Groping towards the light [NGW Magazine]

The International Energy Agency’s World Energy Outlook 2020 (WEO)could be summarised in a handful of words: “Clarity sought in the Covid-19 chaos.”

Executive director Fatih Birol enumerated the challenges in his introduction to WEO: “This has been an extraordinarily turbulent year for the global energy system… The crisis is still unfolding today – and its consequences for the world’s energy future remain highly uncertain.... We are entering a critical decade for accelerating clean energy transitions and putting emissions into structural decline…. How the world rises to these challenges will define our energy future and determine the success or failure of efforts to tackle climate change….This is the moment for ambitious action.” Strong words but appropriate to the extraordinary challenges posed by the Covid-19 pandemic on the outlook for global energy. Predicting the future of energy has become that much harder.

As the IEA points out, the Covid-19 pandemic has caused more disruption to the energy sector than any other event in peace-time history, leaving impacts that will be felt for years to come. As a result of the uncertainties over the duration of the pandemic, its economic and social impacts and policy responses, there is no single story-line about the future.

For this reason the IEA has focused on the coming decade and considered a number of scenarios to cover a wide range of possible energy futures:

- Stated Policies Scenario (Steps): This is based on all the policy intentions and targets announced to date, provided they are backed up by detailed measures for their realisation. It assumes that Covid-19 is gradually brought under control in 2021 and the global economy returns to pre-crisis levels the same year.

- Delayed Recovery Scenario (DRS): Based on the same policy assumptions as Steps, but a prolonged pandemic causes lasting economic damage. The global economy does not recover the lost ground until 2023, and the pandemic ushers in a decade of the lowest rate of energy demand growth in almost a century.

- Sustainable Development Scenario (SDS): In this, a surge in clean energy policies and investment puts the energy system on track to achieve sustainable energy objectives in full, including the Paris Agreement, energy access and air quality goals, but with net zero only by 2070. The assumptions on public health and the economy are the same as in the Steps.

- Net-Zero Emissions by 2050 (NZE 2050): This extends the SDS analysis. NZE 2050 includes the first detailed IEA modelling of what would be needed in the next ten years to put global carbon emissions on track for net zero by 2050.

Without further policy change Steps – or DRS if the pandemic is prolonged – is likeliest to happen. So it is a warning of the consequences of global inaction.

The IEA states that energy demand in 2020 is set to be down year-on-year by around 5%. Oil demand is anticipated to decline by 8%, gas by 4% and coal by 7%, while renewables will see a small growth. Energy investment will be down by 18%.

Global energy demand rebounds to its pre-crisis level in early 2023 in Steps, but this is delayed until 2025 as in DRS. Before the crisis, energy demand was projected to grow by 12% between 2019 and 2030 but is now expected to be 9% in Steps, and only 4% in DRS, driven by emerging economies such as India.

Birol said low economic growth is not a solution to climate change. “It is a strategy that would only serve to further impoverish the world’s most vulnerable populations,” he said.

What is needed is a structural transformation of the energy sector that will require massive investment in more efficient and cleaner capital stock, as well as “the way we produce and consume energy.” Birol warned that “no sector will be unaffected by clean energy transitions.”

Renewables grow fast

WEO’s key findings are:

- Renewables grow rapidly in all scenarios, with solar becoming the new king of electricity, being consistently cheaper than new coal- or gas-fired power plants in most countries. In Steps, renewables meet 80% of the growth in global electricity demand out to 2030, but electricity grids could be the weak link, with implications for the reliability and security of supply.

- Coal demand does not return to pre-crisis levels in Steps and its share in the 2040 energy mix falls below a fifth. Coal phase-out policies, the rise of renewables and competition from natural gas are its main obstacles to growth.

- The era of growth in global oil demand comes to an end within ten years, flattening out in the 2030s in Steps, but the shape of the economic recovery is unknown. Without bigger policy shifts, oil demand cannot be lowered much.

- Natural gas does the best of the fossil fuels, but with a wide range of outcomes depending on policy. In Steps, a 30% rise in global natural gas demand by 2040 is concentrated in south and east Asia, underpinned by low prices. But the prospects for the record amount of new LNG export facilities approved in 2019 will be mixed.

