Europe raises ambitions for hydrogen backbone [Gas in Transition]

European gas transmission system operators (TSOs) have once again broadened the scope of their plan for a continental hydrogen network, as the EU pushes for faster rollout of the low-carbon fuel as one of the tools for cutting Russian natural gas supply.

In its REPowerEU strategy published last month, the European Commission estimated that by raising annual hydrogen production and imports to 20mn metric tons by 2030, the EU could stop buying between 25 and 50bn m3 of Russian gas. The previous Fit-for-55 ambition was only 5.6mn mt of green hydrogen supply.

The European Hydrogen Backbone (EHB) initiative has responded in kind, and is now targeting a dedicated hydrogen-carrying network some 28,000 km in size by 2030, expanding to 53,000 km by 2040. That would be enough to meet 1,640 TWh of annual hydrogen demand in Europe within two decades. At the initiative’s launch less than two years ago, its size by 2040 was only envisaged at 23,000 km. And then in June last year, the ambition was raised to 40,000 km.

Today EHB now covers infrastructure across 25 EU member states plus Norway, the UK and Switzerland, and involves 31 network operators. This has grown from a mere 10 countries and 11 TSOs at its conception, when it was a Western Europe-only project. The cost of creating this network, 60% of which would be repurposed natural gas pipelines and 40% new, hydrogen-designed pipelines, has also ballooned €80-143bn ($87-155bn), up from an initial projected spend of €27-64bn.

Estimates for onshore transport costs for hydrogen remain the same as two years ago at €0.11-0.21/kg/1,000 km, which the initiative’s supporters say makes EHB “the most cost-effective option for large-scale, long-distance hydrogen transport.” Reflecting EHB’s expanded scope, the operators have also now worked out the cost of transport via subsea pipelines at a higher €0.17-0.32/kg/1,000 km.

Investment estimates for EHB vary greatly because of uncertainty and variability about compression system designs and costs, according to the paper, where operating costs depend a lot on pipeline sizes and designs, and the distance the hydrogen traverses.

