Europe’s perpetual crisis [Gas in Transition]

The energy squeeze on Europe caused by the energy crisis and the impact of sanctions on Russia as a result of its invasion of Ukraine has been relentless and, if anything, it is expected to worsen before it gets better.

Right now the situation is very precarious. It is no longer just high energy prices. With the European energy crisis intensifying and the likelihood of complete Russian gas cut-off increasing – Russian gas supplies to the EU are down to about 40-year lows - this winter looks potentially bleak, with the already very high energy prices likely to reach new highs. And as Foreign Policy puts it, “Russian [gas] outages and record-high prices threaten a winter of discontent.” In effect, Europe is in a perpetual state of crisis.

European energy security is at high risk in what is fast becoming the worst-ever energy crisis Europe has faced. The possibility of gas rationing and industry shut-downs is now real, with recession around the corner. German GDP growth stagnated in Q2 2022, while the UK economy contracted by 0.1%. The IMF warned that Russian gas cut-off would send some EU countries into recession. In fact, the Financial Times warns that “there is virtually no way to escape a Europe-wide recession.”

The EU has approved a voluntary reduction in gas consumption by 15% in order to conserve gas for winter. This will become compulsory if an emergency is declared. These are unprecedented measures, but it remains to be seen how successful they will be.

Europe is in a race against time to shore-up alternative energy supplies, from gas and LNG to coal, nuclear and oil, giving priority to energy security even at the expense of increased emissions. It is also accelerating the implementation of renewables. But will these be enough? It really depends on the weather this winter. With some forecasts predicting a cold 2022-2023 winter across western Europe, if realised, the energy situation could become quite dire. Europe is already facing strong competition from Asia to secure LNG supplies for winter, pushing prices further up.

With China in lock-down, its demand for gas and LNG has been subdued. But once economic activity rebounds, China will provide additional competition in an already over-stretched market.

Will there be a Russian gas cut-off?

Nord Stream 1 has been operating at 20% capacity since July 27. There are no signs of possible improvement, quite the opposite.

It requires five turbines to be operational for the pipeline to operate at full capacity. At present only one is. Following maintenance, a turbine has been returned by Canada to Germany, but Gazprom is refusing to take delivery because of current sanctions, even though Canada has issued a sanctions waiver.

Gazprom’s position is that "In the absence of official clarifications from the EU and the UK on the application of sanctions, it is not clear that the repair and transportation of gas turbine engines will not be subject to export restrictions."

In fact, on August 4 Gazprom said “The current anti-Russian sanctions prevent the successful resolution of the situation with the transportation and repair of Siemens gas turbine engines for the Portovaya compressor station."

Predictably, Germany is accusing Russia of blocking the return of the turbine. But without resolution, when the last operating turbine is next due for maintenance, fears are increasing that flow of Nord Stream 1 gas to Germany may be cut-off completely.

The situation is exacerbated by Gazprom’s refusal to utilise other pipeline routes to make up for the reduced gas supplies through Nord Stream 1, adding credence to accusations that Russia is “weaponizing” gas supplies.

