Gas and the EEZ Med [NGW Magazine]

To all appearances the growing tensions in the eastern Mediterranean are all to do with disputes over exclusive economic zones (EEZ) and therefore the control and exploitation of the resources of oil and gas that, by all indications, might enrich the region.

But that appears to be the only blessing in an area otherwise besieged with conflicts, teetering on the brink of war.

Following intervention by Germany’s chancellor, Angela Merkel, Turkey’s president Recep Erdogan agreed at the beginning of August to “pause” offshore surveys south of the Greek island Kastellorizo (Figure 1) andtoopena dialogue with Greece over their disputes.

Preparatory discussions to initiate such dialogue were in progress, but following the EEZ delineation agreement signed between Greece and Egypt August 6, Turkey pulled out of discussions and returned to its original offshore survey plans.

Given global developments, especially in the energy sector, are such conflicts justifiable, or is the region stepping back in time? Europe is moving away from fossil fuels and even though the transition to clean energy may take a long time, with the increasing penetration of renewables the world has entered an era of abundance of energy resources, including natural gas.

The problem at the heart of this whole saga is this: with plentiful cheap gas supplies in the global markets expected to continue for a long time, eastern Mediterranean gas is likely to continue to be too expensive to exploit commercially. The perceived riches locked in at the bottom of these disputed and fiercely-contested seas might never be economic.

In addition, the probability of significant hydrocarbons existing between Cyprus, Kastelorizo, Crete and Egypt’s EEZ boundary –the bone of contention between Greece and Turkey – is low.

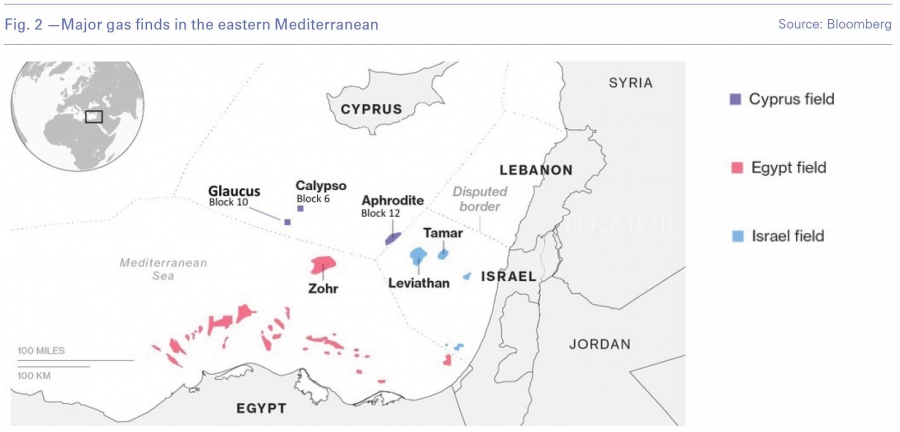

The areas considered to be of higher potential for hydrocarbon discoveries are uncontested waters: Egypt’s entire EEZ; the Levantine Basin that includes parts of Egypt; Israel; Cyprus and southwest Crete. Finds in these areas include Tamar, Leviathan, Aphrodite, Zohr, Glaucus and Calypso and southwest of Crete (Figure 2). The areas claimed by Turkey have mostly low probability of hydrocarbon presence.

This raises the question: what are the countries of the region striving for? Do they suffer from an unrealistic perception of the riches or are they reacting to Turkey’s determination to impose its will on the region? Whatever it is, natural gas appears to have little to do with it and it would be counter-intuitive for a war to flare up in a region with low potential for economic gas exploration and production.

Greece-Egypt EEZ agreement

Following the Greece-Italy agreement, the Greece-Egypt EEZ agreement is based on the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (Unclos), recognising island rights and reinforcing internationally-accepted maritime principles.

Welcoming the agreement, Egypt’s foreign minister Sameh Shoukry said it allows both countries to move forward in developing oil and gas reserves in their EEZs.

