.

It could also extend further to tap into the vast wind and solar potential of North Africa, which could feed into European markets either as electricity or green hydrogen, using new multi-purpose infrastructure built today with the short-term aim of using Spain’s spare LNG import capacity.

Is it enough?

Probably not, even though large and important parts of the infrastructural investments can be delivered relatively quickly. The fundamental problem is that there isn’t likely to be enough available gas supply even if the internal infrastructure is put in place to allow its efficient distribution. Although the EU’s pivot to LNG is galvanising new investment in liquefaction capacity worldwide, most of this will not arrive until the mid-to-late 2020s.

The European desire to increase LNG imports will almost certainly have to come in the short-term by drawing cargoes away from Asia, but this can only be achieved to a certain extent as LNG is deeply embedded in Asian energy systems. Japan, South Korea and Taiwan all depend on LNG for baseload power generation, while China has emerged as the largest LNG market in the world. The nightmare scenario for both Europe and Asia is a cold northern hemisphere winter this year, which would be likely to push global LNG supply to its absolute limits.

The European desire to increase LNG imports will almost certainly have to come in the short-term by drawing cargoes away from Asia, but this can only be achieved to a certain extent as LNG is deeply embedded in Asian energy systems. Japan, South Korea and Taiwan all depend on LNG for baseload power generation, while China has emerged as the largest LNG market in the world. The nightmare scenario for both Europe and Asia is a cold northern hemisphere winter this year, which would be likely to push global LNG supply to its absolute limits.

However, the REPowerEU plan relies on more than additional gas supply. The plan has three main components, the first of which is energy savings. Increased efficiency and electrification in the residential and industrial sectors are expected to save the equivalent of 49bn m3 of gas, while behavioural change on the part of citizens – in effect turning down the thermostat – is expected to deliver savings of an additional 10bn m3.

Increased renewable electricity generation from wind and solar are expected to displace 21bn m3 of gas demand. Fuel displacement accounts for 104bn m3, broken down as 10bn m3 additional pipeline gas, 50bn m3 additional LNG imports, 17bn m3 biomethane and the displacement of 27bn m3 of gas by hydrogen and ammonia, the bulk of which is to be imported (10mn tons versus 4mn tons of domestic production), all to be achieved by 2030.

Target uncertainties

Each of these elements has its uncertainties. Green hydrogen production costs need to fall a long way to become commercial, implying a heavy subsidy burden to develop markets for such an expensive fuel. Would-be importers face significant investment risk before a functioning domestic EU hydrogen market becomes a reality.

The wind turbine supply chain is already stretched and the REPowerEU plan is notable for raising the EU’s renewable energy target from 40% to 45%, but without mentioning any targeted increase for wind. The reason is that current deployment rates are only about 60% of that required to meet the 40% target, let alone 45%. The focus in the new plan, therefore, falls on hopefully more realisable targets for solar capacity.

Efficiency savings including behavioural change are real wild cards. Can citizens really be persuaded to turn down their thermostats en masse?

More broadly, there is little doubt that high gas prices will have a significant demand dampening effect, but the role played by gas-fired generation in forming prices in the EU’s wholesale electricity markets means the substitution effect in terms of electrification, on which the REPowerEU plan depends, may well be undermined or at least retarded by high electricity prices.

A realistic assessment suggests a number of the elements of the REPowerEU plan will not deliver their targets. What then?

The plan itself recognises that a lack of natural gas will likely mean an extended period of coal use and delays to nuclear phase outs. Reducing gas use before coal makes little environmental sense, so in the event of fewer efficiency savings than expected and less displacement by renewables and green hydrogen/ammonia, the EU needs to ensure that the infrastructure is there to provide Europe with gas in the approach to 2030 when the LNG market will be better placed to deliver it at more affordable prices. In short, limiting the extent and duration of a recourse to coal is likely dependent on gas transmission system investment today.

The plan itself recognises that a lack of natural gas will likely mean an extended period of coal use and delays to nuclear phase outs. Reducing gas use before coal makes little environmental sense, so in the event of fewer efficiency savings than expected and less displacement by renewables and green hydrogen/ammonia, the EU needs to ensure that the infrastructure is there to provide Europe with gas in the approach to 2030 when the LNG market will be better placed to deliver it at more affordable prices. In short, limiting the extent and duration of a recourse to coal is likely dependent on gas transmission system investment today.