Fertiliser sector key support for Indian LNG demand [Gas in Transition]

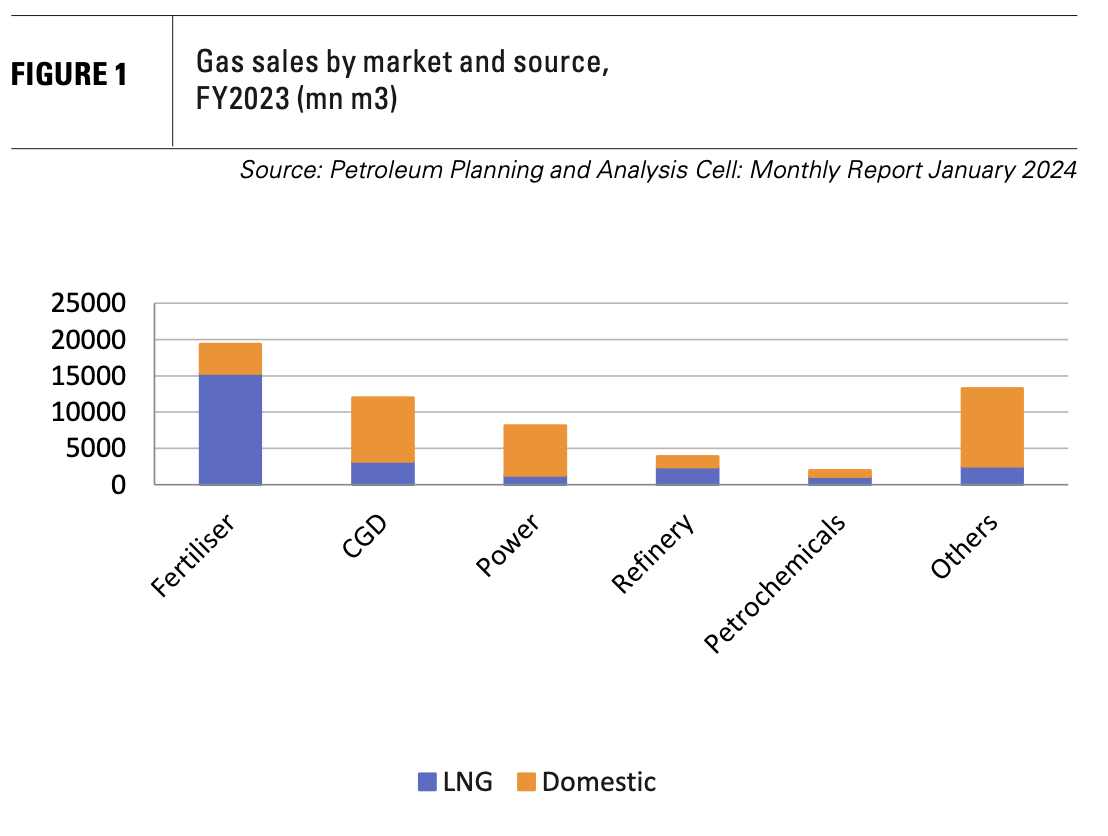

Indian LNG demand is unusual in terms of the proportion consumed by the fertiliser sector, with a relatively small amount now used to generate electricity (see figure 1). But with the government committed to increasing gas’s share of total primary energy supply from 6.3% to 15% by 2030, and with constraints in the supply of most other power station fuels, that could change.