But before this can happen the EEZ must be delineated, including Cyprus. It is only after that that they will be able to divide their respective EEZs into exploration blocks, which eventually would enable the two countries to proceed with licensing rounds. It is only after that exploration and drilling can start.

But Turkey’s foreign ministry reacted immediately, denouncing it as null and void. It claims the deal falls within Turkey’s continental shelf and “violates” Libya’s maritime rights.

What has been agreed up to now

None of the EEZ claims in the east Mediterranean are clear cut, with the right completely on one side or the other. Even globally, experience shows that the application of Unclos eventually leads to agreements through negotiation, compromise and often referral to international courts. This region will be no different.

So far EEZ agreements have been reached by negotiations between directly involved parties: they are not declared unilaterally. Declarations ignoring the claims of other states, however tenuous these may be, cannot solve the problems and cannot prevail.

Formalised EEZ agreements reached so far are those between Cyprus and Egypt, Cyprus and Israel and Greece and Italy (Figure 3). All these agreements are based on Unclos.

Cyprus also reached an agreement with Lebanon, but this has not yet been formalised owing to EEZ disagreements between Lebanon and Israel.

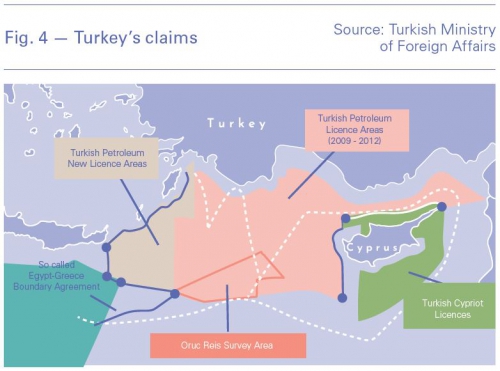

Turkey and Libya signed a maritime memorandum in November 2019, which defines a dividing line between the two countries without taking into account at all the rights of the islands such as Crete. The memorandum was condemned by the EU and the US as “counterproductive and provocative”. However, Turkey used this as the basis of defining its “continental shelf” claim (Figure 4).

The Greece-Italy maritime agreement, signed in June, was based on co-ordinates agreed in 1977 before the international implementation of Unclos. It appears to limit the influence to islands in the Ionian and deviate from the equidistance principle.

The Greece-Egypt agreement, on August 6, which provoked the wrath of Turkey, has only partly defined the EEZ boundary between the two countries – about 40% – between the 26th and 28th meridians (Figure 4). It does not extend to the Libyan EEZ and to the east it avoids the area affected by Cyprus and Kastelorizo. This seems to have been done at the request of Egypt, as it considers these issues to be complex, especially in relation to Turkey.

Also, the agreed boundary does not seem to correspond to the equidistant line between Egypt, Crete, Karpathos and Rhodes, but in roughly a 56%:44% division in favour of Egypt. However, it is a positive first step.

Even though the Greek-Italian and Greek-Egyptian agreements leave ambiguities, they also allow room for future negotiations on the remaining EEZ boundaries – and perhaps, in the end, for referral to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) at The Hague. However, they are of great importance as a basis for future negotiations.

These are realistic agreements, unlike the extreme Turkey-Libya memorandum that completely ignores the rights of islands, even Crete.

Room for negotiations?

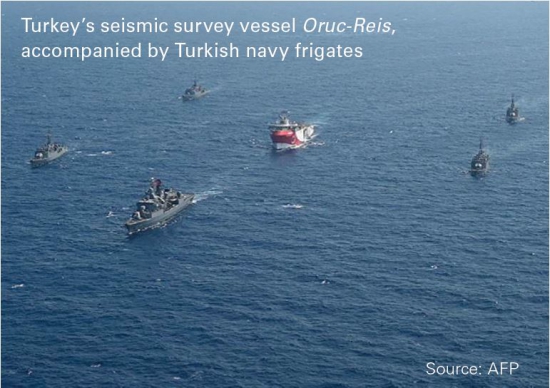

Following the frenzy of the first three weeks of August, Greece and Turkey have been brought back from the brink of naval confrontation. Turkey’s seismic survey vessel, Oruc-Reis, continued roaming the seas south of Kastelorizo (Figure 5) until August 23, but it was a Pyrrhic victory, if one can even call it that.

