Gazprom looks inward [NGW Magazine]

Until recently, Gazprom downplayed the importance of the domestic market relative to gas exports but now the domestic market is in the ascendant while exports languish. There are plans for broad gasification of the country’s heartland; for the development of the petrochemical industry; and for expanding the natural gas vehicle sector.

Gas as a major source of revenue and geopolitical weapon

For a long time, Russia/the USSR had relied on the export of its gas and oil as a major economic and geopolitical activity. It was a source of hard currency and essential consumer goods from its East European satellites, reversing the traditional model of empires where the colonies supplied raw materials for their industrialised overlords. But after the collapse of the USSR, even its former republics became hostile and so had to pay up for oil and gas. There was little conviction in Russia that oil and gas prices could ever fall. And people in the Kremlin also believed that Russian pipeline gas would always be cheaper than LNG. The model, however, has come to face serious problems.

The problems with the old paradigm

After the Ukrainian crisis in 2014, Moscow’s relationship with the West worsened. It was not just the relationship with the US but also with Europe that had cooled. Sensing that Russian gas could face problems in the European market, the Kremlin clinched a deal with China, despite having been reluctant to do this for a long time. It was quite likely that considerable price concessions were made. It is true that Gazprom is planning an even larger pipeline to China – “Power of Siberia II.” But this is less to do with China’s great appetite for Russian gas than with opportunism. The European direction has also become less promising. Nord Stream II was almost finished when it was hit by US sanctions – and even though Gazprom will most likely finish the line, it will be of little help. First, it can fill only half the line. And second and more important, gas prices are in freefall. Gazprom is suffering massive losses for the first time in its history as a corporation and may be on the verge of a financial catastrophe. It has to pay about $4.5bn in total to Ukraine and Poland to settle arbitration cases over prices. That in itself would not be so bad if the gas price were higher. For the first time in Soviet and post-Soviet history, that is, possibly for the last 60 years or so, selling gas to foreign customers has become loss-making. And that is the point where Gazprom, possibly for the first time in its history, has turned its focus to the domestic market.

The home front

For a long time, domestic consumers had posed problems for Gazprom. While foreign consumers paid a hefty price for gas in hard currency, domestic consumers paid not only much less per kWh but also much more slowly. Gazprom relentlessly demanded its “pound of flesh,” even from the most destitute households. But even that had its limits. A case in point is the North Caucasus and Chechnya in particular: Gazprom had to subsidise the region on behalf of the Kremlin in order to avoid another bloody conflict in the area. But while Gazprom would have loved to forget about the domestic market completely for this and other reasons until just a few months ago, now everything is changing and Gazprom has embraced domestic customers with a new-found appetite.

Reports of Russians who saw their gas supplies terminated for non-payment have become a rarity on the internet. Moreover, Gazprom has announced an ambitious gasification programme for far-flung and rural regions. Gazprom supported gasification within Russia with the stress on those either in villages or the eastern part of the country. The programme is to run from 2021 to 2025.

Benefit for ecology: from gasoline to natural gas

Export problems have also had beneficial implications for Russia’s ecology. It would be wrong to assume that the desire to protect clean water, air and wildlife was missing in Soviet or post-Soviet Russia. But these considerations played only a very minor role in decision-making, despite catastrophic consequences. The Soviet government, for example, insisted on increasing cotton production in central Asia regardless of the drainage of major rivers in the area. The Aral Sea, once one of the biggest freshwater lakes in the world, and the site of a unique ecosystem, has now dried up and is mostly a desert, poisoned by pesticides from basically defunct rivers. There were some ecological improvements in post-Soviet Russia: for example, some species of fish and crustaceans re-emerged in places where they were thought extinct. But most were coincidental with the decline of Russian industry that reduced pollution. Most post-Soviet Russians saw air pollution as a Western obsession but these matters are now taken seriously, and the government has provided a considerable amount of funds for a natural gas vehicle market, instead of gasoline. The government wants to cover 60% of the cost of NGV manufacturing. It has also been noted that electric cars are more efficient than cars running on gasoline.