- Methane emissions along gas supply chains remain a crucial uncertainty, but greater transparency seems to be on the way. For example, the Oil & Gas Climate Initiative and two other organisations have formed a group to monitor and reduce methane leaks (https://www.naturalgasworld.com/new-industry-initiative-to-measure-methane-leaks-82561). There is also the European Commission’s methane strategy, which will have implications for the environmental credentials of different sources of gas as it evolves.

- Oil and gas producers face major dilemmas. Lower prices and demand forecasts have this year cut around one-quarter off the value of future oil and gas production, leading to impairments across the sector.

- Electricity takes an ever-greater role in overall energy consumption, with rising output from renewables.

- With global emissions set to bounce back after Covid-19, the world is still a long way from a sustainable recovery. But a big increase in clean energy investment would imply economic recovery through job creation as well as reduce emissions of carbon and, in the very short term, the far more harmful particulates.

- Avoiding new emissions is not enough. If nothing is done about emissions from existing infrastructure, climate goals will be out of reach. New analysis shows that if today’s energy infrastructure continues to operate as it has in the past, it would lock in a temperature rise of 1.65 °C.

- The power sector can take the lead, but a wide range of strategies and technologies are required to tackle emissions across all parts of the energy sector. With annual additions of solar PV almost tripling from today’s levels, emissions from the power sector drop by more than 40% by 2030 in SDS.

- Governments must guide the actions of others to avoid energy supply becoming either unreliable or unaffordable.

Birol highlights the challenges ahead: “There’s a lot of work to be done in the energy sector. But the actions of the energy sector alone will not be enough.” Governments have “the capacity and the responsibility to take decisive actions to accelerate clean energy transitions and put the world on a path to reaching our climate goals, including net-zero emissions.” Policy makers must act. “We are far from reaching our climate goals with the existing policies around the world.”

Total primary energy

The IEA says that how total primary energy evolves in the short and long-term depends on the impact of Covid-19 and the prospects for accelerated energy transitions.

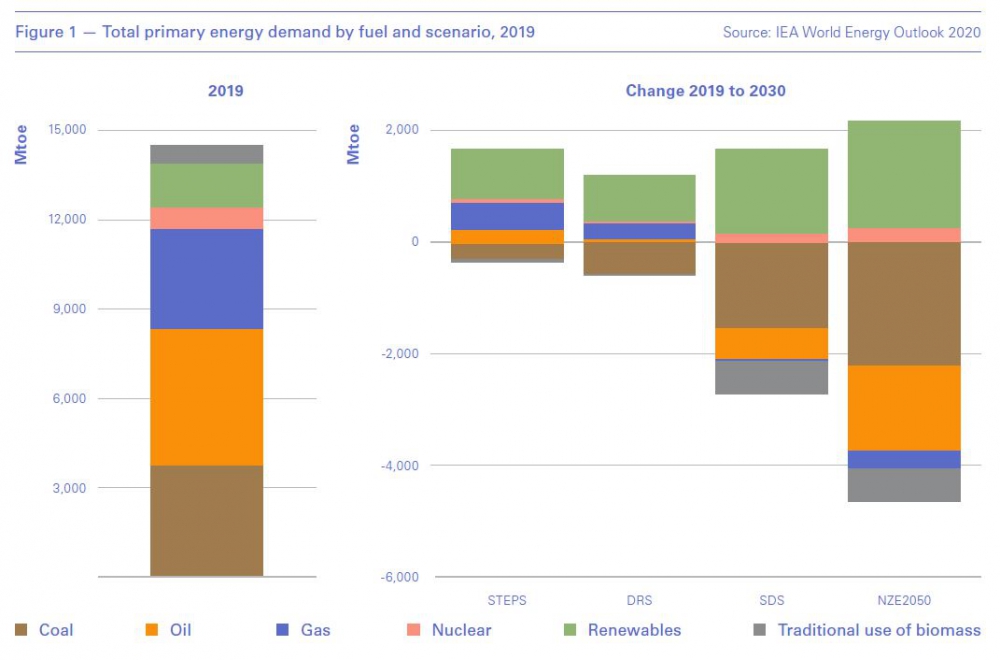

Over the next ten years these will be affected by major uncertainties, in particular relating to the duration and severity of the pandemic. This is demonstrated in Figure 1.

