EU carbon permits top €100/mt [Gas in Transition]

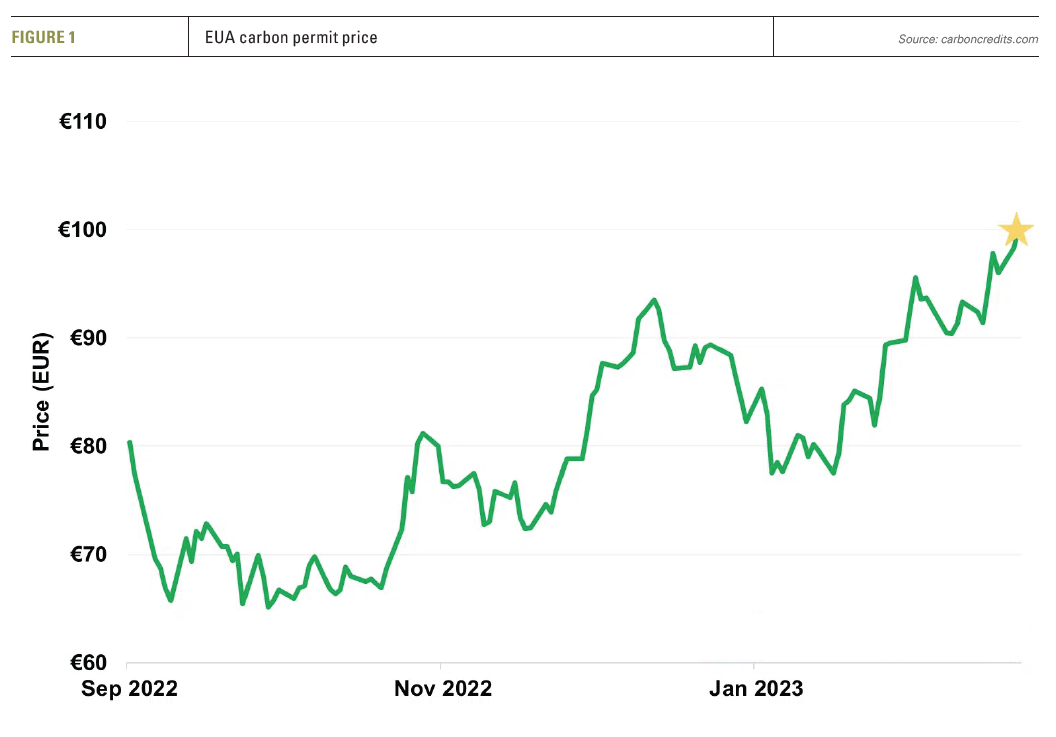

The price of EU carbon permits (EUA) exceeded €100 per metric ton (mt) of CO2 for the first time on February 21 (see figure 1). It has since come down to €87/mt of CO2 as a result of the turmoil in financial markets caused by concerns over bank failures.

However, this drop is likely to prove temporary. The general trend is upwards, with EUA futures prices trending towards €100/mt of CO2, for gas deliveries by the end of the year, and higher in future.

EU Allowance (EUA) is a financial instrument that allows the emission of one metric ton of CO2 for participants under the EU Emission Trading System (ETS). Participants in the scheme are obliged to buy carbon credits - with each one allowing the emission of 1 metric ton of CO2. At the end of each compliance cycle, all EU-ETS participants must surrender enough EUAs to cover all their emissions of that cycle. It is the cost that polluters in the EU, such as power plants, factories and aviation, must pay for each tonne of CO2 they emit. The ETS is effectively a cap-and-trade system and covers about 40% of the EU’s total CO2 emissions.

The EU-ETS is a cornerstone of EU's policy to combat climate change and its most important tool for reducing greenhouse gas emissions cost-effectively, helping the block meet its climate targets. It is the world's first major carbon market and remains the biggest one.

Since its introduction in 2005 it helped reduce the emissions of stationary installations in the EU, power plants and factories, by about 40% (see figure 2). A major contributory factor to this reduction is that the introduction of EUAs prompted utilities to switch power generation from coal to gas.

Some analysts believe that the high price of EUAs should incentivise investments in clean energy and technologies, including carbon capture and storage (CCS) and green hydrogen. However, that is not always possible, for example in ‘hard-to-abate’ heavy industries, such as cement, steel and chemicals – even in power generation, where gas is needed to provide baseload power.

In addition, with energy transition being a slow process, and long-term intermittency continuing to be a problem, it will take years before renewables and green hydrogen replace fossil fuels and for CCS to provide a cost-effective solution.

Another argument is that prices above €100/mt of CO2 could make green hydrogen and CCS commercially competitive. However, major EU manufacturers have warned of the impact of higher EUA prices on their business, competitiveness and ability to make investments, especially when the world is going through an energy and economic crisis. EUA prices at €100/mt of CO2 add about 45% to the cost of 1 m3 of gas consumed in the EU, at current gas and EUA prices.

EU strengthens ETS

In September 2020 the European Commission (EC) put forward a proposal to increase the EU's 2030 emissions reduction target from 40% below 1990 levels to 55% and to revise the ETS in order to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. The corresponding emissions reduction target for ETS was set at 43%.

These proposals had an immediate impact. As figure 1 shows, until then the EUA price was languishing at around €20/mt of CO2. After September 2020 it started rising and it has been rising ever since. In just three years EUA prices increased fivefold.