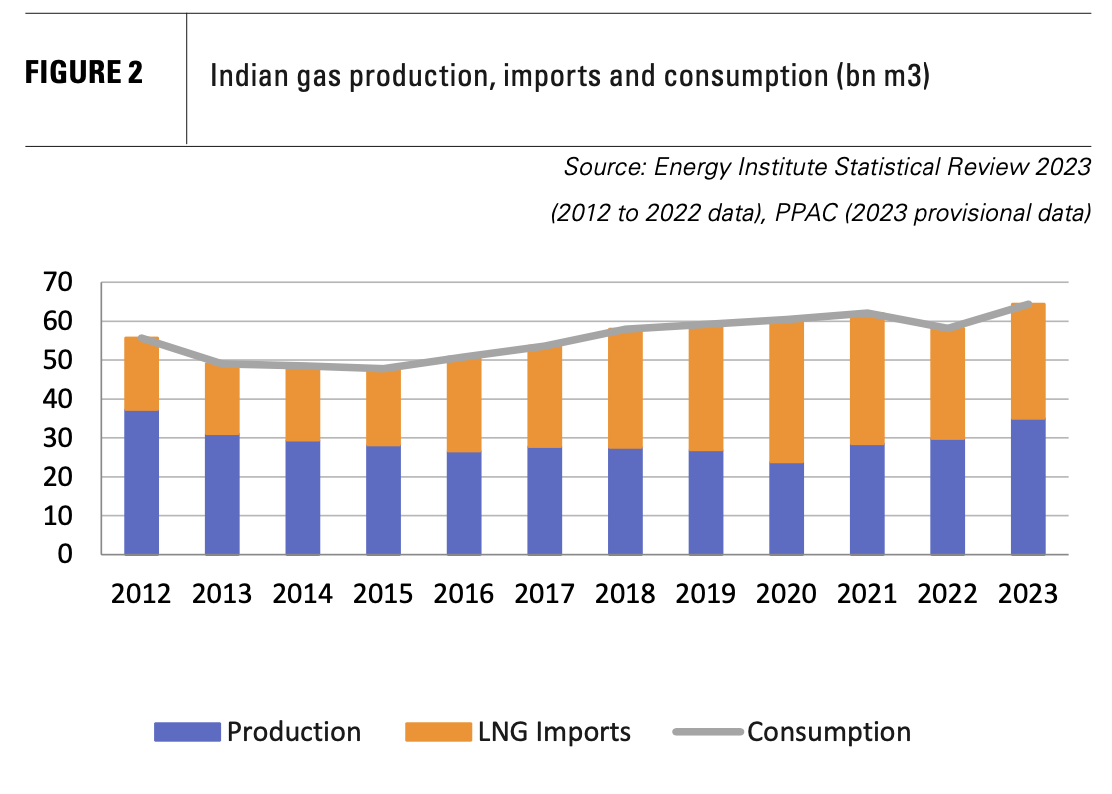

Indian LNG imports increased steadily in the 2010s. Arrivals more than doubled from 18bn m3 in 2013 to 36.6bn m3 in 2020, according to Energy Institute data. However, imports dropped to 28.4bn m3 in 2022, owing to the impact of COVID-19 and the soaring price of LNG.

As the economy has recovered and global LNG prices fallen, import levels have revived, particularly in the second half of 2023. Imports in 2023 totalled 29.34bn m3, according to India’s Petroleum Planning & Analysis Cell (PPAC). PPAC also reported that, at almost 2.5bn m3, imports in January 2024 were up 28% on the same month of 2023.

Limited alternatives to LNG

LNG imports have prospered in India in the absence of progress on plans to import pipeline gas or jump-start domestic gas production (see figure 2). Piped gas imports from Turkmenistan, Iran or other points west or northwest remain problematic because of the need to bring the fuel through Pakistan, while options to the east such as Myanmar offer relatively limited levels of supply.

Expanding domestic gas production has also proved problematic for fiscal, geological and other reasons. In fact, output fell from 37.3bn m3 in 2012 to 23.8bn m3 in 2020. Although production has bounced back, reaching more than 35bn m3 in 2023, questions remain over the more bullish projections for future output.

For instance, in February, the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) forecast that output would increase by 3.7%/year from 34.1bn m3 in 2022 to 94.1bn m3 in 2050. The EIA also projected that gas imports – all in the form of LNG – would increase from 37.2bn m3 in 2022 to 141.6bn m3 in 2050 to meet its forecast growth in gas consumption from 71.3bn m3 to 240.0bn m3 over the same period.

