Europe: from buyer of last resort to aggressive acquisitor [Gas In Transition]

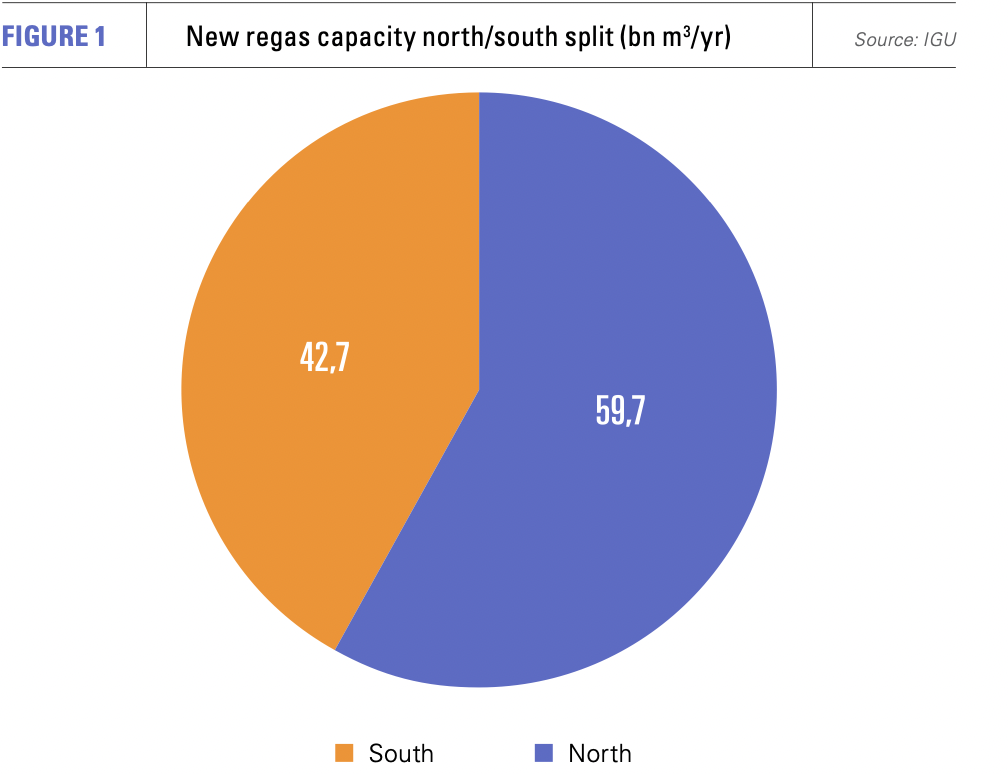

European LNG regasification capacity is expected to see one its fastest periods of expansion as countries turn to the liquified fuel as an alternative to Russian gas imports. According to a database published by Gas Infrastructure Europe, European regas capacity will rise by 102.5bn m3/yr to 361.8bn m3 by 2026, an increase of nearly 40% in just four years. The split for new capacity across Europe is just under 60bn m3/yr in the north and about 43bn m3/yr in the south (see figure 1). This marks a new and largely unexpected change for the global LNG market. From standing still with excess capacity and acting as the buyer of last resort when prices were low, Europe is set to become an aggressive buyer in a market under-prepared for such a sudden boom in demand.

European LNG regasification capacity is expected to see one its fastest periods of expansion as countries turn to the liquified fuel as an alternative to Russian gas imports. According to a database published by Gas Infrastructure Europe, European regas capacity will rise by 102.5bn m3/yr to 361.8bn m3 by 2026, an increase of nearly 40% in just four years. The split for new capacity across Europe is just under 60bn m3/yr in the north and about 43bn m3/yr in the south (see figure 1). This marks a new and largely unexpected change for the global LNG market. From standing still with excess capacity and acting as the buyer of last resort when prices were low, Europe is set to become an aggressive buyer in a market under-prepared for such a sudden boom in demand.

North-south imbalance

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

Regas capacity in Europe has gone through a number of distinct phases, starting with three terminals built between 1969 and 1972 all in the Mediterranean, serving Spain, Italy and France respectively.

In the 1980s and 1990s, northern Europe entered the game with the construction of the 13bn m3/yr Zeebrugge terminal in Belgium, but the majority of new capacity continued to be located in the Mediterranean, Iberian Peninsula or at least at some distance from the then developing and prolific North and Norwegian Sea oil and gas basins and the reach of Russian gas pipelines.