Turkey’s aggressive maritime pursuits have not won it any friends or any international support – quite the contrary. The international community in its entirety is condemning it. Led by the EU, notably France and Germany and with US and UK support, calls for settlement of these disputes through negotiations are growing stronger by the day. But so far this group has avoided stronger action, including sanctions.

As the situation has developed, Turkey has not even gained anything tangible through this belligerence. Some say that it has reinforced its claims to the contested areas, allowing the country to enter negotiations from a position of strength. But that plainly is not the case. These claims can be addressed only through negotiations, and, as and when these come, everything will be on the table, subject to the levelling influence of international law.

Greece’s restraint has faced considerable internal criticism but it has won Greece universal international support. Through this the risk of naval confrontation has been averted, possibly for the longer-term.

Discussions between the two countries may resume late August/early September, following de-escalation and German/US mediation. The challenge remains to agree an agenda for negotiations. The likelihood may be that – in the event of a deadlock – these disputes are eventually referred to international courts, possibly the ICJ, for mediation. This is the sensible way forward, that with EU and US help may prevail.

Greece welcomed the opportunity but made it clear that the immediate agenda should be confined to resolving maritime disputes. This was confirmed by its prime minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis. He said Greece intends to enter into dialogue with Turkey under strict conditions and within the framework set by international law on the issue of EEZ delineation. He went on to say that if the dialogue ends in disagreement, then the case should be referred to the ICJ.

Following Turkey’s strong reaction to the Greece-Egypt agreement, it is not now clear how Turkey intends to proceed. But on August 13, Erdogan said that the solution to these problems can only come through dialogue and negotiation, and he does not seek any "adventures" in the region. He proposed a "meeting of all the eastern Mediterranean states for a fair distribution of the region's energy resources". How credible these statements are will be seen shortly.

The only sensible way forward is dialogue and Germany’s continued mediation may eventually enable this. Nothing else is so likely to lead to the settlement of EEZ disputes.

At their joint meeting on August 20, French president Emmanuel Macron and Merkel confirmed that they “want the de-escalation of tensions and respect for sovereignty” adding that "we must have a positive agenda in order for Turkey to re-engage in dialogue with Europe." Macron reiterated that diplomacy without red lines does not exist, but military power without diplomacy does not produce results either.

Impact on Cyprus

To a certain extent, the potential dialogue between Greece and Turkey and the EEZ boundary agreement between Greece and Egypt sideline Cyprus.

The first may lead to an agreement between Greece and Turkey that could eventually impact Cyprus’ EEZ. And yet Cyprus is not party to this dialogue, other than indirectly through its close relationship and co-ordination with Greece.

This will be even more so if the dispute ends-up being referred to the ICJ, which is quite likely. The court will consider only the issues referred to it, jointly agreed between Greece and Turkey.

The Greece-Egypt agreement only addresses the EEZ boundary between the two countries, not accounting for Cyprus and Kastellorizo. This was done at the request of Egypt as it considers these issues to be too complicated. This leaves open questions that can be dealt with only through negotiations with Turkey.

In the meanwhile, Turkey is continuing and escalating intervention in Cyprus EEZ. It has issued a new Navtex and is proceeding with seismic exploration east of the island, in an area that includes Cyprus’ offshore blocks 2 and 3 licensed to two of Europe’s biggest producers, Eni and Total. This is a clear message that Turkey considers Cyprus a completely different issue, leaving the island in a vulnerable situation until a solution can be found to the Cyprus problem.