Industrial gas use drives demand

The EIA noted that its forecast increase in gas usage was driven by demand from industrials, and, in particular, from the fertiliser and oil refining sectors. It projected that industry, which already accounted for more than 70% of Indian gas use in 2022, would account for 80% by 2050.

The expectation that Indian gas use will become more concentrated in the industrial sector chimes with trends over the past decade. The fertiliser sector consumed 14.73bn m3 (25.7% of total gas sales) in the financial year ending March 2013 (FY2013). By FY2023, it accounted for 19.4bn m3 (33% of total sales), according to the PPAC, with more than 15.3bn m3 comprising LNG and only 4.1bn m3 coming from domestic output.

Fertiliser production thus accounted for almost 60% of all Indian LNG use in FY2023. The figures were similar for the ten months ending January 2024. Indeed, even more of the gas – 15.1bn m3 of 17.7bn m3 – comprised LNG rather than domestic production.

City gas demand has also increased over the past decade or so. It more than doubled between FY2013 and FY2023 to reach in excess of 12bn m3 and accounted for about a fifth of total gas sales in the latter year. Most of the gas came from domestic sources.

LNG-fired power out of favour

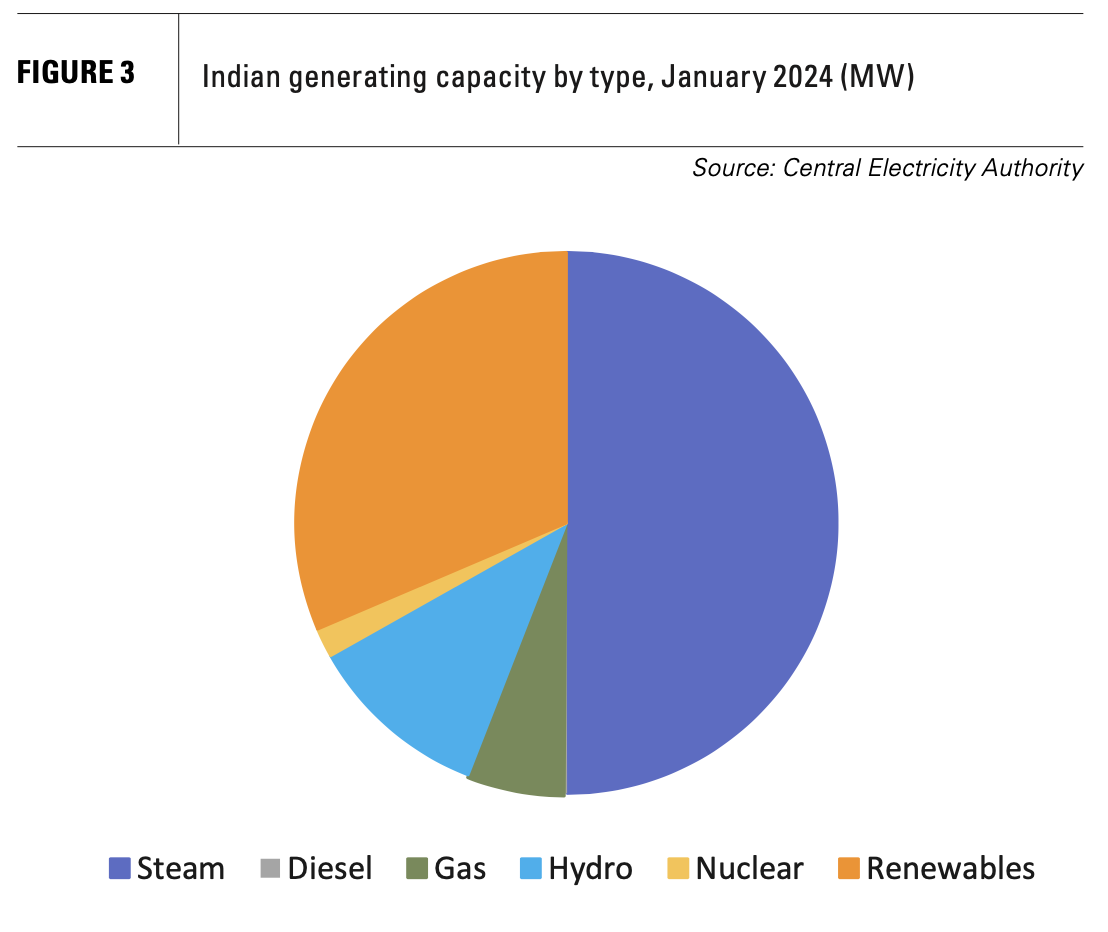

