For Dutch Chemical Industry, Climate is Life or Death Question [Gas Transitions]

When Martijn Broekhof went to work for the Dutch chemicals industry association VNCI last year, many of his friends were surprised. He had been working as economist for the European Climate Foundation (ECF), a philanthropic foundation that “helps Europe foster the development of a low-carbon society,” and before that for the World Economic Forum and PWC. Now he has joined industry – “the polluters”. But for him it was a logical step: “At ECF I was already building bridges between industry and the environmental movement, so when VNCI asked me help them develop their climate strategy, it seemed a great opportunity,” he told NGW.

He notes that “as an environmentalist you always have the moral high ground. But industry has to make real investments. This is where it hurts, where jobs are impacted, but also where you can make a real difference. If you are serious about the future you have to look at climate from an economic perspective, not just an environmental perspective.”

Dutch energy-intensive industry is finding itself in a particularly challenging environment at the moment, notes Broekhof. “Until recently, the Netherlands was a laggard in climate policy. But now we are moving ahead of the pack. Our industry is having to meet very concrete targets for 2030. I don’t see many other countries going that far.”

Climate Accord

This change in Dutch climate policy began in October 2017, when the four-party coalition government adopted ambitious greenhouse gas emission reduction targets: 49% by 2030 (compared with 1990), with an even higher relative target for industry (59%). For the first time, says Broekhof, the Netherlands was being more ambitious than the EU, which has a 40% reduction target for 2030.

There were various reasons behind this change of course, Broekhof explains. There was the Paris Agreement in December 2015, as well as the court case brought by environmental NGO Urgenda against the government. In June 2015, the district court of The Hague ruled that the Dutch state must do more to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in order to protect its citizens. The verdict was upheld in appeal in October 2018 and is now under appeal again. The earthquakes in the gas-producing region of Groningen also played a part in convincing the Dutch government that change was needed.

Under the new climate plan, the Netherlands aims to reduce its emissions by 49mn metric tons (mt) in 2030 compared with 2015, of which industry must contribute 14.1mn mt. Compared with current levels the reduction is even bigger, almost 20mn mt; and compared with 1990 the reduction is 41mn mt, or 59%. “That’s a very big challenge,” he says.

To implement the new policy, the government asked civil society organisations (labour unions, environmental groups, industry associations, local governments) to negotiate a “Climate Accord”, which was to indicate for each sector (electricity, industry, built environment, transport, agriculture) how its targets would be achieved. The Draft Climate Accord was published in December 2018 and will now be discussed by Dutch parliament before it is entered into law.

In the negotiations for the Climate Accord, representatives from industry managed to come up with concrete proposals together adding up to 23.6mn mt of emission reductions by 2030 – even more than the 20mn mt required, says Broekhof. That was the good news. But these projects would cost an average of €84/mt, and some as much as €200/mt of CO2, Broekhof adds. The December 2019 CO2 price in the EU Emission Trading System, is around €25/mt. So there is a big gap that needs to be covered.

Sensible CO2-price

How? That is the big question. Under the Climate Accord, the negotiating parties agreed that the industrial companies in the Netherlands would each come up with their own CO2-emission reduction plans to meet the 2030 target and “zero carbon” in 2050 and that financing would be sought under a government support scheme (called SDE-++, in Dutch jargon).

However, the Dutch government’s environment assessment agency (PBL) published an assessment of the Climate Accord, in March, which concluded that this implementation plan was too “uncertain” to ensure that the targets would be met. In response, the government announced it would instead consider imposing a “sensible CO2 price” on industry. Since then the (Leftist) opposition in parliament has been demanding that the government will make good on this promise as soon as possible.

Broekhof says the industry regrets the turn the discussion has taken. “Industry is already subject to the EU ETS, which foresees a 43% emission reduction in 2030. No other country in the world imposes a separate CO2 tax on its industry, except Singapore. The UK and Sweden have additional CO2 charges, but they have exempted their industry.”

