Energy spending takes a wrong turn [NGW Magazine]

The International Energy Agency has published its annual World Energy Investment report (WEI) covering investments made in 2018. For the second year running, investments in renewables fell, while spending on fossil fuel supply went up.

Introducing it, the IEA head Fatih Birol said that current investment trends show the need for bolder decisions to make the energy system more sustainable.

“Government leadership is critical to reduce risks for investors in the emerging sectors that urgently need more capital to get the world on the right track," he said.

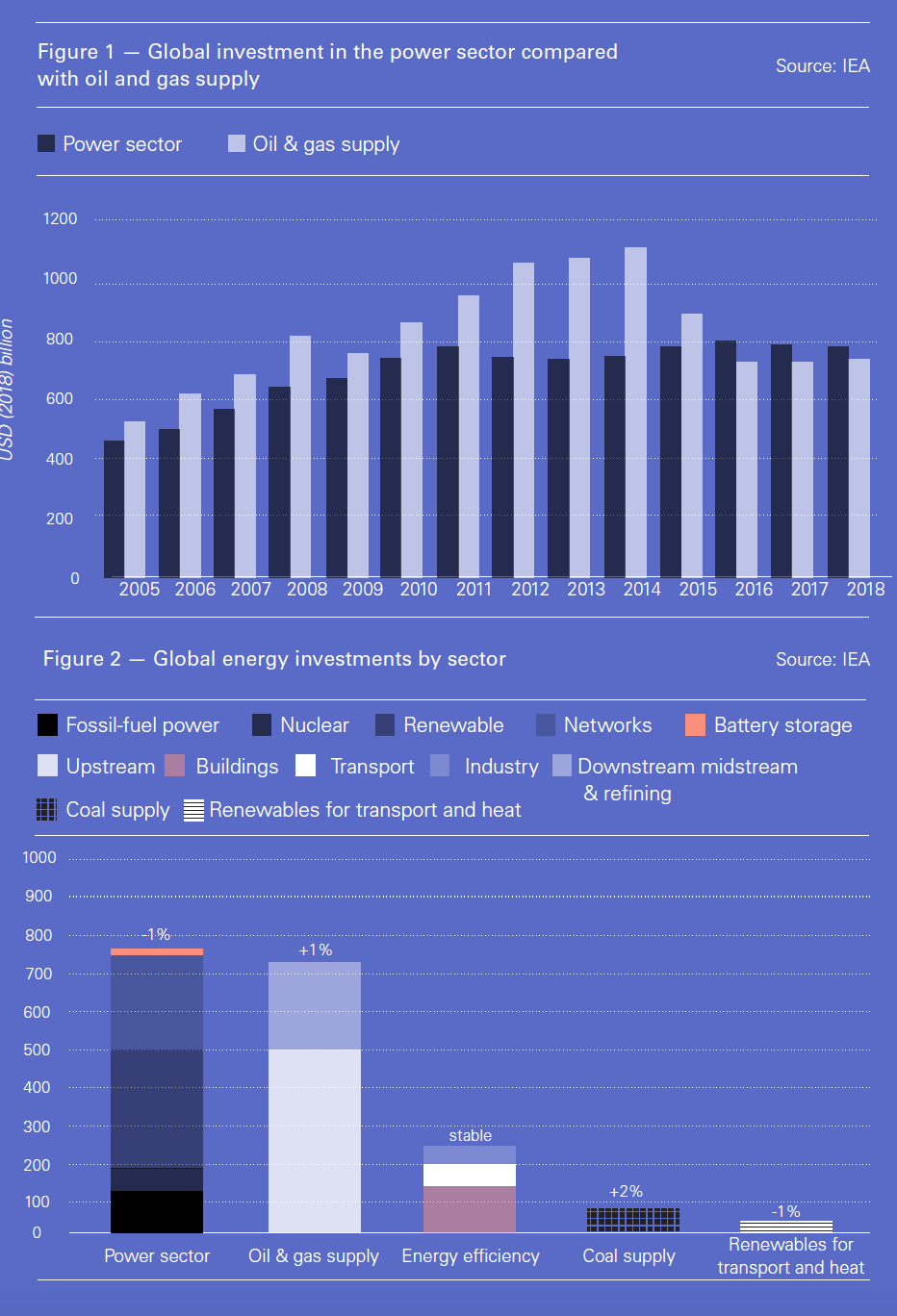

What may have prompted these comments was that even though global energy investments stabilised in 2018 (Figure 1) at about $1.85 trillion, after three consecutive years of decline, investments for energy efficiency and renewables stalled. The IEA identifies this as a clear signal of a growing mismatch between current trends and the paths to meeting the Paris Agreement and other sustainable development goals.