By contrast, gas use for power generation has fallen markedly (see figure 3). Sales to the sector fell from about 16bn m3 in FY2013 to less than 8.2bn m3 in FY2023, according to the PPAC. This came despite an increase in the amount of gas-fired capacity from 18,381 MW in March 2012 to about 25,000 MW in January 2024, with much of the additional capacity comprising efficient combined-cycle plants.

A lack of domestic gas and the high cost of LNG has stymied the use of gas for power generation. According to the Central Electricity Authority (CEA), domestic gas supplied to gas-fired plants peaked at 59.3mn m3/d in FY2011. By FY2022, gas-fired plants received only 22.62mn m3/d against a planned requirement of 101.5mn m3/d. Gas-fired generation plummeted from 87.5 TWh in FY2012 to 56.1 TWh in FY2022.

Gas-fired plants make up 6.2% of Indian generating capacity, but only 2.4% of total generation in the latter year, with the average plant load factor of gas-fired generators falling to 17.2%. FY2023 was worse still, although there was some upturn in the ten months to January 2024.

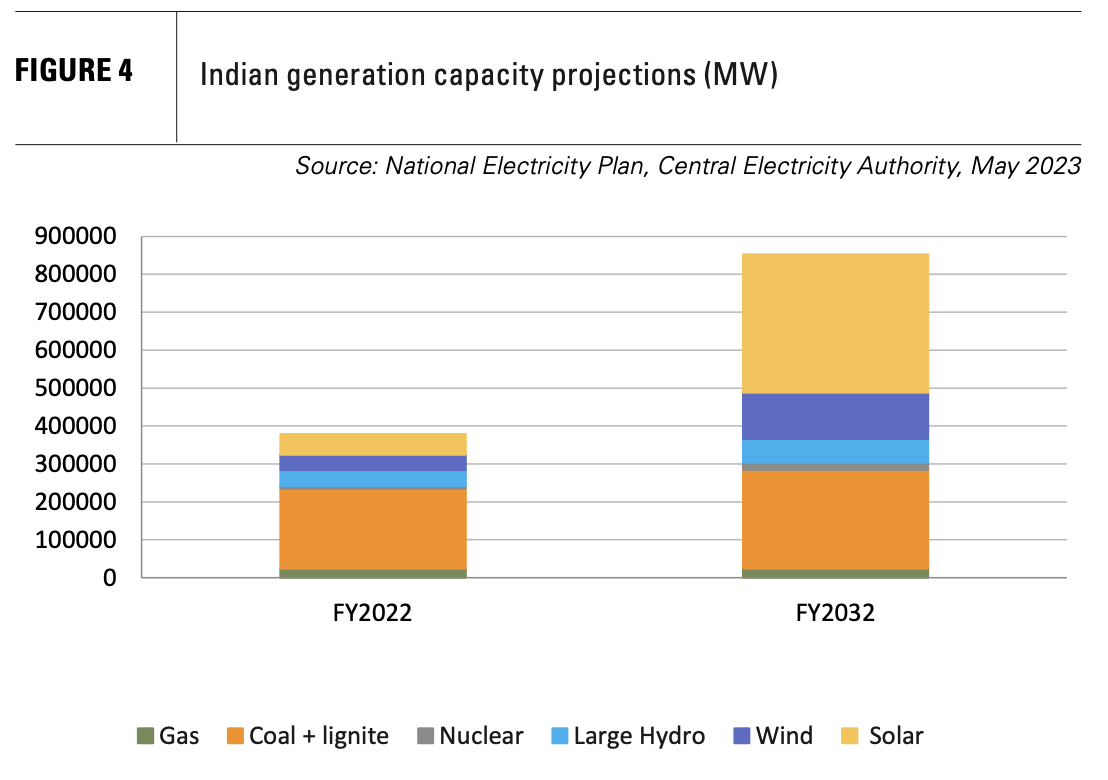

The National Electricity Plan (NEP) released by the CEA in May 2023 sees little change over the next decade. Gas-fired capacity is projected to remain at just under 25,000 MW over the period to March 2032 – none will be added, while the relative youthfulness of much of the plant means none will be decommissioned (see figure 4).