Even the Russian tanker fleet will be transformed in the future, and one recently-constructed tanker could operate just using natural gas, adhering to the strictest ecological standards. Finally, there is great interest in developing a Russian petrochemical industry fed by gas. Gazprom has signed a 20-year contract with Ruskhimal’ians, the “biggest in Gazprom’s history.” Part of the gas will be liquefied and part of it used as feedstock at a petrochemical plant. Plants of this sort will spring up in different parts of the country including the Amur in the far east; and northwestern Russia, around the Baltic. In addition a new “gasochemical cluster” is also planned for Bashkiriia and it is to be one of the biggest in Asia. Finally, vice prime minister Yury Borisov, has announced that he has “fallen in love” with the oil and gas chemical industry.

Broad implications for gas market

It was implied that the petrochemical products could be either consumed inside the country or exported. These changes – the move from selling gas abroad to attempt to use it for domestic use – are not just a Russian phenomenon, and may be seen in other gas-producing countries; at least this is the case with the US and also with some former Soviet republics. Uzbekistan could be here an example. Not so long ago, Uzbek officials tried to increase gas exports as much as possible, limiting demand at home by pushing consumers to use coal instead of gas. Now though with prices low they have switched tack and gone instead for domestic gas use, including the manufacture of petrochemicals and other value-added goods. One can only guess to what extent these moves will change the gas market. It all depends on global economic conditions. If the economic recovery is strong and demand for gas goes up, then plans to retain gas for the domestic market will evaporate and there will be little in the way of permanent change for the gas industry. Indeed, some Russian observers believe the gas demand slump is only a temporary phenomenon. Still, if the slump persists and alternative sources of energy, such as wind or solar power, increase their share of overall energy consumption, then more gas will stay within the home market.

|

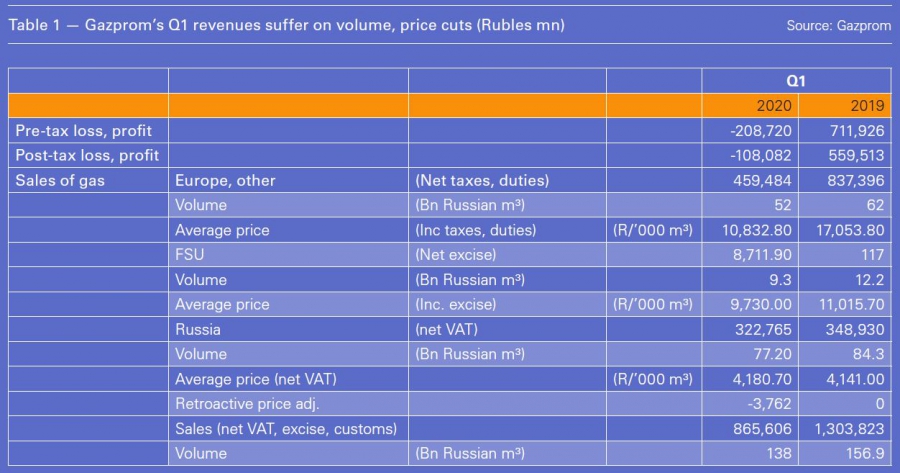

Difficult year for Gazprom Gazprom made a net loss of rubles 116bn ($1.64bn) on its trading in the first quarter, versus a net income of rubles 536bn in the same period last year, according to its accounts under International Financial Reporting Standards. It blamed the result on oil price-related impairments and ruble devaluation. It had to repay customers rubles 3.76bn in Q1 retrospective price adjustments, compared with zero the previous year (see table). It has also paid for transit capacity through Ukraine that it will not be able to use in full, as a result of under-deliveries in the first half of the year. There was also a slump in demand owing to a very mild winter, well-stocked storage facilities and a weaker global economy, which had been deteriorating since late in 2019. The state gas supplier also saw its profit on sales slump to rubles 293.5bn, from rubles 459bn in the same period last year. European gas demand took a hit in March as a result of travel restrictions and other measures coming into force to slow the spread of the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic. There was also a lot of gas in store as the feared winter gas war between Russia and Ukraine, against which injections had been very high last summer, failed to materialise. Gazprom has also ceded some market share this year to new suppliers of LNG, notably from the US. However, Russian revenues held up, despite the drop in volume, as the average unit price was actually a little higher. – NGW |