German coal exit sparks opportunity for gas [NGW Magazine]

Germany's federal commission for growth, structural change and employment in January confirmed a plan to phase out all remaining coal-fired power generation over the next 20 years.

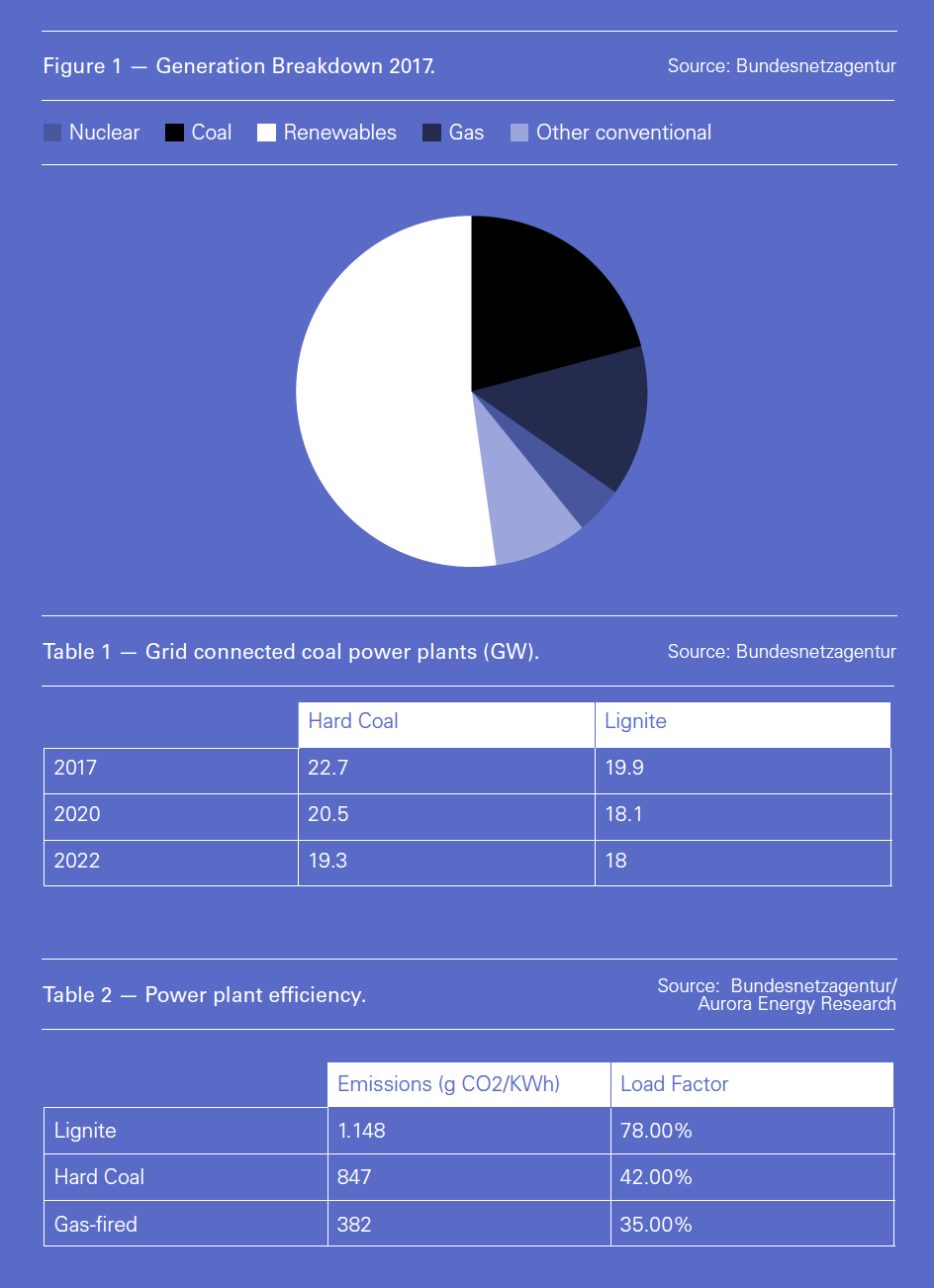

Coal, once the backbone of the German energy market, has been in steady decline over recent decades and accounts for just over a fifth of total power production, with renewable energy now dominant in the generation mix – see figure 1. But this plan will see it removed entirely from the energy mix by 2038, which raises the question: what will replace it?

The exit from coal is a key part of Germany’s plans to cut its carbon emissions in line with the commitments it made at the 2015 Paris climate summit to limit global warming to well below 2 °C. Between 1990 and 2017, emissions from the energy sector fell by 27% according to a report published in January by the commission.

A large part of this is down to efforts to use less lignite, a soft brown coal that has lower energy value and more impurities compared with hard coal like anthracite. As a domestic fuel source it is relatively cheap, compared with imported gas, and as many lignite power plants are near the end of the economic lifespans, capital costs were written off years ago, meaning that margins are only impacted by operating costs. Lignite use was especially concentrated in the former East Germany and since reunification it has been in steady decline, largely on environmental grounds.

“Emissions from the use of lignite in energy have fallen from 237mn metric tons of CO2 in 1990 to 155mn mt in 2017,” the commission's report states. The role of lignite and coal-fired generation is set to continue declining over coming years but there are calls for lignite to be phased out more quickly – see table

Slashing Carbon Emissions

Germany's Climate Protection Plan 2050, which was enacted in 2016, sets a target of carbon neutrality by 2050. There are milestones on the way – cutting emissions by 40% compared with 1990 by 2020, 55% by 2030, and 80-95% by 2050. The 2030 target incorporates EU-mandated sector level sub-targets including an energy sector target to cut emissions by over 61% from 1990 levels.