In both Steps and DRS total primary energy demand grows this decade, while in SDS and NZE 2050 it actually declines – by about 7% and 17% respectively.

However, the IEA is quite pessimistic about realising the pace and scale of emissions reductions required in NZE 2050. The scale of the transformation of the energy sector is colossal and the deployment of clean energy technologies and wide-ranging behavioural changes – in all sectors and in all countries simultaneously – is a major challenge, especially in transport and in Asia and Africa.

The IEA also states that “the pandemic has intensified the uncertainties facing the oil and gas industry. The timing and extent of a rebound in investment from the one-third decline seen in 2020 is unclear, given the significant overhang of supply capacity in oil and gas markets, and uncertainties over the outlook for US shale and for global demand.”

It adds that “pressure is meanwhile increasing on many parts of the industry to clarify the implications of energy transitions for their operations and business models, and to explain the contributions that they can make to reducing emissions.”

Adopting energy-efficiency measures means that most major regions are set to save more energy on an annual basis in the 2019-30 period than they did in the previous decade. In Steps, energy intensity improvements gain on average about 2%/yr this decade. But these depend heavily on the economic recovery.

Renewables

According to the IEA power generation from renewables is the only major source of energy that has continued to grow in 2020, by 1%, and this resilience sets the tone for this decade and beyond.

Renewables are expected to grow significantly, thanks to the rapid expansion of wind and solar PV, while renewables in end-use sectors, heat and transport, will continue to be dominated by biofuels (Figure 2).

Over the coming decade, wind and solar grow by 10% year-on-year. Solar power is the "new king", with the IEA calling it the cheapest form of electricity in history.

Natural gas

Natural gas demand has been more resilient to the immediate impact from the Covid-19 crisis than coal and oil, but it is still expected to decline 3% in 2020.

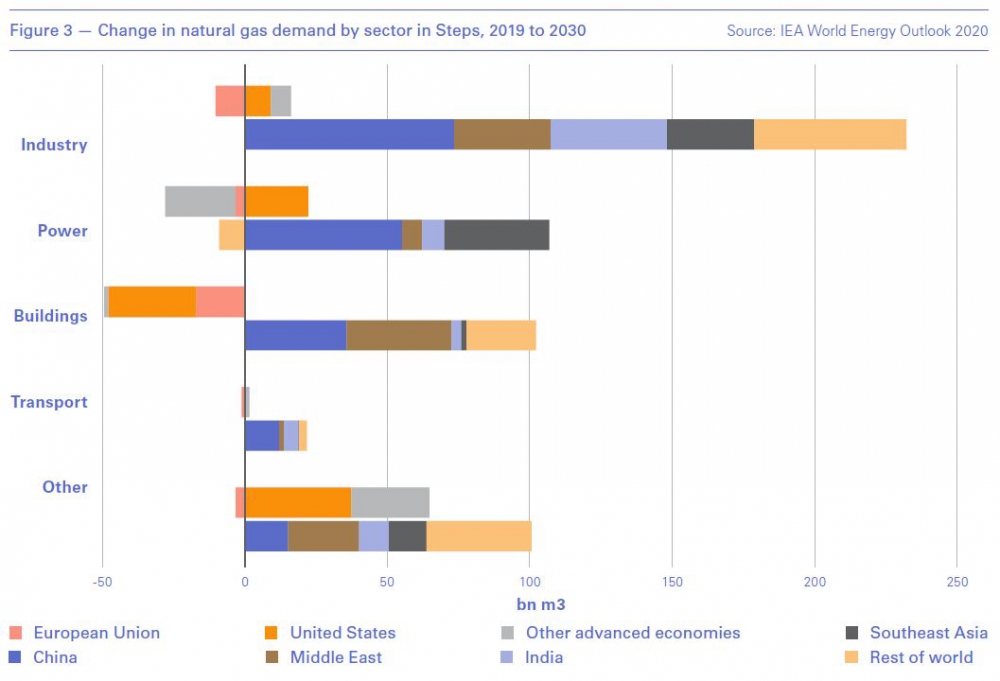

The majority of natural gas demand growth over the next decade is expected to occur outside of advanced economies, especially in China, India, southeast Asia and the Middle East, spurred by an oversupplied global gas market and low prices.