In July 2021 the European Council approved these proposals as well as legislation to strengthen the EU ETS. A key revision was to increase the pace of the reduction in emissions, with the overall number of emission allowances set to decline at an annual rate of 2.2% from 2021 onwards, compared to 1.74% in 2020.

Among other revisions, the EU also established a ‘Market Stability Reserve’ mechanism to reduce the surplus of emission allowances in the carbon market and to improve the EU ETS's resilience to future shocks.

In December 2022, the EU agreed that sectors covered by the ETS will have to cut their emissions 62% below 2005 levels by 2030 – a significant increase on the 43% target applicable previously. It also created a separate carbon market to include buildings and road transport, starting in 2027. Shipping was also added to the list in January.

The other big change is that emissions allowances issued by the EU will be reduced by an annual rate of 4.3% per year from 2024 to 2027 and 4.4% per year from 2028 to 2030, double the rate established in the July 2021 revision. By reducing the total number of carbon credits put out on the market on an annual basis, the ETS is meant to provide an incentive for companies to decarbonise their operations.

The other big change is that emissions allowances issued by the EU will be reduced by an annual rate of 4.3% per year from 2024 to 2027 and 4.4% per year from 2028 to 2030, double the rate established in the July 2021 revision. By reducing the total number of carbon credits put out on the market on an annual basis, the ETS is meant to provide an incentive for companies to decarbonise their operations.

One way to achieve it is by accelerating implementation of renewables. The REPowerEU plan targets a 45% share of renewables in final energy consumption. This was also voted by MEPs in September 2022, but the European Council is still to agree to it. Another is to reduce energy consumption. And that’s exactly what the EU will be doing. It agreed in early March to reduce final energy consumption by 11.7% by 2030 – this is legally binding.

In addition, it was agreed that free allowances will be almost cut by half by 2030 and phased-out entirely by 2034. These will be gradually replaced by a new carbon tariff at the EU’s border (CBAM), which should be fully in place by 2026, aimed to protect European companies from imports of cheaper products coming from countries with lower environmental standards. However, CBAM may protect the domestic market from imports into the EU from countries without adequate carbon pricing systems, but still risks leaving exports from the EU – subject to carbon pricing - uncompetitive.

The EU designed the revised ETS to ensure that a significant portion of the money raised from the sale of the credits goes towards the development of clean technologies and the decarbonisation of industry.

The EU Parliament (EP) and Council reached agreement on the new measures, paving the way for full adoption in April 2023.

Concerns

The EP warned that if companies do not decarbonise over the next few years, “there will be scarcity of emission allowances and that will increase the price”. It also claims that the ETS aims to “keep industry inside Europe and help it decarbonise”.

Clearly it is a difficult balance to strike. Increasing emission allowance prices undoubtedly drives emissions down, but the risk is that if such prices are too high, they may make European industry and manufacturing uncompetitive and may even drive them out. Already an increasing number of companies are seeking relocation elsewhere, such as the US, Middle East and Asia, where energy costs are lower.

At present, the EC seems determined to tighten the ETS and push carbon prices up. The goal to cut emissions 55% by 2030 from 1990 levels and achieve net-zero by 2050 appears to take priority over all else. However, rising carbon prices are a cause of political tensions in the EU and going over the symbolic €100/tCO2 threshold is likely to exacerbate these.

Consistently surveys show that most Europeans support transition to clean energy and are prepared to accept some changes in their lifestyles to help curb climate change, but also expect that no one should be left behind.

The Carnegie think-tank warned that “far from fulfilling its promise to foster citizen participation in climate policies, the European Green Deal, which aims to make the EU climate neutral by 2050, appears to have switched into technocratic crisis mode, effectively rendering the EU’s notion of a just transition more top-down.”

This risks provoking resistance from EU member states and citizens, despite the creation of a ‘climate action social fund’ to shield citizens from rising carbon prices. An example is the result of the Dutch provincial and Senate elections mid-March. A new populist party exploiting rural anger at government environmental policies – claiming that livelihoods are being sacrificed to the green transition agenda - has emerged as the biggest party by far, with enough seats to determine the makeup of the Senate, casting doubt over the government’s ability to pass key legislation, including its plans to slash emissions.

There are already calls from energy-intensive industries and some member states, for example Spain, for the EU to keep costs in check or risk damaging the fragile economic recovery.

A German push-back that – at least for now - blocked a ban on new combustion engines after 2035, has triggered other EU member states to rebel against laws that threaten industries, and beyond, potentially unravelling EU’s climate agenda. There is increasing pressure to ease energy prices for industry and the costs of climate action. Italy’s prime minister Giorgia Meloni went as far as to warn that the EU's growing environmental push, if poorly formulated, “risks damaging our economic fabric.” New laws under discussion, such as the update of EU’s ETS, which is due for approval in April, may now come under threat.

Carnegie argues that “there are no easy solutions to these shortcomings, and the climate–social justice–democracy trilemma will inevitably stretch EU policy coherence in the years ahead.” It recommends that the EU and its member states take practical steps to cultivate positive linkages between the three agendas, with full cognisance of the imperative of ensuring social justice.

Otherwise, the risk is that the Dutch elections may just be the beginning of renewed populist and EU member state resistance, “making the politics of energy transition more difficult and fraught.”