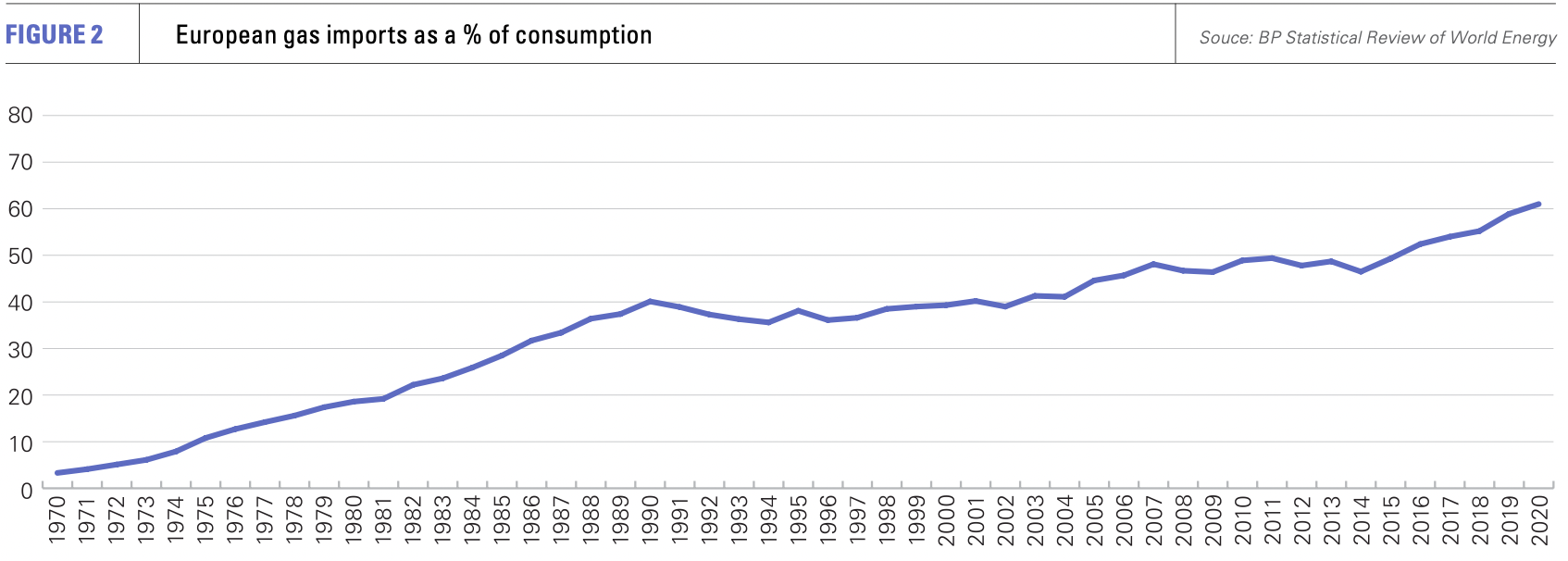

However, by the early 2000s – and at the high point of domestic European gas production – Europe’s dependency on imported gas had already risen above 40% and northern and eastern Europe had become increasingly reliant on Russia (see figure 2). There was a growing recognition of the need both to increase gas imports and diversify sources of supply as Europe’s own domestic gas production peaked and went into decline.

In the 2010s, the growing urgency of climate change also highlighted the important role gas would play in facilitating the phase out of carbon-heavy, coal-fired electricity generation, a process complicated by the adoption of nuclear phase out policies in Belgium and Germany and a general slowdown in the construction of new nuclear capacity across Europe.

Northern build out

Northern Europe started to build regas capacity in earnest from 2004 through to 2015, with some notable strategic differences.