Unfortunately, notes Broekhof, it seems that industry is regarded with increasing suspicion in the public debate in the Netherlands. “The idea was that we were going to do this together. Now many people are simply insisting that ‘industry has to deliver’. The climate debate has narrowed into a debate on a CO2 tax on industry. The risk is that this will chase industry and, more importantly, low-carbon investments out of the country, which is something the government does not want to happen either.”

Binary switch

What many people fail to realise, says Broekhof, is that achieving substantial emission reductions works very differently in industry than in electricity generation. “In electricity, you can gradually replace fossil-based generation by renewables. In industry it’s about actually changing the production processes. It’s often a binary switch.”

He points out that “energy” (tail-pipe) emissions are only part of total industrial emissions. “The majority of our emissions are non-energy related, end-of-life emissions. Over 60% of the primary energy input into the sector comes in the form of feedstock to build chemical products. These lead to product lifecyle emissions, which happen downstream, as a product is used or discarded. To get rid of those, you either need to recycle, or you need to completely change the way you make your products.”

And there is another difference between industry and electricity, notes Broekhof. “If you want to have wind turbines built offshore, you can simply put out a tender and let producers compete. Changing industrial processes doesn’t work that way. The companies have to take tasks upon themselves.”

What this means is that simply imposing a CO2 price on industry is not going to do the trick. “The stronger the ETS, the better,” says Broekhof. “But a CO2 price alone is not sufficient to make a real transition happen. It is not enough, and not certain enough, to allow industry to switch its production processes.”

With current policy, based on “counting tons”, as Broekhof puts it, the risk is that industry will merely choose the cheapest, short-term solutions. “But what we need is investment in new technologies. For example, if we are going to switch to green hydrogen we need far-reaching cooperation with the power sector, eg with Tennet, the transmission system operator, which will have to build the cables that will be needed. Or if we want the chemical industry to switch to bio-based processes, that’s a huge change, which can’t be achieved by turning a few dials. This is only feasible in the context of a national and preferably international industrial policy. That’s lacking at the moment.”

Broekhof reveals that the challenge is so urgent for the industry, that the CEO’s of the twelve biggest industrial companies in the Netherlands are currently meeting every two weeks to discuss climate policy. “This is very big for them. What choices will they make? When? For them it’s an existential question.”

