Henry Hub loses some sparkle [NGW Magazine]

The recent rises in US gas prices, combined with falls in crude – and so most LNG which is priced against crude – could make the economics of exporting LNG from the US rather less attractive, at least temporarily.

The recent rises in US gas prices, combined with falls in crude – and so most LNG which is priced against crude – could make the economics of exporting LNG from the US rather less attractive, at least temporarily.

With many buyers of US LNG purchasing long-term under US Henry Hub-linked prices, it will put upward pressure on costs among recipients of US imports and make alternatives cheaper.

A key element in the LNG supply outlook for the next decade is a dramatic rise in US export capacity. The US shale basins have some of the lowest-cost conditions for gas production in the world, outside parts of the Middle East and Russia, with a large volume that can be produced for less than $3.50/mn Btu. And because much of the gas is liquids-rich, it can cover production costs at lower prices still, which boosts output even if gas prices are weak.

Over the last four years, US prices have stayed at below $4/mn Btu – apart from a brief spike last winter – which has made the economics of US LNG exports very attractive. This is particularly the case in Asia, where prices have been much higher. But North American gas prices have not always been so subdued. Looking back 10 to 20 years, there have been many periods when Asian LNG prices were below US gas prices plus liquefaction and freight. Cheap and plentiful shale gas means we are unlike to see the days of $15/mn Btu gas in the US again for some time, but there is always the risk of it tightening up to some extent – making US exports less competitive with crude-linked or overseas spot pricing.

Indeed, over the last few weeks, US gas prices have risen to over $4.50/mn Btu for front month Henry Hub, with Nymex futures trading hitting an all-time daily volume record of more than 1.2 million contracts early in November, coinciding with the biggest one-day price gain in eight years. The price strength reflects worries over cold winter forecasts and low US gas stocks, which now sit at 3.2 trillion cubic ft³, the lowest in more than a decade for mid-November. The futures price rises extend to March, suggesting that prices could be pressured all winter by the low stock levels and relatively low production this winter compared with previous years.

Global connection

US LNG sellers prefer to sell their gas using established US gas benchmarks, rather than based on a formula linked to oil prices – which still prevails in most of the world – partly because US LNG export projects are largely structured independently of upstream production. They must buy the gas at local prices. Therefore, most importers of US LNG will feel the impact of the higher US prices.

As US exports grow, such fluctuations in US prices are likely to have a growing influence on global LNG prices and possibly European benchmark prices, but the volumes are not yet sufficient. European prices rose significantly towards the end of summer, before easing back partly because of a flood of relatively cheap LNG in October and November as key Chinese demand eased.

Higher US gas prices since then have no doubt put some upward pressure on global LNG prices, but the effect has been limited. Alternative supplies into Europe, including from Russia’s new Yamal train, will become relatively cheaper when US prices rise, whether they are priced against crude or West European gas benchmarks.