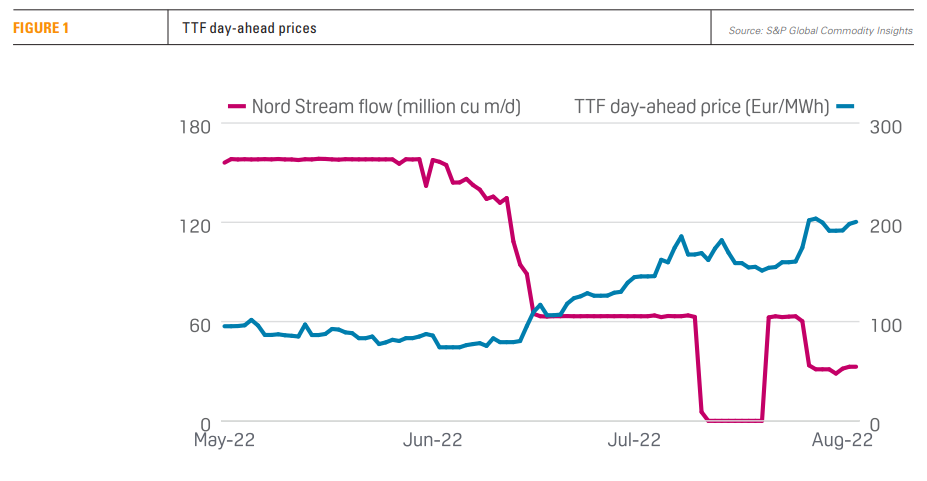

It is not surprising then that since this situation arose, gas prices in Europe have sky-rocketed (see figure 1). By mid-August the price of gas at TTF to be delivered in November was approaching €240 ($240)/MWh, over three-times higher than late-July – when Nord Stream 1 gas flows were reduced to 20% of capacity - and about ten-times higher in comparison to a year ago.

The consequences of complete Nord Stream 1 gas flow cut-off on EU gas prices would be severe.

Status of gas storage in EU

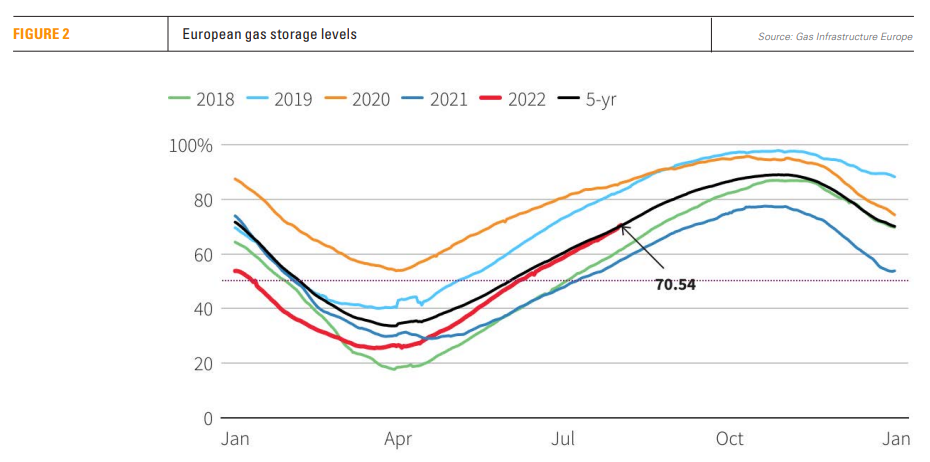

The EU set a target to refill gas storage to 80% of capacity by the end of October to provide a buffer for the expected high demand in winter months. By August 2, storage levels were just over 70% full (see figure 2), close to the five-year average and on track to meet EU’s target, but at a high cost estimated to reach €50bn to €55bn, about ten-times higher than the historical average.

This has been achieved by reducing demand, switching from gas to coal in some cases and increasing imports of LNG. Over the first half of 2022 the EU imported over 21mn tonnes of LNG, compared to just over 8mn tonnes over the same period in 2021. But uncertainties remain.

But a complete cut-off of Russian gas supplies next month would mean that the EU's gas storage target may not be achieved, with the risk that a cold winter could lead to gas supply shortages in Europe.

Germany’s predicament

Germany is one of the EU's most exposed states to further reductions in Russian gas supplies. As a result of the reduced gas flows from Russia, Germany is at phase two of its three-phase emergency plan. This is already causing major problems for its industry that consumes about 30% of Germany’s gas demand.

Phase three, will likely kick in if Gazprom cuts off Nord Stream 1 gas supplies completely. This will include gas rationing to industry, putting regulators, who will administer it, in a bind deciding how to apply and enforce it. Many companies are already applying for exemptions. At present, regulators are collecting data in an attempt to put together a shutdown list.

The government has just announced that German households will have to pay an additional energy levy, averaging €480/ear, to help energy companies cover the cost of replacing Russian gas supplies. Justifying this, the German economy minister, Rubert Habeck, said "The alternative would have been the collapse of the German energy market, and with it large parts of the European energy market."

