Improving fortunes for Indonesian gas? [LNG Condensed]

In a significant turnaround, the government of Indonesia says that plans to import LNG have been cancelled. The minister for energy and mines, Ignasius Jonan, says the country will now “never” need to import gas, owing to several big projects being developed after many years of delay.

However, domestic demand is set to grow rapidly as the government seeks to increase the share of natural gas in the energy mix to maximise oil exports, so the gas industry is coming under demand pressure from both sides. At the same time, the crash in oil and gas prices threatens the economic viability and timing of Indonesia’s new upstream projects.

Declining exports

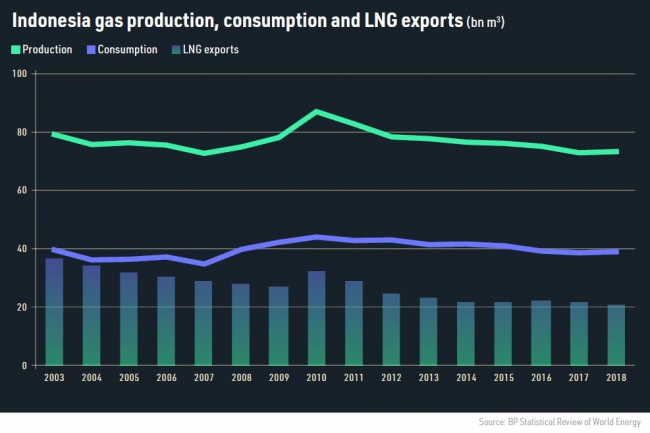

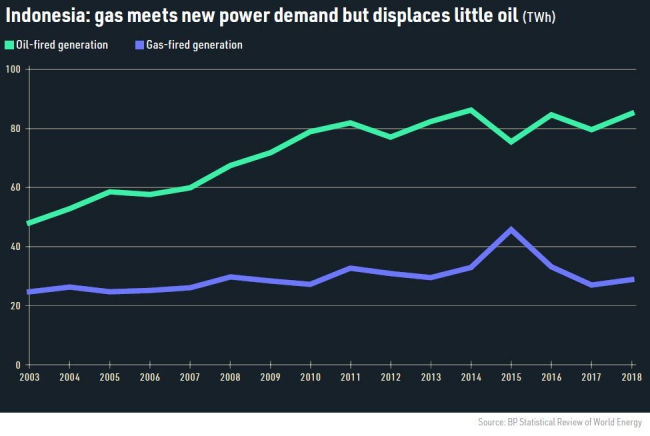

Indonesia’s position as a global LNG power has been steadily eroded since it controlled 40% of the global market in 1988. It now accounts for just 6% of global supply. Falling export volumes are not just a function of failings in the oil and gas sector, but the result of economic growth over the past 20 years, resulting in higher domestic energy consumption, with gas demand increasing in particular from gas-fired power plants and industrial companies.

The country has three operational LNG plants. The biggest is state-operated Badak LNG in Bontang, which has production capacity of 11.5mn metric tons a year from four trains, followed by Tangguh with 7.6mn mt/yr from two trains; and the single-train Donggi-Senoro, which was completed in 2015, with 2mn m/yr capacity. However, exports have declined as more gas output and also LNG production has been funnelled into domestic use.

LNG exports fell from 23.6mn mt/yr in 2010 to 13.4mn mt/yr in 2018. Declining production on the Arun field in North Sumatra led to the Arun LNG plant being converted into a regasification terminal in 2014. Many of the country’s long-term supply contracts expired over this period.

Indonesia also began to eat into its own LNG production, joining the select but growing band of countries with both LNG liquefaction and regasification terminals. In 2012, the Nusantara floating, storage, regasification unit (FSRU) was completed with capacity of 3mn mt/yr. The Lampung (1.8mn mt/yr), Arun Regas (3mn mt/yr) and Benoa (300,000 mt/yr) projects have since followed.

Abadi LNG at last

Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo announced plans in early 2019 to introduce new oil and gas sector legislation to encourage greater investment, after years of criticism over the level of red tape. Foreign firms have also complained about unattractive investment terms, with the result that planned projects have been repeatedly delayed or cancelled.

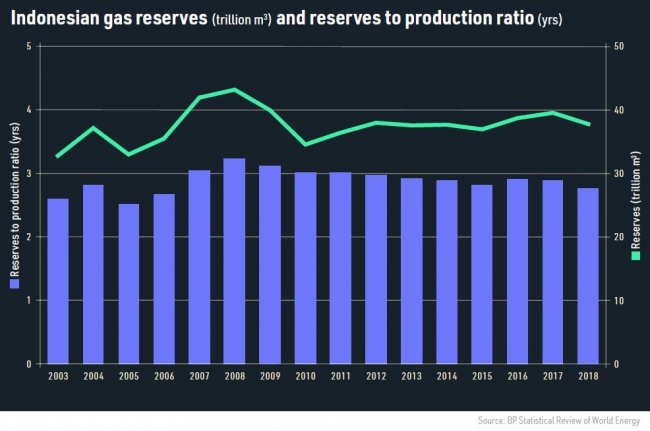

As a result, Indonesia has failed to make the most of its 98 trillion ft3 of proven natural gas reserves, while oil production had also dropped steadily. Yet the planned new law has still not materialised.

