From the Editor: Somewhere, over the rainbow [Gas in Transition]

It’s becoming increasingly clear that the world – rightly or perhaps with some level of naivete – has embarked on a yellow brick (well, rainbow brick might be a more apt description) road to hydrogen energy nirvana.

Hydrogen has been around since – well, since before the hydrogen-filled Hindenburg exploded into a ball of flame (and fame – ‘Oh, the humanity!’) in 1937 at Naval Air Station Lakehurst in New Jersey. It’s been used to fuel everything from internal combustion engines (as early as 1804) to NASA’s Apollo programme rockets. And Elon Musk’s SpaceX rockets may eventually use green hydrogen on future voyages to the moon – and beyond.

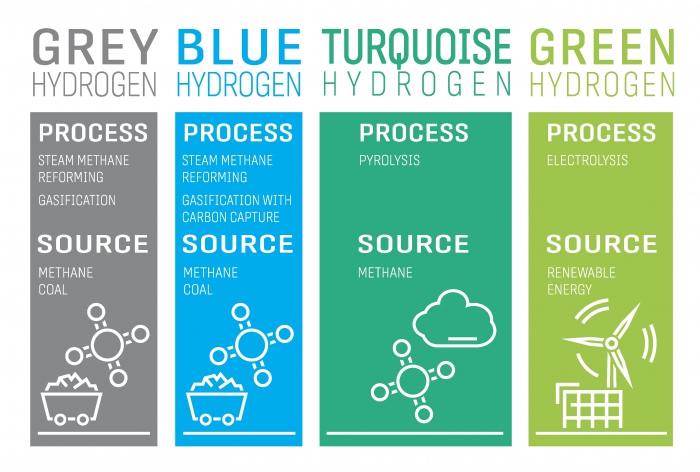

While everyone agrees that hydrogen emits no CO2 when it is combusted, its production produces varying amounts of the greenhouse gas, with the carbon intensity of hydrogen indicated by a rainbow of colours: grey for hydrogen produced from steam methane reforming (SMR) without carbon capture, blue for hydrogen from SMR with carbon capture, turquoise for hydrogen produced using methane pyrolysis and yielding solid carbon as a by-product, and green for hydrogen produced using electrolysis powered by renewable electricity.

Not all hydrogen is created equal

But this colour-wheel nomenclature indicates only the method by which hydrogen is produced – two molecules of blue hydrogen, or even green hydrogen, for that matter, can have widely diverging carbon footprints depending on how and where they were produced.

Earlier this year, GTI Energy, S&P Global Commodity Insights and the US Department of Energy’s National Energy Technology Laboratory joined forces in the Open Hydrogen Initiative (OHI), the express mission of which was to better define the CO2 impacts of hydrogen production, beyond the rainbow that is now used to define its pedigree.

“The world is rapidly preparing for aggressive decarbonisation, and having access to precise carbon intensity assessments is no longer ‘nice-to-have’ but required,” opined GTI Energy CEO Paula Gant on the launch of OHI in February 2022. ““With hydrogen applications increasing, more sophisticated measurement solutions are needed to assess the carbon intensity impacts of using this energy source. This world-class collaboration leverages the strengths of our respective organisations to develop thoughtful, market-ready solutions that will redefine how the world measures and benchmarks the carbon intensity of hydrogen production.”

In the months since the launch of OHI, a virtual who’s who of the hydrogen energy world has joined the movement, including Bill Gates and his Breakthrough Energy, the Bipartisan Policy Center, Stanford University’s Hydrogen Initiative, the Clean Hydrogen Future Coalition, the Renewable Hydrogen Alliance and Hydrogen Forward.

The natural gas producing community is also involved: OHI stakeholders now include global majors Shell, Equinor and ExxonMobil, US producers EQT, Dominion Energy and Duke Energy. Even the government of Alberta has joined, meeting a commitment of its own Hydrogen Roadmap to collaborate with others to develop science-based carbon intensity thresholds for hydrogen production.

“This collaboration will be important to establish carbon intensity threshold targets, definitions, and measurement and reporting standards,” Alberta Energy says of the initiative. “We look forward to working with OHI and its partners to develop a transparent and credible framework to measure the carbon intensity of hydrogen.”

Filling the hydrogen toolkit

The early work of the OHI is focused mostly on coming to grips with details of the various methods of producing hydrogen to understand energy and material flows and identify potential “emissions hotspots” of each.

Over the next 16 months, however, the OHI’s measurement toolkit will take shape, with demonstration projects tasked with identifying real-world applicability and credible carbon intensity values for a range of production methods.

An equitable comparison of carbon intensity at the facility level of hydrogen production could be a “game changer” for the hydrogen industry, the OHI says, leading to more precise and granular measurements, such as kilograms of CO2 produced with each kilogram of produced hydrogen.

S&P Global’s own hydrogen outlook sees global hydrogen demand growing to as much as 249mn metric tons by 2050 from just 70.4mn mt in 2020, with 90% of that growth coming from new demand sectors like heavy-duty transportation, steel production and long-term energy storage. But those sectors won’t look to hydrogen as a decarbonisation solution unless they can see an industry-standard emissions measurement and verification process that provides the market transparency they require.

In other words, “Don’t TELL me it’s clean; SHOW me it’s clean.”

That, in a nutshell, is where the rubber hits the road when it comes to the energy evolution. Many tools have been developed to get us to a low-carbon future, from carbon capture and storage (CCS) and renewable natural gas to alternative energies like geothermal and major deployment of more conventional renewables like solar and wind.

But proponents of many of these tools fail in showing how they can work, how they can bring about reduced emissions, how they can provide a vehicle on the road to decarbonisation. They merely proselytize that they are the “answer”.

The OHI, at least, has the ambition of laying out exactly what is needed to prove that hydrogen will, in fact, get us down that yellow brick road to a low carbon future. And showing us, in hard data, when we have arrived – if ever we do.