A leading German bank, Commerzbank, has already warned that a serious shortage of natural gas supplies could trigger “a chain reaction with unforeseeable consequences” for the German economy, including recession. Natural gas is not just crucial for power generation, but it is also an important raw material for the German industry, such as chemicals and plastics that account for 15% of Germany’s total gas consumption.

Germany is getting ready for a difficult winter for industries and households as Russian gas supply volumes become increasingly difficult to predict and as the energy crisis drags on.

However, by July the country was on target to meet Europe’s gas demand reduction target, with gas consumption down by 15% compared with the average of the past five years. The IMF believes that this is the result of soaring gas prices.

In addition, by December operation of the first of four LNG floating storage and regasification units (FSRU) Germany has leased will start, enabling the country to import LNG directly.

But the IMF estimates that “a complete shutoff of the remaining Russian gas supplies would reduce GDP by almost 3% next year and raise inflation significantly. The effects could be even worse if the winter is particularly cold.”

Situation in the rest of Europe

Russia has been cutting off gas supplies to Europe faster than anticipated.

The EU's drive to secure alternative energy supplies is increasing competition for global gas and LNG resources, compounding the already high prices, impacting households and industry everywhere in Europe.

But the EU is also trying to address energy demand. On July 26, member states reached an agreement to voluntarily reduce gas demand by 15% between August 1, 2022 and March 31, 2023. If it succeeds it could reduce gas demand by as much as 45 bn m3, close to a third of Russian gas imports in 2021. The regulation also foresees the possibility that the European Council can “trigger a ‘Union alert’ on security of supply, in which case the gas demand reduction would become mandatory.”

But in order to reach such an agreement, the European Council agreed to “some exemptions and possibilities to request a derogation from the mandatory reduction target,” in effect watering-down its effectiveness.

EU member states agreed to update their national emergency plans by October to detail the demand reduction measures they are planning, and report regularly to the EC on the advancement of their plans.

The EU has also adopted other measures to improve resilience and security of gas supplies, including a gas storage regulation, the creation of an EU Energy Platform for joint purchases and measures listed in the REPowerEU strategy.

In any case, reduction in energy and gas demand is already happening as a result of high energy prices. As a result of weaker economic activity and less switching from coal to gas, the International Energy Agency (IEA) has lowered its three-year global gas demand growth forecast to 140 bn m3, in comparison to the 170bn m3 forecast in 2021.

Another development that can help improve Europe’s energy security is the backing by Germany’s Chancellor, Olaf Scholz, of a new gas pipeline, linking Portugal and Spain to France. He also suggested that there could be “other connections between north Africa and Europe that will help us to diversify our [energy] supply”. Might that include the East Med? Realisation of such projects would require the EU to accept long-term contracts, up to 2040 and beyond.

In the meanwhile, European industry is rapidly altering production processes to substitute electricity and other fuels for gas where possible, or importing semi-manufactured goods from outside the EU where access to gas is plentiful.

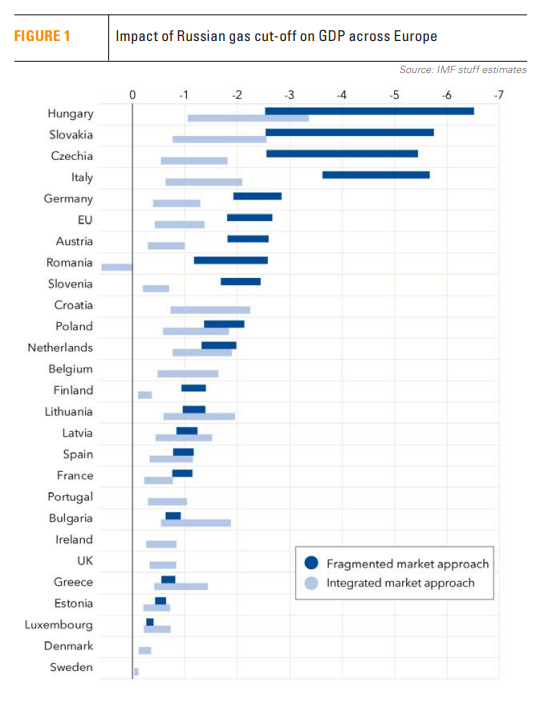

Following an economic impact assessment, the IMF concluded that “If EU markets remain integrated both internally and with the rest of the world, our integrated-market approach suggests that the global LNG market would help buffer economic impacts. That is because reduced consumption is distributed across all countries connected to the global market.” However, a fragmented market approach could have dire impacts on economic performance (see figure 3), especially for Hungary, Slovakia, Czechia and Italy, but also Germany and Austria.