Emissions fell sharply between 1990 and 2010. But since the rapid clean-up of dirty industry, especially in the east, efforts have now stagnated with just small variances from year to year. A further factor is the decline in low-carbon nuclear power. Germany's retreat from nuclear has accelerated in the years following the 2011 Fukishima disaster in Japan. Nuclear now accounts for less than 5% of all power generation and is set to reach zero in 2022, when the last nuclear reactors close

To stand a chance of meeting the 2030 goal and subsequent targets, the commission warns that more needs to be done, especially on coal. Total emissions from coal-fired plant (lignite and hard coal) stood at 256mn mt of CO2 in 2016, according to the commission's report. And coal-fired plants now account for 70% of total energy sector emissions.

The report projects that emissions from gas-fired power plants will start rising from 2030, with back-up gas generation needed to maintain supply security against a backdrop of increased intermittent renewables. An expansion of combined heat and power for industrial and municipal users will also drive more natural gas use in generation alongside renewables like biomass and biogas.

Closures and compensation

Questions remain on how fast the exit from coal will go and whether the coal industry will be compensated for the move.

The commission has proposed compensation could run in the order of several billions of euros. But that compensation is not strictly necessary, according to the latest advice from the scientific advisory committee of the Bundestag, Germany’s lower house of parliament.

The parliament's legal service said in late January that as long as the decommissioning of coal and lignite-fired plants was conducted in a “legally ordered” way, compensation to plant operators and lignite companies RWE, Leag and Mibrag could be entirely voluntary. They would only be required in cases of unreasonable economic burdens placed on plant operators – and there is no suggestion of such burdens in the original report published by the commission.

But the commission is keen to reach a consensual agreement with operators to manage the exit and believes that this can be achieved as current coal-fired plants either reach the end of their technical lifespans or burn through the carbon allowances awarded to them under the European Emissions Trading System. Otherwise plants could close prematurely, especially if they face high carbon prices, and that could have an impact on security of supply.

As things stand, the report projects coal-fired generation capacity of between 14 and 21 GW will still be operating in 2030 which means there must be additional efforts to cut emissions.

A greater role for gas

But environmental campaigners and the gas industry advocate a swifter exit from coal, especially lignite, with gas filling the gap.

“Without additional measures, it's clear that the goal to cut emissions by 55% by 2030 will not be achieved,” warns gas industry group Zukunft Erdgas (ZE) whose members include major gas companies like Uniper and Wintershall. In particular, total withdrawal of nuclear power means there is more pressure to cut emissions.

ZE points to a study it commissioned from UK-based Aurora Energy. It projects that existing and planned gas projects could plug the gap left by remaining nuclear closures (9 GW) and by retiring 5-9 GW of lignite power. The group says Germany should aim for 9 GW or higher or it will miss its target to cut emissions by 40% from 1990 levels until 2023 – missing the target by three years.

The industry lobby calls for greater use of existing high efficiency gas-fired plant to facilitate early withdrawal of 9 GW of lignite-fired generation by 2023.

Around 30 GW of gas-fired plant is already available, most of it in the form of high-efficiency combined cycle gas turbine (CCGT) plants, many of which also use combined heat and power technology to produce heat alongside electricity, making them even more efficient.

But the study from Aurora energy concludes that the current use averages just 35%, and in some months this has fallen below 10%. Some existing gas-fired plants face closure unless they are used more. This is despite the fact that CCGTs have much greater efficiency and lower-carbon footprints (see table 2).

“Germany’s energy system therefore has untapped, efficient and low carbon power plants, but experts warn that without political will [to use more] in coming years, around a fifth of this capacity could be taken offline on economic grounds,” ZE warns.

It adds that a further 2 GW of gas-fired capacity could be online by 2023 owing to the evolution of the energy mix, and that using gas-fired plant without combined heat and power should rise to around 45% versus 28% at present.

ZE projects that a partial withdrawal from lignite generation, and a switch to gas by 2023 would have little impact on power prices, despite the fact that domestic lignite is cheaper than imported gas. The carbon content of lignite means that higher emissions permit costs need to be factored in.

The study it commissioned projects baseload power prices will be around €46/MWh ($52/MWh) on average in 2023, compared with an average of €43/MWh for day-ahead baseload in 2018, with the increase due to the exit from nuclear. It estimates the price impact of removing 9 GW of lignite-generation from the grid would take the price up to €50/MWh.

“Such a price change would be in the order of the fluctuations seen on a daily basis,” it says.

A switch from lignite to gas would also have a limited impact on security of supply, even though imported gas displaces domestic coal. This is because it would help remove a bottleneck on the power grid between the north and south. Lignite generation is concentrated in the north, with gas-fired generation in the south, so a switch would address regional imbalances, ZE says.

In terms of gas use, that switch would require 50-70 TWh of additional gas - up 8% by 2023. New LNG terminals and pipelines, along with greater integration of the EU gas grid would be able to accommodate that increase. And gas could play an even greater role in the longer term, but that would depend on how the overall energy mix evolves - including a push for much greater energy efficiency, renewable heat potentially displacing some gas in heating, and how electrical storage for renewables evolves.