EU takes aim at Arctic oil and gas [Gas in Transition]

The European Commission (EC) recently unveiled a new Arctic Strategy that calls for the EU to expand its currently limited role in Arctic affairs. The strategy generated significant attention, largely as it included a proposal to ban the further development of the Arctic’s vast oil and gas reserves. Yet experts do not think the proposal can ever be realised, viewing it as fundamentally unworkable.

Published on October 13, the strategy acknowledges that the EU already gets a considerable share of its oil and gas supplies from Arctic fields in Russia and Norway, but says the bloc is “committed to ensuring that oil, coal and gas stay in the ground, including in the Arctic regions.”

“To this end, the commission shall work with partners towards a multilateral legal obligation not to allow any further hydrocarbon reserve development in the Arctic or contiguous regions, nor to purchase such hydrocarbons if they were to be produced.”

The EC said it wanted to convince all members of the Arctic Council to get on board with the initiative. The EU is currently not a member of the council, but has applied for observer status. The council is chaired by Russia, which, unsurprisingly, has roundly rejected the proposal.

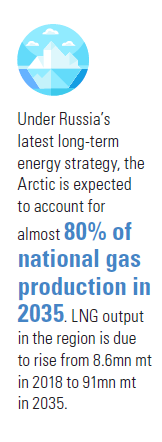

The Arctic represents the next frontier for Russia’s oil and gas industry, containing many of the country’s largest untapped oil and gas fields. Russian producers are banking on the Arctic for future production growth, as their once-large Soviet-era fields further south near depletion.

Norway, another council member, has also spurned the proposal.

“Resolutions from continental Europe call for stopping any activity above the Arctic Circle, but this will not work here,” Norway’s new prime minister Jonas Gahr Store said in an interview with the Financial Times. “Norway has the rights and duties to care for its economic zone and the activities in this region.”

He warned that Europe would struggle to achieve its green goals without further oil and gas investment, in line with Norway’s long-held position that oil and gas can help ensure energy security during the transition, while generating revenues that can be used to accelerate the deployment of renewables and other low-carbon technologies.

Elizabeth Buchanan, a polar geopolitics expert at Deakin University in Australia, says the proposal was “dead in the water before the ink was dry.”

“Arctic energy would include all fields above the Arctic Circle – so this significantly hits EEA partner Norway,” she tells NGW. “Norway is still unveiling new offshore Arctic hydrocarbon ventures, so one would think ‘consultations’ from Brussels missed entire states.”

An ill-timed proposal

The proposal came ahead of COP26 talks in Glasgow, where another, mostly European initiative to clamp down on oil and gas development was also launched. Denmark and Costa Rica are leading the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance (BOGA), whose core members, which also include France, Greenland, Ireland, Quebec, Sweden and Wales, have pledged to set end dates for oil and gas production in line with Paris Agreement goals, as well as commit to ending oil and gas licensing. However, notably absent from the group are any major oil and gas producers such as the UK, which despite hosting COP26, was non-committal.

The EC initiative also coincides with a severe gas crisis in Europe that has heightened concerns about energy security. A number of EU countries including Poland and Hungary have stressed the need for investment in gas to continue. As such, the ban will not only face international challenges but also “inner-EU fractional issues,” Buchanan says.

“We have been able to witness European energy insecurity in real time: just look to the gas crisis as Europe heads into one of its coldest winters on record,” she says. “States have demanded more Russian supplies, despite concerted efforts to diversify away from hydrocarbons and the Russian gas ‘weapon.’”

“We have been able to witness European energy insecurity in real time: just look to the gas crisis as Europe heads into one of its coldest winters on record,” she says. “States have demanded more Russian supplies, despite concerted efforts to diversify away from hydrocarbons and the Russian gas ‘weapon.’”

“Gas is the bridging fuel gas to any-energy revolution required to stay at beneath 1.5 and deliver on climate agreements,” Buchanan continues. “If Brussels wants to mitigate Russian gas, it should be crafting nuclear power agendas to support member states heading down that route – which is another sphere in which Russia asserts leadership.”

“While some governments have responded to the energy supply crunch with greater pragmatism, the EU has maintained a dogmatic stance against further oil and gas development,” Thierry Bros, energy expert and professor at Sciences Po Paris, tells NGW. “It risks losing its relevance. Brussels has zero power to decide whether the member states block oil and gas – that is the sovereignty of the state.”

Brussel's antipathy towards Arctic oil and gas development may make it harder for projects to secure financing from European banks, Bros says, but these projects will be able to get support from financiers in China and elsewhere in their stead.

Arctic push

On the EU Arctic strategy in general, Buchanan says the bloc’s policy in the region has remained largely consistent over the past few years. It wants to assert itself in the Arctic, but the main Arctic players may view this as an encroachment.

“There is a sense from Brussels that they want/need to be engaged in the region but there is also an overwhelming air of ‘what does Brussel's bring/why are they here’”, the expert explains. “This iteration of strategy at least attempts to articulate the basis for EU Arctic engagement.”

But she warns that “misfiring with a resource ban proposal (however, diligently crafted and environmentally apt) has crossed a line for many Arctic states who are resource exporters.”

“As such, the EU application for observership to the Arctic Council will likely remain on ice,” she predicts. “I think it has given ammo to Moscow to discredit a formal EU role in the region.”

KEY ARCTIC GAS PROJECTS

There are a number of large oil and gas fields already in production in the Arctic, mostly located onshore Russia. Gazprom’s giant Bovanenkovo field on the Yamal Peninsula, with a capacity of 115bn m3/year, is a major source of gas supply for the European market. There is also Novatek’s 17mn metric tons/year Yamal LNG plant, which supplies both Europe and Asia.

Novatek has plans for a series of other Arctic LNG projects, with the first one, the 20mn mt/yr Arctic LNG-2 terminal, due to come online in 2023. Gazprom also has major developments in the pipeline, including the Kharasaveyskoye field, set to start up in 2023, and the Tambeyskoye field at a later stage. Rosneft, meanwhile, is progressing its Vostok Oil project in the area, which while mainly oil-focused, could also eventually yield up to 50mn mt/yr of LNG, according to the company.

In Norway, meanwhile, the Arctic Barents Sea contains the Snohvit gas field that feeds into the Hammerfest LNG terminal, and several more discoveries have been made there.