The IMF recommends that beyond measures already taken, further action should focus on risk mitigation and crisis preparedness.

But undoubtedly the impact of increasing energy prices on households and the task of ensuring survival of industries on reduced energy supplies – with no end in sight – weighs heavily on European governments. As winter approaches, maintaining solidarity and public support of European policies is likely to be tested to its limits.

Implications

The heatwave and drought this summer are compounding the energy crisis situation in Europe. In fact, Europe has been suffering from drought throughout this year. And as if this was not enough, other shocks are exacerbating the crisis.

Despite its extensive nuclear power, France is drawn into Europe’s energy crisis woes. French nuclear reactors are down following cracks to infrastructure and a lack of water to cool the reactors, increasing gas dependence for power generation. This has sent the year-ahead electricity prices to an astonishing €535/MWh.

The water levels in the Rhine are so low that barges carrying coal and oil cannot travel up it, impacting supplies to power plants next to it and increasing Germany’s energy challenges and need for gas. By mid-August, year-ahead electricity prices rose to a record €420/MWh.

To cap it all, Norway warned August 8 that it would have to limit energy exports after its hydropower resources dried up – a first test of the willingness to share energy resources in Europe in crisis. Norway is one of the biggest electricity exporters in Europe, selling electricity to the UK, Germany, Netherlands and Denmark. That will increase pressure on the EU as it tries to diversify supplies.

In electricity production, despite its high emissions coal is coming to the rescue – at least temporarily. Germany is about to reconsider closure of its remaining nuclear plants. In addition, renewable electricity generating capacity in Europe is expected to increase 15% this year.

What could be good news is that the Netherlands is reconsidering its phasing out of gas production at the Groningen gas field. Ramping up production could certainly help the country and Europe – especially Germany – through these difficult times.

But even though helpful, these developments to secure alternative energy supplies and reduce demand will not be sufficient, still leaving a substantial gap between demand and supply that drives energy prices higher, contributing to increased inflation and cost of living and exacerbating the EU's economic downturn.

The problems may be compounded further if scarcity of energy supplies leads to reduced cooperation in sharing resources and increases protectionism.

Accelerating Europe’s transition to cleaner energy could provide the answers. But with intermittency still a problem, the road to cleaner energy will be long and arduous, with natural gas needed for a long time to come. Eventually Europe must recognise this and accept that new long-term contracts – greater than 10 to 15 years - required to justify the necessary investment in oil and gas E&P and infrastructure, will be essential.

And it will have to secure gas at substantially lower prices than now, if the burden to EU households is to be reduced to affordable levels and industry’s competitiveness is to be restored. It will also have to be dependable and reliable and not vulnerable to fast-evolving global geopolitics. Maximising production of European gas sources, such as East Med gas, ticks all these boxes.

All-in-all, this winter is likely to turn grim for Europe, with the need for gas increasing – at a time when Europe is committed to reduce reliance on Russian gas – and the risk that there will not be sufficient energy available to meet demand, despite EU’s message: “save gas for a safe winter.” In addition, the expected hike in prices and, in places, gas rationing later in the year are likely to cause social tension and unrest, even political upheaval. With not much new LNG coming online until 2026, next winter could also be challenging.

As the Columbia Energy Exchange has put it, “It is wartime… This is something that European politicians and consumers didn’t want to admit for quite a long time. It sounds terrible, but that’s the reality.” But “It’s not just high prices. There comes a certain point where there’s just not enough molecules to do all the work that gas needs to do. And governments will have to ration energy supplies and decide what’s important…This situation could last for several years.”