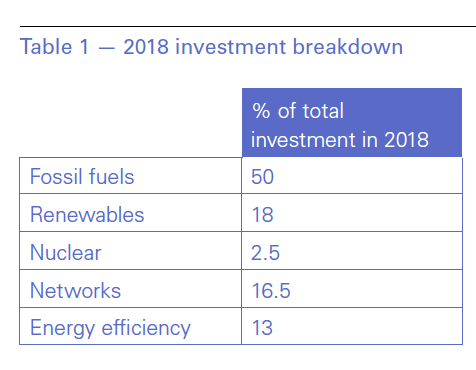

Investment in the power sector was again the largest, but down by 1%, while investment in oil and gas supply rose by 1% (Figure 2).

Power spending reflects the growing importance of electricity. In 2018 demand growth for electricity increased almost twice as much as overall energy demand.

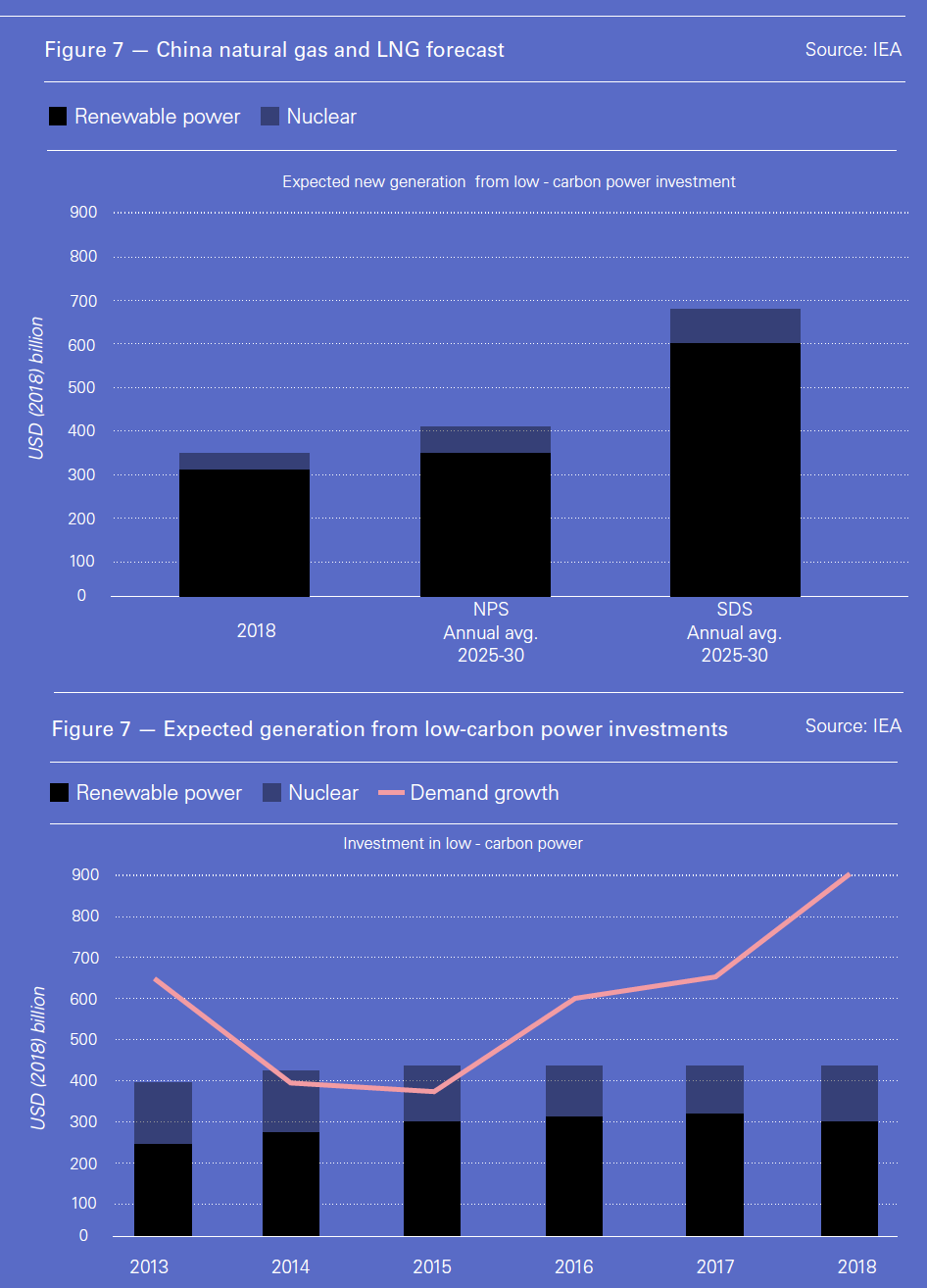

But the worrying development, in terms of environmental impact, is that global coal power generation investment and capacity continued to expand, particularly in developing Asian countries. Even more worrying is IEA’s conclusion that this is aimed at “filling a growing gap between soaring demand for power in Asia and a leveling-off of expected generation from low-carbon investments – renewables and nuclear.”