It will be used only sparingly at peak periods, with gas-fired generation projected at 34 TWh in FY2027 and 33 TWh in FY2032, when the fuel is forecast to account for only 1.3% of total generation.

It is hard to see how the government will meet its targeted increase for gas use in primary energy supply without a jump in both gas-fired generation and LNG imports. At the same time, a substantial increase in gas production (and thus increased supplies to generators) by 2030 seems optimistic, even with the $67bn investment programme announced by the government for the sector in February.

The accelerated rollout of city gas networks also seems unlikely to have much impact by 2030. But increased gas-fired generation would have some impact, especially if falling LNG prices makes its use more economically attractive.

Meeting future power demand

Gas is the only power station fuel not projected by the NEP to see a substantial – or indeed, any – increase in both capacity and generation over the period to 2032. Many of the projections for other power generating options are highly optimistic.

Despite poor implementation performance in the past and the long lead times involved, nuclear capacity is projected to almost triple from 6,780 MW in FY2022 to 19,680 MW in FY2032, with output in the latter year reaching 118 TWh.

Similarly optimistic is the projected increase in large hydroelectric capacity from 42 GW in FY2022 to 62 GW in FY2032, given that most potential projects involve very long lead times and face highly contentious issues relating to competing priorities for water use.

Issues relating to competing land use are also likely to have an impact on the projected increase in wind and solar capacity. The former is projected to increase from 40.4 GW in March 2022 to 121.9 GW in March 2032, and the latter from 54 GW to 365 GW. Overall renewable output (excluding large hydro) is projected in FY2032 at 934 TWh, or more than a third of the 2,665.7 TWh of total generation projected by the NEP for that year.

The projected hikes in renewable, hydro and nuclear output mean that coal-fired generation is projected to fall both in real terms and as a percentage of total electricity production.

In 2022, coal produced 1,380 TWh, or 74% of total Indian electricity. The figure is projected by the NEP to fall to 1,336 TWh or 50.1% of total generation in FY2032. But this would still require 1,054mn t of coal for power generation in FY2032, compared with 901.9mn t in 2022.

With coal production subject to the same competing priorities over land use as renewable energy installations, accessing the fuel will remain a far from easy task, even before addressing the growing debate within the country about carbon and other emissions.

Indian LNG demand could surprise

The fertiliser sector will remain a key buyer of LNG for some time to come if, as seems likely, it retains its current high level of subsidies. Indeed, as the EIA report observes, demand from the fertiliser sector alone could result in LNG consumption growing at a faster rate in India than any other major economy in the years to come. LNG purchases are in cases explicitly linked to the sector, including the 15-year contract signed in February between the local Deepak Fertilisers and Petrochemicals Corp. and Norway’s Equinor for about 0.65mn t/yr of LNG from 2026.

However, a resurgence in power sector demand for LNG cannot be ruled out. The NEP was finalised at a time of high spot LNG prices. This more than offset the efficiency advantage of gas-fired combined-cycle plants (at 55% compared with 40% for supercritical coal-fired units), resulting in the low priority given in the plan to gas-fired generation.

This could change owing to a combination of surplus LNG on world markets and burgeoning electricity demand in an economy currently growing at over 7.5%/yr. The limited ability of other power station fuels to meet the growth in the near to medium term could trigger substantial LNG demand, given a sufficient downward shift in LNG prices. Put simply, the 25 GW of under-utilised gas-fired plants could require about 40bn m3/yr of additional LNG to help keep the lights on.