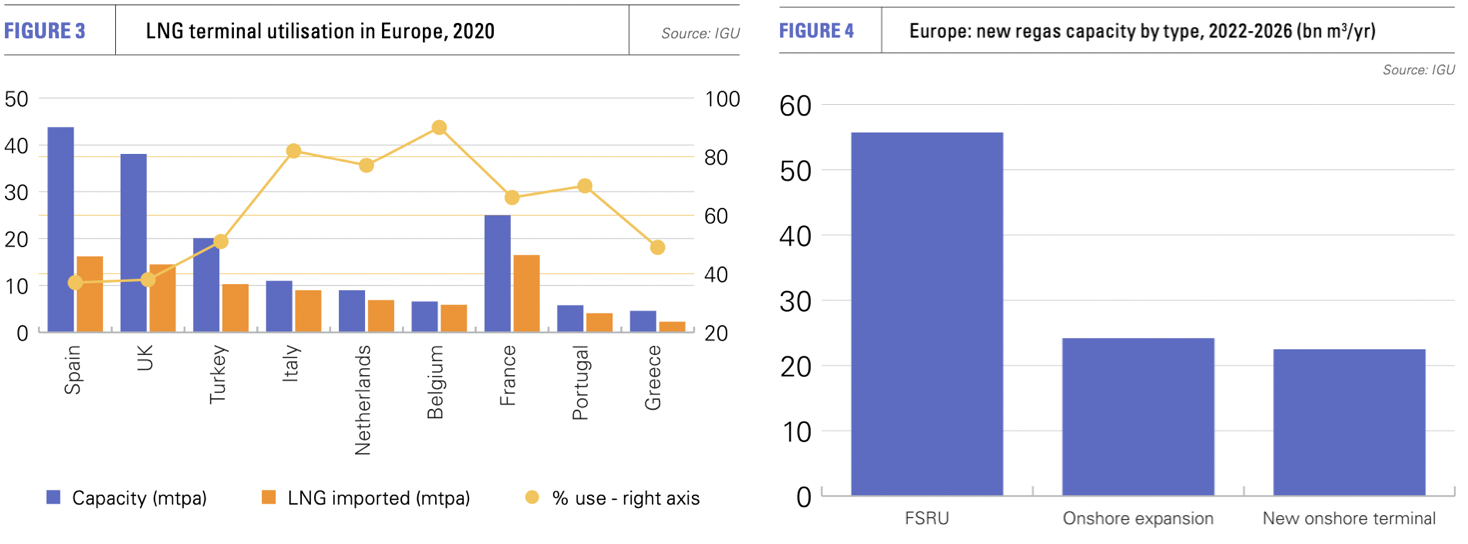

The UK, for example, built more LNG capacity than it needed, given its domestic production and pipeline connections with other European countries (see figure 3). The idea, now likely to bear fruit, was that the UK would not only meet its own gas demand with an increasing proportion of imports over domestic production, but become a conduit for surplus flows of regasified LNG into Europe via existing pipelines.

At the opposite end of the spectrum was Germany, which built no LNG terminals, resulting in its current heavy dependence on Russian gas imports. In 2020, Germany imported 56.3bn m3 of gas by pipeline from Russia against consumption of 86.5bn m3.

Golden banana

Europe’s regasification capacity is significantly larger in the south (211bn m3/yr) than in the north (150.4bn m3/yr) in aggregate.

However, southern LNG regasification capacity is distributed widely, along the Mediterranean from Turkey to Spain, and to Portugal, France and Spain’s Atlantic coasts. Capacity has increased fairly continuously. Southern capacity serves both Europe’s extremities and the ‘golden banana’, a region of high population density running from Cartagena in Spain, along the Mediterranean coast to Genoa in Italy.

In serving multiple disparate markets, it is much less well connected than northern LNG terminals to the centre of Europe’s gas grid in northwest and central Europe.

A prime example of its lack of interconnectivity is the infrastructural bottleneck in gas transmission capacity between the Iberian Peninsula and France. Spain, which is also served by Algerian pipeline gas, has seven LNG terminals with combined capacity of 67bn m3/yr, but only imported 20.9bn m3 of LNG in 2020. Spanish gas consumption peaked in 2006 at 40.2bn m3, substantially below its LNG import capacity and even more so when Algerian gas imports are taken into account.

There is thus substantial potential for regasified LNG to flow north. Proposals for MIDCAT, a pipeline which would double Spain-France transmission capacity and allow regasified LNG to flow north from Spain, were rejected by French and Spanish regulators in 2019, despite support from the EU. Prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the commercial case for the pipeline was weak, with the balance of gas flows across the French-Spanish border moving south rather than north.

The project is being re-evaluated, but would take five to six years to build and would then only deliver about 8bn m3 of gas into southern France. It would also need work on the French side of the border to connect it to a main European trunkline for onward transmission.

In contrast, while Spain arguably overbuilt its LNG import capacity, Italy underbuilt, relying on pipeline gas imports from Algeria, Libya and more recently Azerbaijan in its south and on Russian pipeline imports in the north. In 2020, Italy imported 12.1bn m3 of LNG, using most of its 15.5bn m3 capacity from three LNG terminals. This gives it little margin to replace its near 20bn m3 of Russian pipeline imports with increased LNG supplies.

Like Germany, Italy is now joining the rush to expand its LNG import capacity. Italian energy company Snam is looking to install two Floating Storage and Regasification Units (FSRUs) as early as next year to provide an additional 10bn m3/yr of regas capacity.

Blue banana

The core of Europe’s trunkline gas grid and demand lies in the north in the ‘blue banana’, a discontinuous urbanised area spreading across Western and Central Europe into northern Italy. This is less well served by LNG infrastructure in aggregate than the south because of the availability of domestic gas from northern Europe and Russian gas imports, but it is more concentrated and better connected to markets most dependent on Russian gas.

While regas capacity increased fairly steadily in the south, the north underwent a single decade-long period of expansion. Unfortunately, given the current situation, both areas are characterised by a hiatus in new completions from 2016 to the present in the north and from 2018 in the south.

The reason was that Europe’s position in the LNG market had settled into one of the buyer of last resort. LNG demand was being driven primarily by Asia, led by China. Only when that demand stalled, for economic or seasonal reasons, would Europe up its LNG imports as prices fell to competitive levels with pipeline gas.