Proof of the challenge to reducing global emissions lies in the fact that investment in coal supply went up by 2% in 2018.

The way the results are presented in Figure 2 masks investment by fuel. This is shown in Table 1.

Investment in renewables was just over a third that in fossil fuels, which attracted half of all energy investment in 2018.

Energy investment by region

Energy investment by region

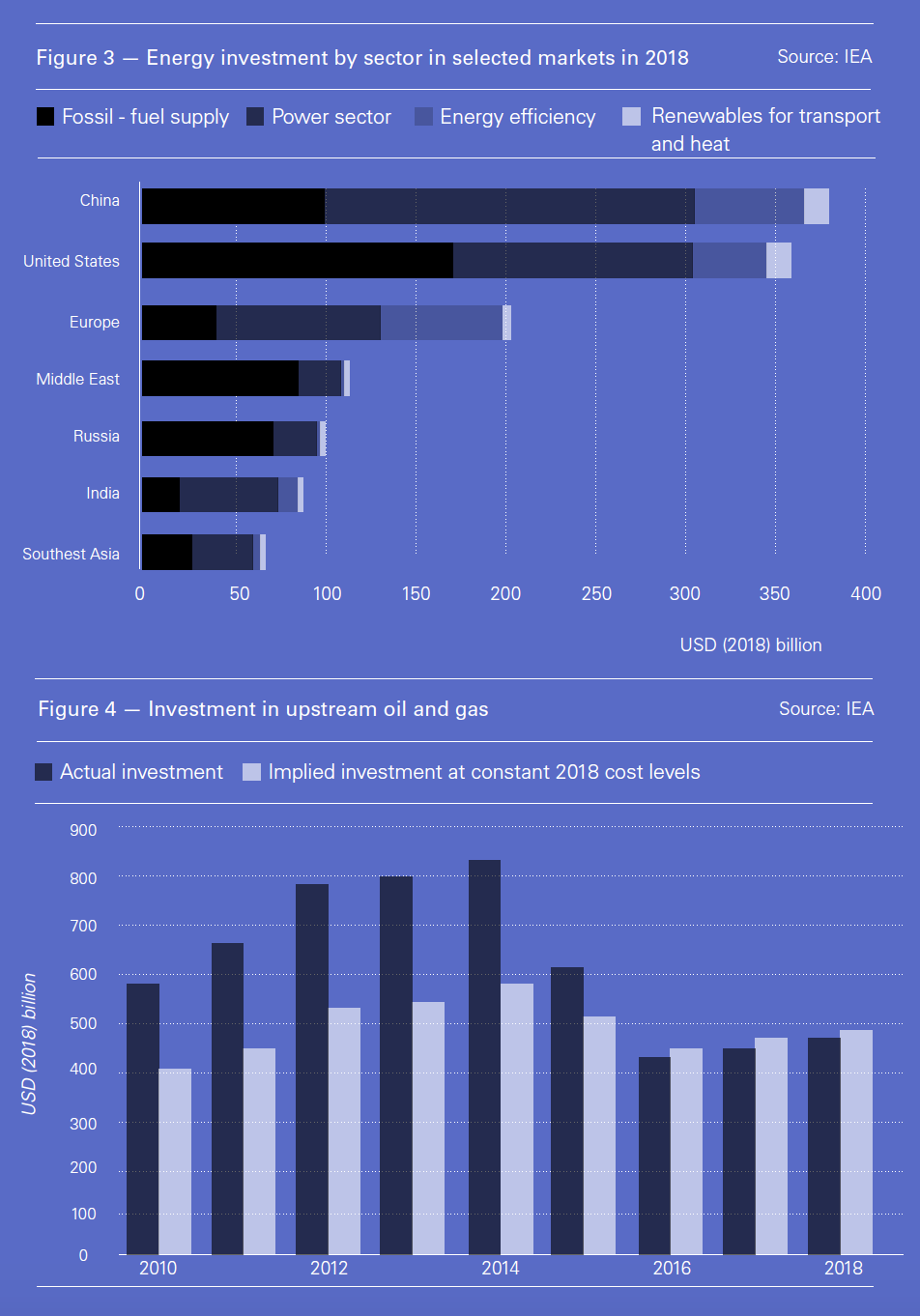

China remained the largest market for energy investment in 2018, with US a close second (Figure 3). The biggest jump in overall energy investment was due to higher spending in upstream supply in the US, particularly shale.