However, the IEA warns that gas faces significant uncertainty. Despite a lower price outlook, growth relies heavily on policy support – for example, clean air – and on significant investment in new gas infrastructure. And in more established markets, gas faces competition from ever cheaper renewables and environmental pressures.

Overall gas demand is expected to recover quickly, reaching 4.6 trillion m³ by the end of the decade, nearly 15% higher in 2030 than in 2019. Emerging economies lead the growth, with demand in more mature markets remaining broadly static (Figure 3). China and India account for around 45% of total gas demand growth over the next decade.

As Jonathan Stern, distinguished research fellow at Oxford Institute of Energy Studies, pointed out at the Energy Intelligence Forum (EIF), in Europe “the gas-is-better-than-coal narrative has run its course as it wasn't really ever embraced by politicians or environmentalists.” But it still works outside Europe. And within parts of Europe it might still succeed, on price and pragmatic grounds, as Germany dismantles its nuclear plants and then its coal.

Global natural gas markets were in search of balance well before Covid-19. As the year began, there was already a significant overhang of supply capacity accruing. They remain amply supplied, and the timing of any rebalancing is highly uncertain: with nearly 200bn m³ of LNG projects officially deferred since the start of 2020 and several upstream projects on ice, global gas markets face an uncertain future. Achieving a smooth balancing between LNG supply and demand over the coming years is by no means a given.

The IEA warned that "higher cost development projects…look increasingly difficult to justify," particularly in Europe, the North Sea, South America and the eastern Mediterranean. With Qatar announcing at EIF that it plans to increase LNG production beyond 126mn metric tons/yr, the pressure on planning new projects at these regions and elsewhere will increase further.

Oil and coal

In Steps, global oil demand returns to pre-crisis levels by around 2023. Without serious policy changes demand would then rise on average by 0.7mn b/d each year until 2030 (Figure 4).

Beyond 2030, global oil demand reaches a plateau, with annual growth slowing to 0.1mn b/d. However, there is a high degree of uncertainty around the shape of the economic recovery, which could turn out to be slower than assumed in Steps.

This growth is driven by increasing demand in Asia. India remains the largest source of growth in oil this coming decade, mainly in transport. In China oil demand peaks by 2030, but still remains a key contributor to global oil demand.

Oil demand in advanced economies recovers in the near term, but never returns to pre-crisis levels.

Coal bore the brunt of the decline in electricity demand related to the pandemic, with demand expected to fall by 7% in 2020. The IEA expects that small increases from 2020 levels are likely as economies around the world recover from the pandemic, driven by China and India, but coal demand is unlikely to pass 2019 levels again.

Electricity

The electricity sector will play a key role in supporting economic recovery, and an increasingly important long-term role in providing the energy that the world needs. Over time it looks set to evolve into a system with lower carbon emissions, a stronger infrastructure base and enhanced flexibility.

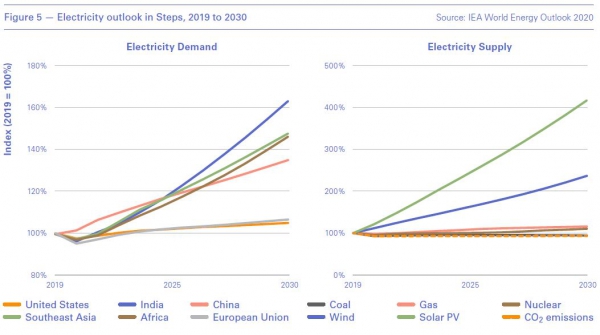

In Steps, global electricity demand recovers and surpasses pre-Covid-19 levels in 2021. Electricity demand growth is fastest in India to 2030, after which growth is most pronounced in southeast Asia and Africa (Figure 5). Electricity demand growth globally outpaces all other fuels, meeting 21% of global final energy consumption by 2030.

Renewable sources of electricity have been resilient during the Covid-19 crisis and are set for strong growth, rising by two-thirds from 2020 to 2030 in the Steps. Renewables meet 80% of global electricity demand growth during the next decade and overtake coal by 2025 as the primary means of producing electricity. By 2030, hydro, wind, solar PV, bioenergy, geothermal, concentrating solar and marine power between them provide nearly 40% of electricity supply.