Given energy transition plans which imply a reduction in gas use close to zero by 2050, Europe felt able to manage its growing dependence on imports, as overall demand fell, through the price competition provided by LNG. There was a need to improve the interconnectivity of the gas network and expand the reach of LNG, particularly in Eastern Europe. However, there was no need to maximise LNG imports, potentially creating stranded import assets, so long as they capped the pricing power of Russia’s gas monopoly Gazprom and other pipeline suppliers.

All this, of course, depended on the reliability of Russian gas exports, the supply side of which in volume terms looks as secure as it ever did. What Europe failed to bargain for was the political crisis precipitated by Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine.

Shortcuts to LNG

From being the buyer of last resort, European looks set to turn to LNG as a principal means of securing baseload gas, alongside a major expansion of its regasification capacity, in a very short time span.

The quickest two means of developing new import capacity are FSRUs and expansions of existing onshore facilities, plans for which in many cases were already being assessed, the primary question being the level of need and timing.

FSRUs are easier to site than onshore terminals, allow more land and port flexibility, and have lower capital expenditure requirements. They can also be relocated, which is likely to be a significant consideration based on the possibility that Russian gas regains its political acceptability at some point and that the EU’s energy transition plans imply steadily declining gas demand.

As a result, of planned new LNG import capacity in Europe from 2022-26, 56bn m3/yr is expected to come from FSRUs, 24.2bn m3/yr from expansions to existing onshore facilities and 22.5bn m3/yr from new large onshore terminals. The majority of new onshore terminal capacity only comes at the end of the 2022-26 time horizon, owing to the dearth of new build plans prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the length of time onshore LNG terminals take to build.

The planned four-year timetables for Germany’s 12bn m3/yr Stade and 8bn m3/yr Brunsbuettal onshore LNG terminals are ambitious, reflecting fast-track support from the state. Nonetheless, a planned 2.2bn m3/yr FSRU at Willhelmshaven is likely to be the first onstream.

FSRU market to tighten

The FSRU market was already showing strong growth before the Ukraine crisis. The number of floating and offshore regas terminals had grown from just one in 2005 to 27 as of February 2021, when there were a further ten facilities under development worldwide, mostly non-European.

The proportion of floating facilities to onshore terminals has been rising steadily, aided significantly by the willingness of ship owners, such as Golar LNG and Hoegh LNG, to build FSRUs speculatively for charter. There can be little doubt that the market for FSRUs post-Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will be unusually strong, driven not, as in the past, by periods of low LNG pricing, but on security of supply grounds, despite relatively high LNG pricing.

This is likely to create a shortage of FSRUs and prompt significant new building.

There are a number of ways of acquiring FSRUs; chartering unused vessels -- around 10 were being used as LNG carriers in 2020; chartering FSRUs whose contracts are ending; ordering newbuild vessels; or converting LNG carriers.

New-build construction takes two to three years and that timeline may become extended as the order book grows. As the number of large FSRUs is relatively small, and LNG tankers available for conversion tend to be older and thus smaller, newbuild appears likely.

Germany has entered the market aggressively, with the government in April announcing that it would release €2.94 billion to lease three large FSRUs. The government has subsequently indicated it may also support the lease or construction of a fourth. The first will be sited at Willhelmshaven and the second potentially at Brunsbuettal to provide early LNG supply. The other two could be located in northern cities such as Stade, Rostock, Hamburg or in the Dutch city of Eemshaven.

Based on the Gas Infrastructure Europe database, European countries are looking for 14 FSRUs by 2026 (see figure 4), with Germany only attributed one, rather than the three to four for which Berlin has said it will provide support.

Meeting growing demand

Europe’s pursuit of FSRUs and its greater pricing power could take vessels away from other planned LNG import projects around the world, for example in Asia and South and Central America.

Yet an extended jump in LNG demand, driven by Europe, looks a certainty as existing capacity with the right onward transmission links is maxed out and new import capacity brought onstream.

However, suppliers will struggle to meet rising demand in the 2022-2026 period, as it will only be in 2025/26 that both Qatar’s major expansion of its liquefaction capacity and large new LNG developments in the US – many of which have yet to reach final investment decisions – are completed.

This year only about 25bn m3 of new liquefaction capacity is expected to come on-stream, which means Europe will have to attract cargoes away from Asia, and will likely pay a high price to do so.

As a result, the European Commission’s declaration that the bloc will cut its Russian gas imports by two-thirds, or roughly 100bn m3, this year and end them completely “well before 2030”, looks ambitious. Increased LNG imports are only one element of that plan, albeit a critical one, but the unexpected nature of the supply shock means both the supply and demand sides of the market need time to adjust and build new infrastructure, even if they do so at the fastest possible pace.