Greece to expand gas hub role despite predicting sharp fall in its own demand [Global Gas Perspectives]

Greece’s revised National Energy and Climate Plan (NCEP), released in late August for consultation, forecasts a 70% decline in natural gas demand by 2050 versus the level in 2022, as renewables rise to dominate the country’s power system. This in itself is not particularly surprising, given many other European countries also predict a substantial drop in the fuel’s consumption over the decades to come. Germany, for example, expects its natural gas demand to fall by over two-thirds by 2040 and 95% by mid-century, using 2021 as a baseline.

What is more interesting is that even though Greece’s plan projects that gas demand will wane over the coming years, it also advocates for the further expansion of the country’s gas infrastructure, as Athens pursues its goal of becoming a regional hub for the fuel. Not only this, it also calls for Greece to develop its own potential gas resources so that the country might even become a net exporter, and recognises that roughly the same amount of gas-fired power capacity will be needed in 2050 as there is today, to support intermittent renewables.

Renewables displace gas

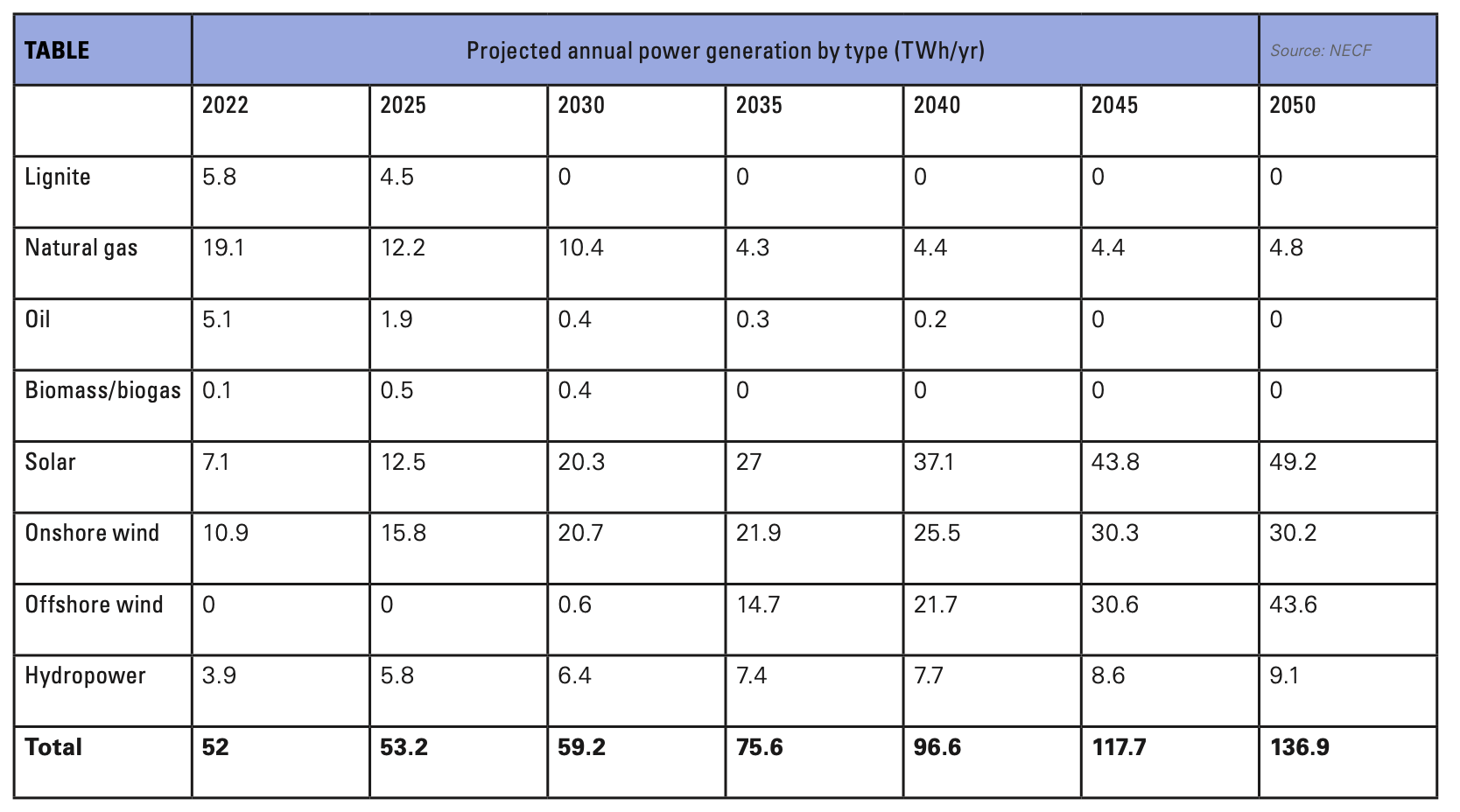

The new NECP assumes that overall gas demand will fall from 51.2 TWh in 2022 to 44.1 TWh in 2030 and to only 16.2 TWh by 2050. The largest share of gas use is in the power sector, where consumption is forecast to drop from 19.1 TWh in 2022 to 10.4 TWh in 2030 and 4.8 TWh in 2050, owing to a substantial growth in renewables. Its share will shrink from 37% in 2022 to only 3.5% by mid-century.

Greece will be producing over 80% of electricity from renewables by 2030, versus 42% in 2022, and this will rise to close to 100% by 2050, according to the plan. The main two drivers of this growth will be a sevenfold increase in solar power generation to 49.2 TWh by 2050, and a boom in offshore wind development post-2030, which should see wind farms contributing 43.6 TWh by mid-century. Onshore wind will nearly triple to 30.2 TWh, while hydro will more than double to 9.1 TWh.