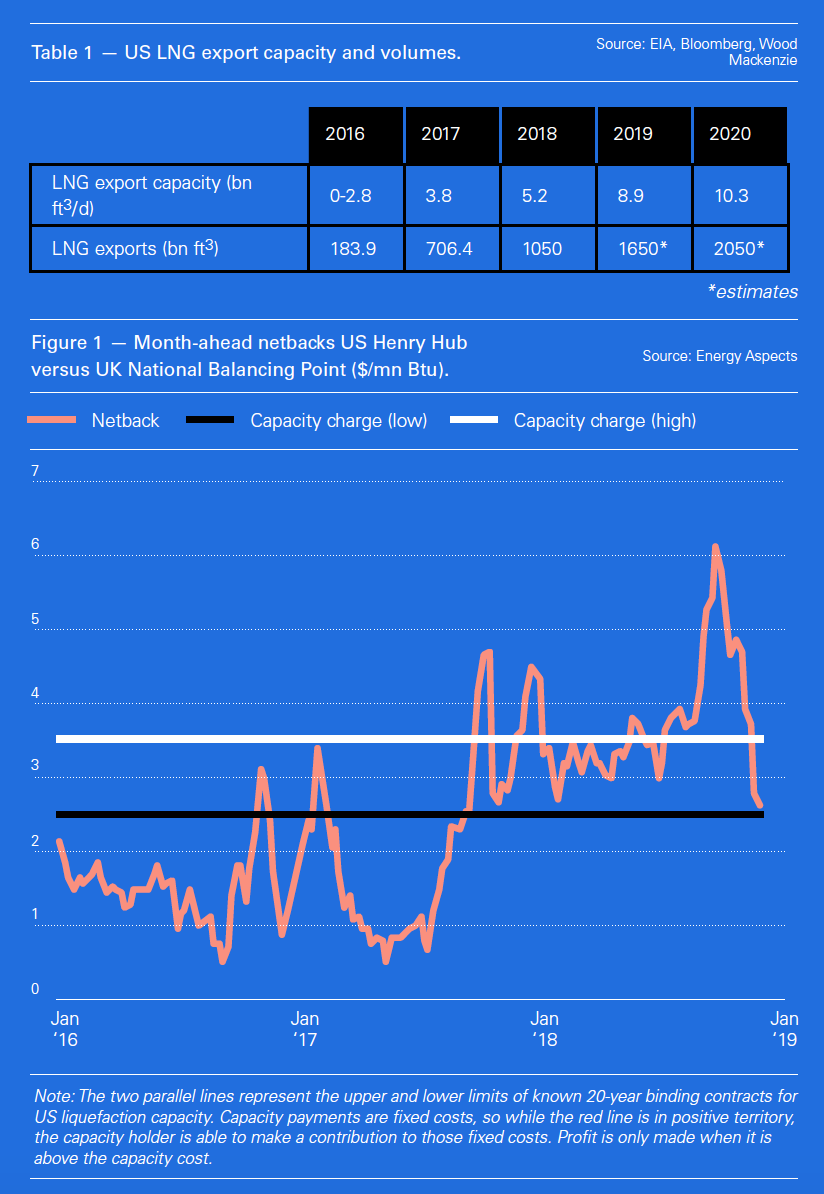

Today, operating US LNG export capacity is limited to Cheniere's Sabine Pass terminal in Louisiana and Dominion Energy's Cove Point terminal in Maryland, which shipped its first cargo earlier this year. By the end of next year, though, LNG export capacity is expected to jump to 8.9bn ft³/d as shown in the table below. All this capacity will be added in Texas and Louisiana, except for Kinder Morgan's Elba Island facility on the coast of Georgia.

Whether or not these new facilities are fully used is likely to depend on the differential between US gas prices, and those in destination markets, as well as on the volume of term sales deals.

Term influence

US export deals are normally priced with a fixed component, along with a larger element linked to the variable benchmark – which is most often Henry Hub. For example, India’s national gas supplier, Gail’s, 20-year 3.5mn mt/yr deal with Cheniere for supply to India was agreed at a price of $3/mn Btu plus 115% of the Nymex Henry Hub natural gas futures contract for the month in which the relevant cargo is scheduled.

However, this deal was concluded in 2011, when the international LNG market was tighter than more recent years, putting it at the top end of the price scale for term US LNG export sales contracts – which resulted in Gail attempting to renegotiate the price formula after international LNG spot prices weakened from 2015. Many of the deals struck during the middle of the decade have a lower fixed component or percentage link.

The recent rise in US prices towards $5/mn Btu means US LNG exports will now be costing $10-$13/mn Btu by the time it is delivered to Asian customers, which on an energy equivalent basis equates to oil prices ranging from $60 to $75/barrel. Spot prices for January delivery in North Asia are (at the time of writing, 30 November) close to the bottom end of the US-linked export price range, at about $9.80/mn Btu. The rise in US prices will also reduce buyers’ leverage with oil-linked sellers, which had been rising when US prices remained below $3/mn Btu.

European buyers have also already signed contracts for future US-based cargos at Henry Hub-linked prices. But, so far, these volumes are a fairly small part of their gas supply portfolio. Recent deals include Poland’s PGNiG, which signed a Henry Hub-linked deal with Cheniere Energy on November 8 for 0.52mn mt/yr, rising to 1.45mn mt/yr from 2023 onwards. PGNiG CEO Piotr Wozniak said Poland paid around 20-30% less for gas from the US than it did for Russian supplies. But that could change if US gas prices go higher.