Corridors

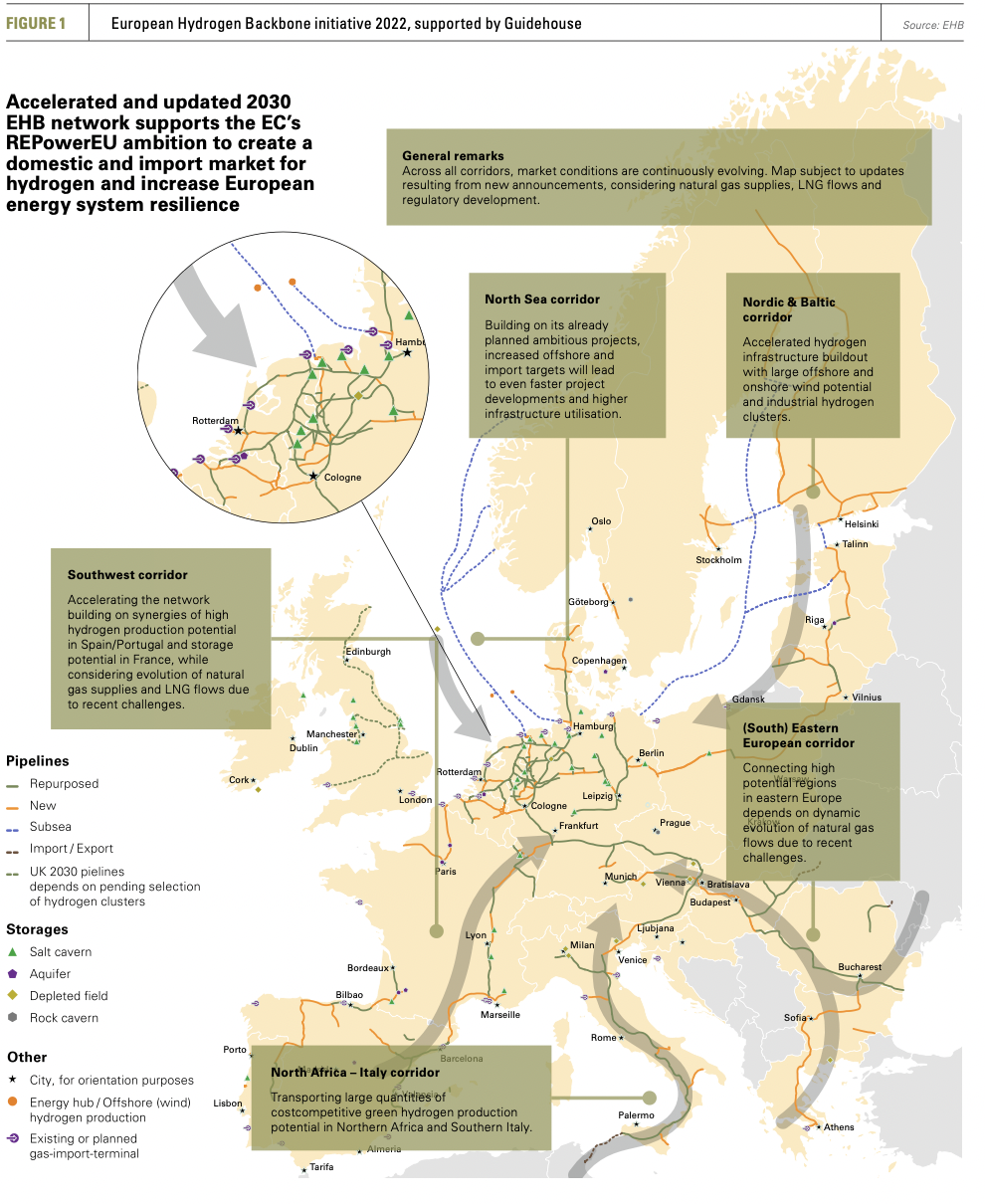

EHB also now envisages five key corridors for bringing hydrogen production from within and outside Europe to markets, all to be established by 2030. The North Africa-Italy corridor would bring supplies from Tunisia and Algeria through Italy to Central Europe, making use of existing pipelines in Italy, Austria, Slovakia and the Czech Republic, whereas the Southwest corridor would exploit the high hydrogen potential of the Iberian peninsula, and deliver the fuel through France and into west Germany.

A third, North Sea corridor would build on the Netherlands’ existing plans for a hydrogen port network, extending this system to ports in Belgium and Germany that are also expected to bring the fuel ashore. These ports could receive ship imports of hydrogen derivatives such as ammonia and methanol and liquid hydrogen, but also hydrogen from the North Sea, where both Norway and the UK are looking to capitalise on their offshore wind and natural gas reserves to become exporters of green and blue hydrogen.

A fourth Nordic & Baltic corridor would exploit offshore wind potential in northeast Europe and deliver the produced hydrogen to central Europe. This corridor would mainly comprise new pipelines, meaning that funding access and a fast permitting and planning process will be essential. The fifth South Eastern European corridor would meanwhile connect buyers in central Europe with southeast European states with significant renewables potential including Greece, Romania and Ukraine. The corridor would mainly consist of repurposed pipelines, although EHB’s participants note that the evolution of future gas supply in the region is uncertain, and that this would affect how the corridor emerges.

A fourth Nordic & Baltic corridor would exploit offshore wind potential in northeast Europe and deliver the produced hydrogen to central Europe. This corridor would mainly comprise new pipelines, meaning that funding access and a fast permitting and planning process will be essential. The fifth South Eastern European corridor would meanwhile connect buyers in central Europe with southeast European states with significant renewables potential including Greece, Romania and Ukraine. The corridor would mainly consist of repurposed pipelines, although EHB’s participants note that the evolution of future gas supply in the region is uncertain, and that this would affect how the corridor emerges.

These corridors would likely receive hydrogen through both pipelines and ship import terminals, depending on whichever is most viable.

Post-2030

While the EHB will initially serve industrial energy users, post-2030 it is expected that hydrogen will play a greater role as an energy carrier for other sectors such as heavy transport, e-fuel production, construction and long-duration energy storage and dispatchable power generation, according to the latest plan.

The plan also envisages new hydrogen trade being established with producers further afield like Namibia, Chile, Australia and the Middle East between 2030 and 2040.

“By connecting hydrogen producers with offtakers, this physical European hydrogen network could enable the creation of a liquid pan-European hydrogen market, thereby accelerating deployment of renewables, fostering market competition, and revitalising Europe’s decarbonised industrial sector,” the EHB plan states.

By supporting renewables deployment and electrification, hydrogen will make sure the European energy system is both affordable and secure, complementing intermittent wind and solar power with storage for when the wind does not blow and the sun does not shine. Notably, EHB is not meant to be an end-goal but a milestone, the report states, projecting significant further growth in hydrogen demand in the 2040s.

Policy

The EHB plan comes with policy recommendations. First, it calls on the EU to include in REPowerEU the establishment of hydrogen import corridors and other infrastructure requirements as “a political objective.” EHB’s supporters want to see a more integrated system for planning hydrogen, natural gas and power infrastructure at a member state level.

“Lead times for large-scale transmission, storage and port infrastructure implementation … can take up to 10 years,” the report states. “Integrated infrastructure planning must start today in order to send the right market signals, seize the upcoming investment windows, and have concrete infrastructure projects in place by 2030 and 2035.”

The plan also calls for regulatory provisions to incentivise the swift rollout of hydrogen infrastructure, including repurposed assets, and simplified and shortened planning procedures for renewable energy and hydrogen projects. “Flexible economic models” are also needed to spur investment, the report says, advocating for countries to subsidise upfront capital investments to reduce risks, and for the EU to employ the Connecting Europe Facility, the Important Projects of Common European Interest and Horizon Europe funds for the task. Lastly, both the EU and countries should forge partnerships with future hydrogen-exporting countries, pointing to Germany’s reaching out to Morocco and the UAE as an example to follow.