Growing renewables will enable Greece to switch from being a net importer of power to a net exporter by 2035, according to the plan, thanks to a surplus of 3.7 TWh.

Lignite coal, having contributed 5.1 TWh of power or 11% of the total in 2022, will disappear from the grid by the end of this decade, in line with Greece’s 2022 commitment to phase out coal by 2028. Oil, which accounted for nearly 10% of electricity, will likewise disappear by 2045.

But gas-fired capacity is here to stay

Yet these are only projections of future power production and not capacity. Gas-fired power capacity will in fact rise from 6.3 GW in 2022 to 7.9 GW in 2030, supporting the uptake of renewables during the phase-out of coal. It will then drop to 6.4 GW by 2050 – slightly higher than the current level. Indeed, the NECF recognises that gas-fired stations will be “critical to ensure, in all cases, the stability and security of supply of the electricity system throughout the energy transition.”

These plants will need to benefit from a national compensation mechanism so that they have a financial incentive to stay active even when high renewable output floods the system. This is especially true as the use of large-scale batteries to help stabilise system is expected to take off between 2030 and 2040. Notably some oil-fired stations will also have to be kept in cold reserve, according to the plan, to ensure stable power supply to some of Greece’s islands.

Industrial gas demand will see a steep decline over the coming decades, from 6.6 TWh in 2022 to 4.9 TWh in 2030, 1.4 TWh in 2040 and 0.9 TWh in 2050. Residential/commercial demand will likewise drop from 1.3 TWh in 2022 to 1.2 TWh in 2030, 0.2 TWh in 2040 and 0.2 TWh in 2050. One key driver here will be electrification, displacing the role of gas in heating through the use of heat pumps. Greece plans to ban the sale of new oil and gas boilers by 2025. Increased EU requirements on energy efficiency in building are another factor, along with the inclusion of emissions from buildings in the bloc’s emissions trading system (ETS). The increased production of biomethane will also play a role.

Greece’s planned energy transition is a coal-to-gas-to-renewables transition and makes sense, Thierry Bros, energy expert and professor at Sciences Po Paris, tells NGW. However, he notes that not all countries can achieve such a pathway, as not all benefit from Greece’s unique amount of sun and wind resources. By embracing natural gas, Greece has already reduced coal power faster than any other country in the world, reducing its share in the power mix from 51% in 2014 to 10% in 2022.

Forecasting such a steep decline in gas is “shocking,” Matthew Bryza, managing director of Straife, tells NGW, pointing to how significantly Greece has expanded its gas consumption since the 1990s. “My money is on natural gas being used significantly for at least 30 more years – it's energy dense, it’s inexpensive and it’s so much cleaner than coal.”

Hub aspirations

Greece achieved this transition in no small part thanks to access to cheap Russian pipeline gas, which accounted for over half of its gas imports in 2021. It still receives this gas, in spite of Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine. But it has also focused significantly on expanding its own gas infrastructure in recent years.

This October, Greece is set to launch the 5.5bn m3/year Alexandroupolis LNG import terminal, joining the existing 7bn m3/yr Revithoussa facility. It also benefits from the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) that flows gas from Azerbaijan into its territory, with the Greek government estimating the country would take 1.2bn m3 of this gas this year.

Together the capacity of these projects far surpasses Greece’s gas consumption, which came to 6.4bn m3 in 2023. Greece is already a hub for gas trade in the region, and wants to expand that role in the years to come.

The NECP lists seven projects as having “national, regional and international interest,” such as the 2.5bn m3/yr Dioriga floating storage and regasification unit (FSRU) and the plan to double TAP’s capacity to 20bn m3/yr, as well as the expansion of the Interconnector Greece-Bulgaria pipeline to 5bn m3/yr, which pipes Azeri gas and regasified LNG to Bulgaria.

If all these projects are implemented, NECP notes that Greece’s transmission capacity would grow from 3.1bn m3/yr at present to 8.5bn m3/yr by 2026. However, the plans could be derailed “if the declared intention to fully decouple the EU from Russian gas is not implemented and if regional needs continue to be met mainly by Russian gas channeled through Turkey.”

In other words, Greece is counting on Brussels following through on its commitment to eliminate Russian gas imports by 2027. Russia piped 25.1bn m3 of gas to Europe in 2023, mostly to countries in its central and southeast regions which could benefit from volumes transited via Greece. Some 14.7bn m3 flows through Ukraine and could be halted at the end of this year as Kyiv and Moscow are expected not to renew their transit contract, although options are being considered to continue flow while limiting direct dealings between Ukraine and Russia. Further ahead, Hungary and Slovakia have signalled they will continue gas trade with Russia, and both have contracts that extend beyond the 2027 deadline.

Domestic potential

Lastly, NECP stresses the need for Greece to develop its own gas resources, assessed at 680bn m3 in potential and probable reserves. The government has so far awarded nine onshore and offshore licences, and named these as national priority projects in April 2022. The plan states the wells should be drilled in the next two years, and if viable discoveries are made and final investment decisions (FIDs) taken, domestic gas production could come on stream before the end of the decade.

This aspect of NECP is of course highly speculative, as it is yet to be known how much gas Greece has and how much it could actually extract. But it is indicative of a plan that is far from anti-gas, despite its bearish outlook for domestic demand. And if gas demand proves more resilient than predicted in the years to come, Greece will have ensured its future energy security through ample and diverse access to imports and, potentially, domestic supply.