|

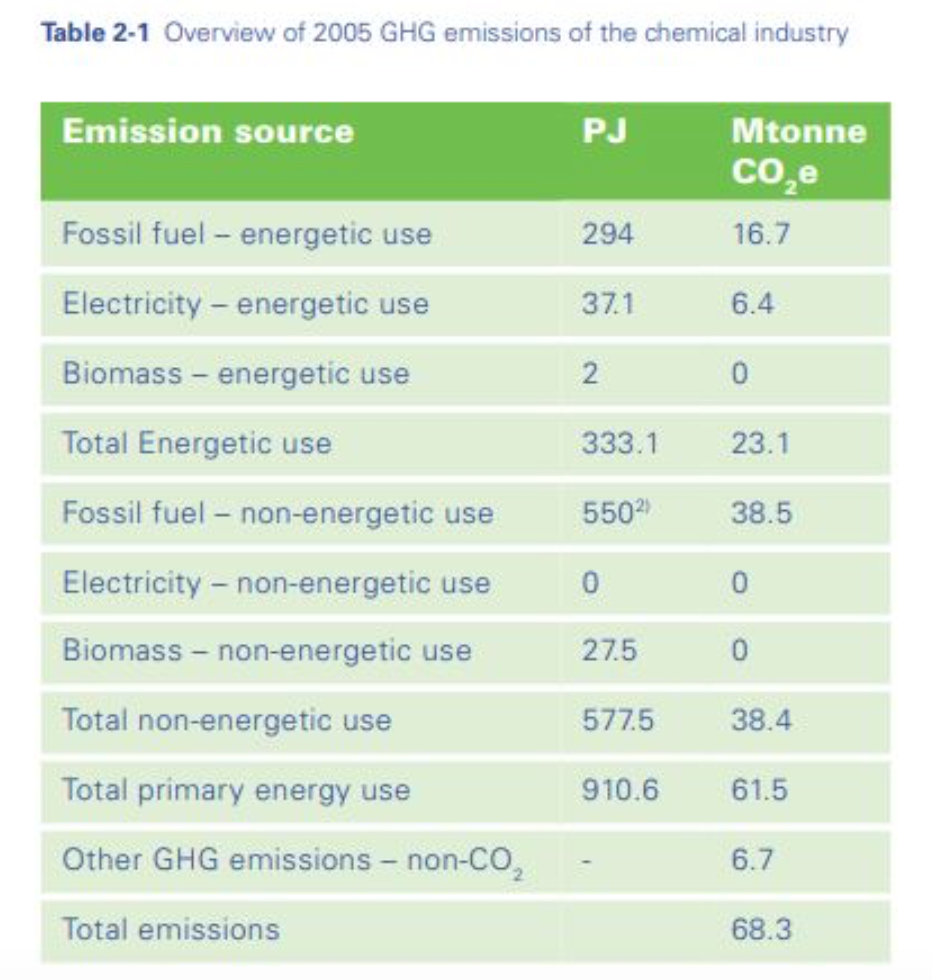

Chemical industry sees future in recycling, bio-materials, electrification, CCS In February 2018, the Dutch chemicals industry association VNCI published a roadmap, called Chemistry for Climate: Acting on the need for speed, written by consultancies Berenschot and Ecofys (Navigant), which shows how the industry could achieve 80-95% greenhouse gas emission reductions by 2050. The industry first established a baseline overview of emissions in 2005, which came out as follows: Next it identified what the emission reduction trajectory would look like for “energy” and “non-energy” emissions:

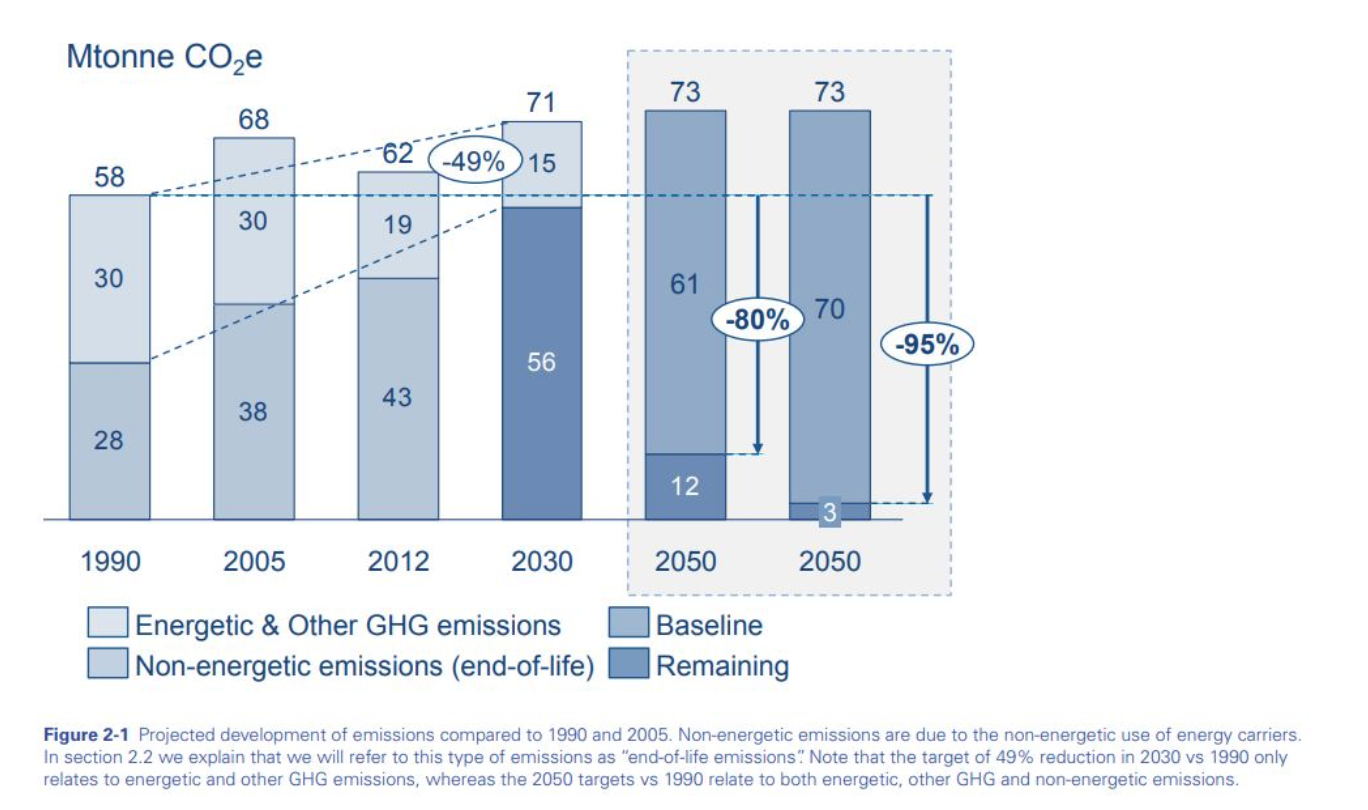

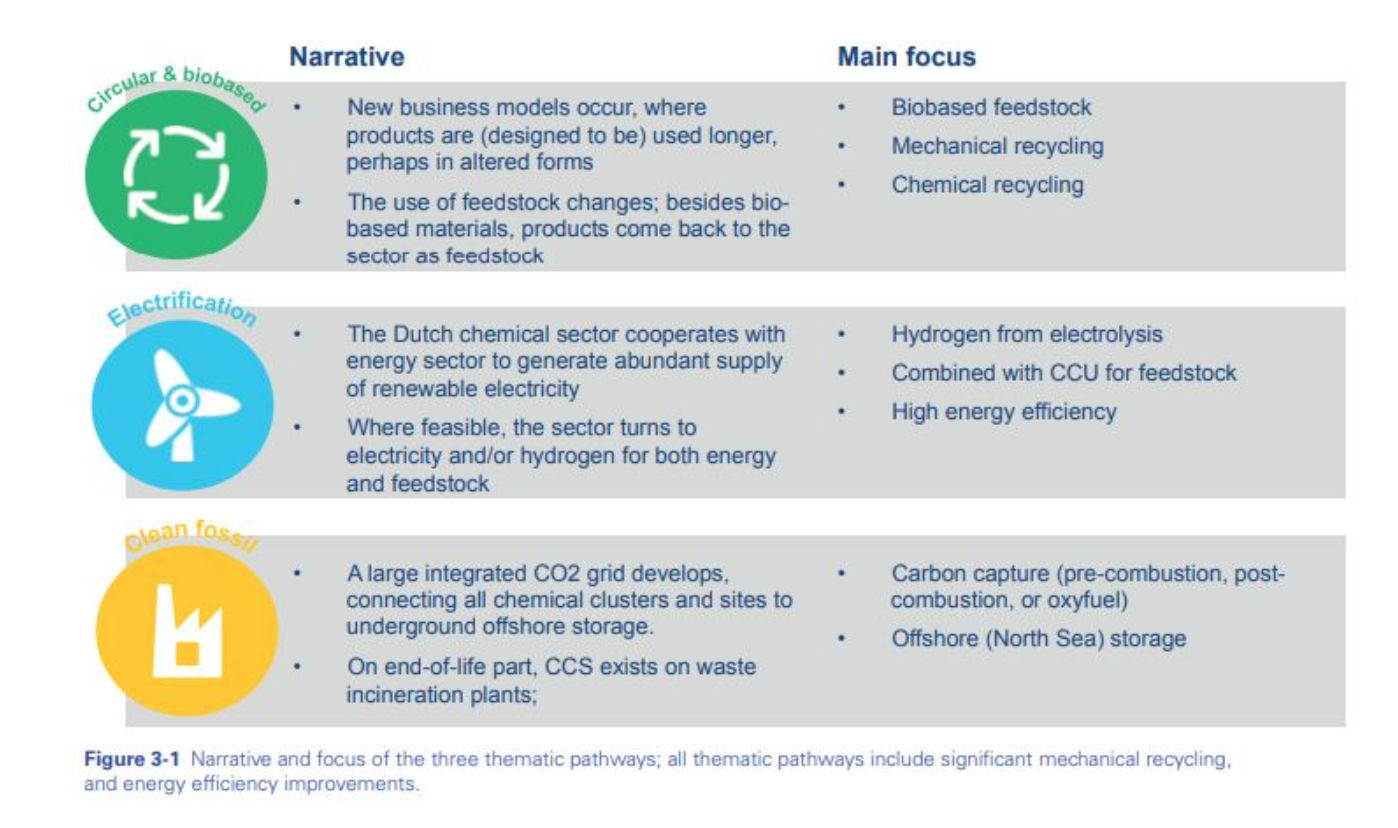

The report notes that “the 80-95% reduction target translates into 60-70mn mt CO2 reduction in absolute terms in 2050. The figure [2.1] also shows that the 49% target for reduction of energy and other GHG emissions in 2030 compared with 1990 would lead to an absolute 15mn mt emissions reduction in 2030. The remaining 56mn mt is built up of end-of-life emissions (38mn mt) and remaining energy and non-greenhouse gas emissions (18mn mt). Emissions from energy are assumed to grow by 0.43%/year.” The study subsequently explores “thematic transition pathways” based on three “narratives” which are summed up in the following chart:

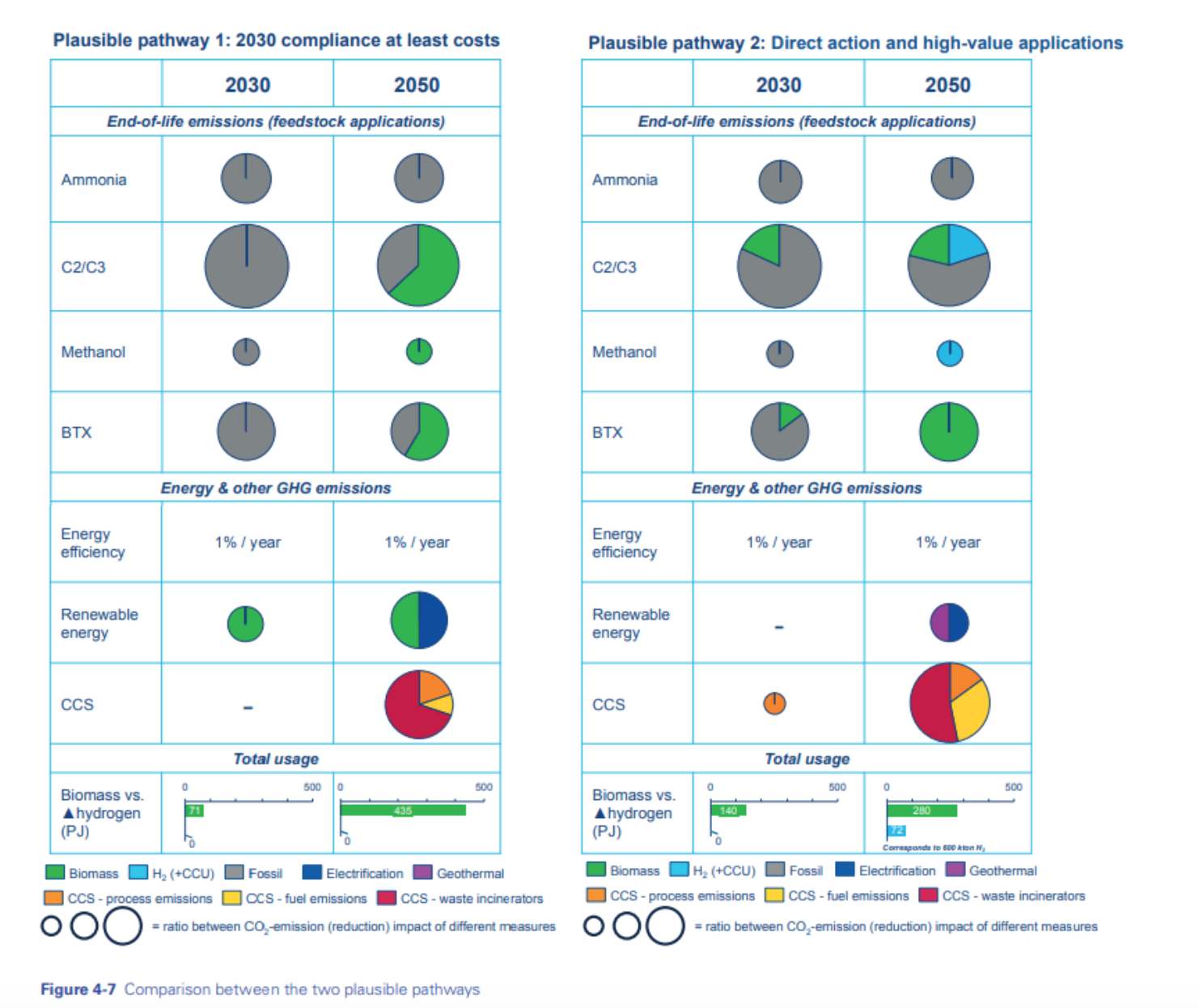

Based on these narratives, the researchers developed two “plausible combination pathways:” “2030 compliance at least costs” and “direct action and high-value applications.” The implications for the energy mix in the two pathways are shown in the following figure:

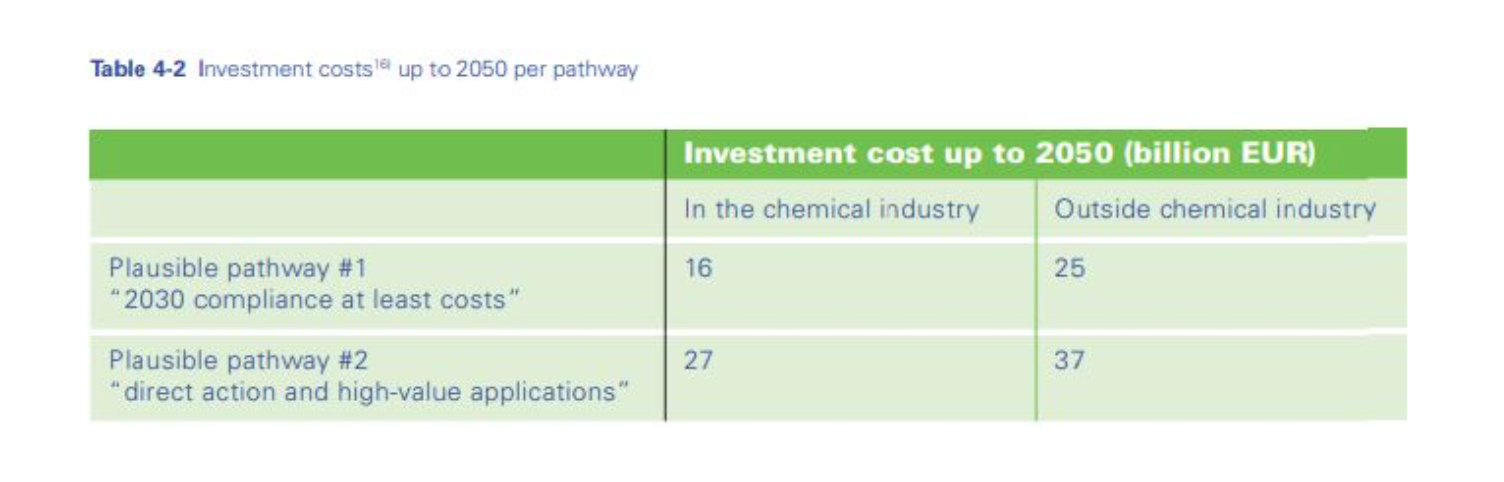

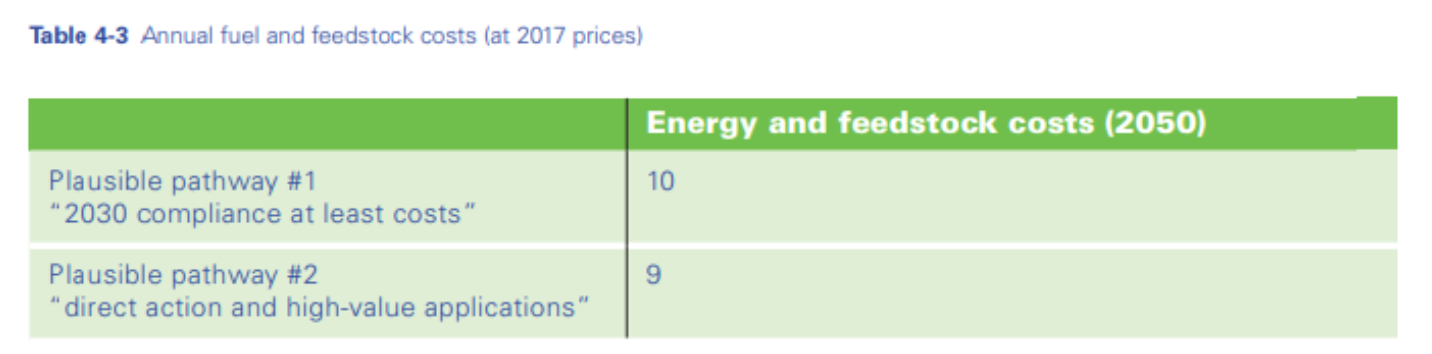

The second pathway, says Martijn Broekhof, head of Unit Climate & Energy at VNCI, is the preferred one for the industry: although it is more expensive, it is ultimately more sustainable, since it tackles the most difficult parts of the transition at an earlier stage. Note that carbon capture and storage is an important part of the mix in both pathways and “fossil” energy – much of which is natural gas – will also remain important. The costs of the two pathways are summarised in these two tables:

Note that energy and feedstock costs are not additional costs. Additional costs (resulting from the measures to reduce emissions) are estimated to be €4bn/year in pathway 1 and €3bn/year in pathway 2 (see page 69 of the report). To enable the investments, the government must ensure that “the energy system and the associated infrastructure are developed timely alongside the transition”, say the report. It must also “work towards a global level playing field;” if that cannot be achieved, it must “provide the necessary financial support.” |

How will the gas industry evolve in the low-carbon world of the future? Will natural gas be a bridge or a destination? Could it become the foundation of a global hydrogen economy, in combination with CCS? How big will “green” hydrogen and biogas become? What will be the role of LNG and bio-LNG in transport?

From his home country The Netherlands, a long-time gas exporting country that has recently embarked on an unprecedented transition away from gas, independent energy journalist, analyst and moderator Karel Beckman reports on the climate and technological challenges facing the gas industry.

As former editor-in-chief and founder of two international energy websites (Energy Post and European Energy Review) and former journalist at the premier Dutch financial newspaper Financieele Dagblad, Karel has earned a great reputation as being amongst the first to focus on energy transition trends and the connections between markets, policies and technologies. For Natural Gas World he will be reporting on the Dutch and wider International gas transition on a weekly basis.

Send your comments to karel.beckman@naturalgasworld.com