In China more than half of this energy investment, 57%, was on renewable supply, and only a quarter (26%) on oil and gas, the corresponding numbers for the US were 39% and 50%. Europe spent the most on energy efficiency: almost 35% of its spending went on this sector.

Of all major areas, India saw the biggest rise in spending – 12% over the past three years – with almost two-thirds of it invested in renewable supply in 2018.

This appears to be paying off, with India notching up another success in 2019. According to data released by its Central Electricity Authority, India generated 11.3 TWh of solar power during the first quarter of this year, a seventh (16.5%) more than in the previous quarter and a huge 57% jump from the first quarter in 2018.

Oil and gas

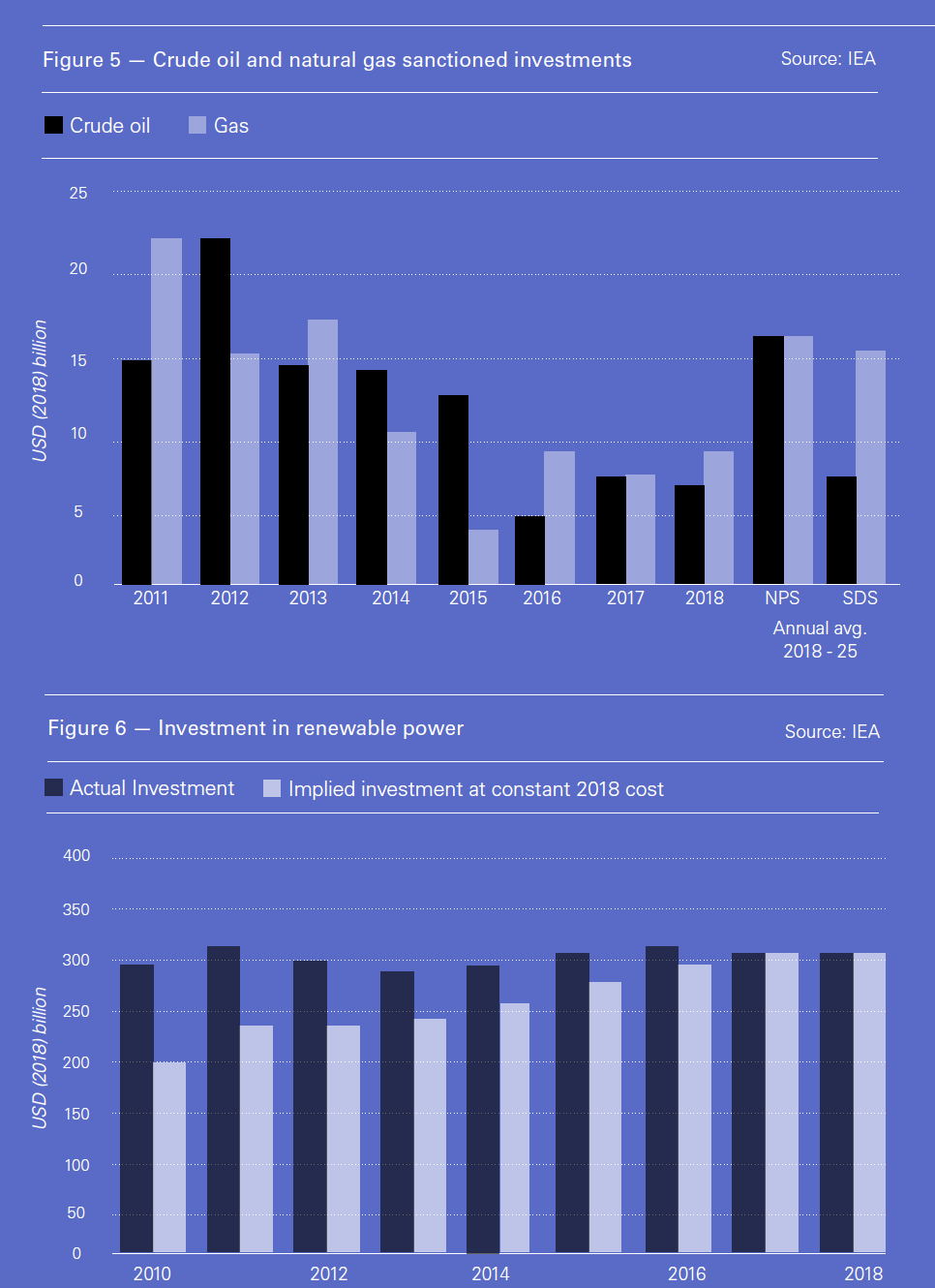

Investment in upstream global oil and gas supply increased by 4% in 2018 (Figure 4). However, it is estimated that overall, the industry managed to cut capital expenditure by about 30% the oil price crash – reflected in 2017 and 2018 investments – so it got more for its input.