Solar PV becomes the new king of electricity supply and looks set for massive expansion. From 2020 to 2030, solar PV grows by an average of 13%/yr, meeting almost one-third of electricity demand growth over the period.

Coal’s share of global electricity generation falls to 28% in 2030 in Steps, down from 37% in 2019 and 35% in 2020. However, new additions are expected up to 2025.

Emissions

The IEA states that the emissions trajectory remains far from the immediate peak and decline in emissions (Figure 6) that is needed to meet climate goals, including the Paris Agreement. Provided decisive policy measures are taken, “there are reasons for optimism about the future. But there should be no illusions about where we are today: the world is still well off-track to address climate change and meet sustainable development goals.”

Emissions are reduced relative to pre-crisis levels in each scenario, but only SDS leads to their long-term structural decline.

But the IEA warned in its Energy Technology Perspectives (ETP) report published in September that about 40% of cumulative emissions reductions rely on commercially non-existent technology.

These new technologies – particularly hydrogen production, batteries and carbon capture use and storage – have to be fast-tracked.

Challenges

In advanced economies, and particularly in Europe, environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors are gaining traction.

This, and the low number of countries outside Europe taking clean energy seriously, make DRS the likeliest of the four scenarios.

DRS depicts a world where high unemployment erodes human capital and bankruptcies and structural economic changes render some physical capital unproductive. Consumer behaviour is radically altered and with it, company strategies. By 2030, the global economy is nearly 10% smaller than in the Steps,” slowing down energy demand growth.

The extent of these uncertainties becomes clear when one considers the great spread in projections made regarding future oil demand by a number of reputable international organisations, such as BP, DNV-GL, EIA and IEA. Opec projects oil demand to carry on increasing to over 109mn b/d by 2040, as does Steps, while BP’s net-zero scenario expects it to carry on declining down to just under 60mn b/d over the same period, as does IEA’s SDS, with all shades in between by the others and other scenarios.

Hydrogen can extend electricity’s reach. But according to IEA’s SDS, in order to produce the low-carbon hydrogen required to reach net-zero emissions the global capacity of electrolysers – which produce hydrogen from water and electricity – would need to expand to 3,300 GW, from 0.2 GW, consuming twice the amount of electricity China generates today.

China has already returned to growth. After a drop early in the year, by early summer China’s carbon emissions rebounded, in line with its economic and energy consumption recovery. It imported 17.5% more oil this September than last September. Without policy change, this is indicative of what may be on way for other Asian economies.

And even though the president, Xi Jinping, said China aims to achieve peak emissions before 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060, 250 GW of new coal-fired power plants are now under development. This is more than the entire generating capacity of the US.

But with tensions between China and the US/Europe expected to continue, global energy trade and economic growth face headwinds.

Much also will depend on the outcome of the forthcoming presidential elections in the US, with Biden having made clean energy central to his future policies.

|

Opec asks crisis, what crisis? IEA’s Steps projections are quite bullish, but below Opec’s. The latter published its annual World Oil Outlook 2020 (WOO) October 14. It expects oil demand to recover and increase to 103.7mn b/d by 2025 and 107.2mn b/d by 2030. Opec forecasts oil demand rising to 109.3mn b/d by 2040 before declining, driven by demand in non-OECD countries. OECD oil demand will not return to 2019 levels, but Opec expects it to recover and peak by 2025, before it starts a longer-term decline. Road transport will continue to dominate in Opec’s view but the cartel accepts that the rising penetration of alternative vehicles will limit oil demand growth. The largest, compensating, growth will come from petrochemicals, taking about 40% of the growth between 2019 and 2045. However, Opec admits that future oil demand and supply is clouded by many uncertainties. Adoption of more stringent energy policies and faster penetration of energy-efficient technologies could impact demand by as much as 10mn b/d by 2045. Nevertheless, Opec believes that low-cost producer nations would “continue to play an all-important role in supplying oil to the world, even in a future in which oil demand no longer grows, or even declines.” After all, their whole reason for existing is to develop national oil and gas reserves. The upshot of Opec’s WOO is that the oil industry will not roll over. It will adapt. As the IEA points out, even in SDS the oil and gas industry will still require investment of about $425bn/yr to meet demand as supply declines faster than demand does. |