But, according to the IEA, even the approvals for new conventional oil and gas projects fell short of what would be needed to meet continued robust growth in global energy demand.

This becomes evident when compared to spending required, according to the IEA, to achieve global energy levels envisaged in its ‘New policies Scenario” (NPS) and ‘Sustainable Development Scenario’ (SDS) (Figure 5) – the latter is compatible with the goals of the Paris climate change agreement.

In order to meet the demand growth for gas expected under both NPS and SDS, spending needs to almost double in the period 2018 to 2025. Gas has an important role to play in future, whatever the scenario, but to achieve this it requires substantially more investment.

The IEA says that the world is witnessing a shift in investments towards energy supply projects that have shorter lead times. In power generation and the upstream oil and gas sector the industry is bringing capacity to market in four fifths of the time it would have taken at the beginning of the decade. This reflects industry and investors seeking to better manage risks in a changing energy system, but also improved project management and lower costs.

In a fast-changing energy world, the major oil and gas companies are controlling spending and are putting priority on maintaining shareholder dividends at similar levels to before the oil price crash, in order to maintain investor interest and continued commitment against the ever-increasing pressure for divestment away from the oil and gas sector.

Renewables

In contrast, investment in renewable power slowed down in 2016 and 2017 and stalled in 2018 (Figure 6). In fact actual investments in renewable power fell for the second consecutive year. In addition, new renewable capacity added was the same as in 2017, making it the first time since 2001 that annual new installations failed to increase from the previous year.

This is a worrying development. The IEA states that output from low-carbon power investment is not keeping pace with demand (Figure 7). Based on WEI 2019, Birol sounded a warning. He said “Compared with 2015 when the Paris climate agreement was signed, the appetite to push low carbon investments and policies is slowly fading.”

According to IEA’s SDS scenario, twice as much will have to be spent on renewables in the 2025 to 2030 period to achieve sustainable development. The same also applies to investment in energy efficiency, which has also stalled. But current trends are moving in the opposite direction.

Concerns

According to BP Energy Outlook 2019 global energy demand is expected to increase by around a third by 2040, driven by improvements in living standards, particularly in India, China and across Asia.

This makes it imperative that global energy investment keeps up with demand, particularly in boosting renewables and energy efficiency if the world is to meet this demand while limiting temperature increase to less than 1.5 °C by 2100. There is little hope of reaching that, given spending patterns today: total energy supply investment needs to step up significantly. Without change, global warming will remain a serious problem. It is no coincidence that in 2018 energy-related CO2 emissions reached a record level, rising by 1.7%, as a result of increased primary energy demand, up 2.3% on 2017.

According to the IEA, energy supply investment needs to rise to meet goals under any scenario. This was summed up by Birol: “Energy investments now face unprecedented uncertainties, with shifts in markets, policies and technologies… But the bottom line is that the world is not investing enough in traditional elements of supply to maintain today’s consumption patterns, nor is it investing enough in cleaner energy technologies to change course. Whichever way you look, we are storing up risks for the future.”

This is even more so in the poorest regions of the world. The IEA stated that “They only received around 15% of investment in 2018 even though they account for 40% of the global population. Far more capital needs to flow to the least developed countries in order to meet sustainable development goals.”

The IEA states that in order to meet long-term sustainability goals in the SDS scenario, even with changing costs, low-carbon investment would need to grow 250% by 2030 in comparison to now.

The IEA also found that “public spending on energy research, development and demonstration (RD&D) is far short of what is needed. While public energy RD&D spending rose modestly in 2018, led by the US and China, its share of gross domestic product remained flat and most countries are not spending more of their economic output on energy research.” This was also identified by energy economist Dieter Helm in his interview, published in this edition of NGW, as a major shortcoming. He said much more needs to be spent on research and development in order to develop the new technologies required to combat climate change.

According to Birol the responsibility for energy investment rests on governments. If there were political will, then spending on renewables would not have been just about one-third of what went on fossil fuels, but substantially more. Governments need to act quickly to provide the required policy regimes to correct this situation and enable a faster flow of new projects. As Birol said, government leadership is critical. What is needed is clearer, smarter policy signals from governments.