Nonetheless, after years of decline, the government is now confident there will be sufficient gas to support the development of new LNG production capacity and increase the use of existing plants.

The biggest boost to the industry looks set to come from Inpex’s Abadi LNG scheme on its Masela block, south of the Tanimbar Islands and right on the maritime boundary with Australia. The Japanese company, which began exploration work on the block in 1998, originally planned to develop the field as a floating LNG (FLNG) project, but this was blocked by the government in 2016, forcing it to investigate onshore options.

Inpex now holds a 65% stake in the venture, with Shell owning the remaining 35%. Their project development plan for a 9.5mn mt/yr onshore plant, including the timetable, level of investment, financial terms and local supply, was sanctioned by the government last year.

Yet no final investment decision (FID) has been taken, with Inpex saying, prior to the current drop in oil prices, that it hoped to take FID in the early 2020s, which implies first gas sometime after 2027. Project capital costs are estimated at 2 trillion yen ($18.4bn).

This would be the second big LNG project developed by Inpex, after it brought the Ichthys scheme on stream in Australia in 2018.

Inpex has already awarded a contract to Fugro to undertake a geophysical and geotechnical marine survey to support front-end engineering design (FEED) work on the offshore production infrastructure and pipeline.

There are believed to be a variety of engineering challenges on the project, including regional seismicity, subsea faulting and slope stability. The partners are also in talks over concluding long-term sales and purchase agreements for LNG from the onshore plant.

However, a significant proportion of the development’s output will go to meet domestic demand rather than exports. In February, the Japanese firm’s local subsidiary, Inpex Masela, signed memoranda of understanding with state-owned power company PT Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN) and PT Pupuk Indonesia concerning the supply of both LNG and natural gas to the domestic market.

This includes 150mn ft3/d of natural gas to a fertiliser and petrochemical project owned by Pupuk Indoneisa; and 2-3mn mt/yr of LNG to a gas-fired power plant operated by PLN.

In a statement, Inpex said: “The long term supply of LNG and natural gas from the project is consistent with the Indonesian government’s focus on optimizing domestic natural resource utilization.”

Upstream prospects

BP is currently developing the Tangguh LNG Train 3 in West Papua with annual production capacity of 3.8mn mt/yr. This will increase total production capacity on Tangguh to 11.4mn mt/yr.

The field, which had proven reserves of 18 trillion ft3, was discovered in the 1990s and brought into production in 2009. Train 3 was due for completion this year, but engineering and procurement problems have been reported and it is now likely to be the second half of 2021 before it is completed.

The government’s Upstream Oil and Gas Regulatory Special Task Force (SKK Migas) has attributed the delay to a contractor’s financial problems and the impact of natural disasters on the production of construction materials.

The Bontang LNG plant could benefit too, if the Gendalo-Gehem project, which is the second phase of the Chevron-operated Indonesia Deepwater Development (IDD), were developed. Until recently it looked like it would be, as talks were underway between Chevron (62%), Eni (20%), a variety of smaller investors (18%) and SKK Migas over developing the project, with first gas targeted from the new development phase for 2025.

The first phase, named Bangka, came on stream in 2016, with an estimated 1 trillion ft3 believed to be in place, while Gendalo-Gehem holds an estimated 1.5 trillion ft3.

However, Chevron announced in January that it was considering selling its stake in IDD. In a statement, it said: “IDD Stage 2 was not able to compete for capital in Chevron’s global portfolio.”

Analysts GlobalData said in February that production from gas fields that supply existing LNG plants will decline over the next six years, but that gas supplies to LNG production could recover sometime after 2026 if the Abadi and Gendalo-Gehem LNG projects were developed as planned.

In addition, more gas could be fed into the domestic market from the Kali Berau Dalam discovery that was made on the Sakakemang Block in South Sumatra last February. The Spanish company Repsol, which has a 45% stake in the licence, estimates reserves at 2 trillion ft3, making it the largest gas discovery in Indonesia in 18 years. Petronas holds 45% and Mitsui Oil Exploration 10%.

If sanctioned, it could come on stream within five years.

Meanwhile, Badak LNG should have a new source of supply when the Merakes deepwater gas field comes on stream next year. Located just 170km from the plant, it is operated by Eni with an 85% stake, alongside Pertamina (15%). In addition, Pertamina’s Jambaran Tiung Biru project in East Java is scheduled to come on stream in the second half of next year. It will supply 170mn ft3/d to power plants from 2.5 trillion ft3 of reserves, helping to ensure domestic supply so that more LNG can be exported.

Government ambitions

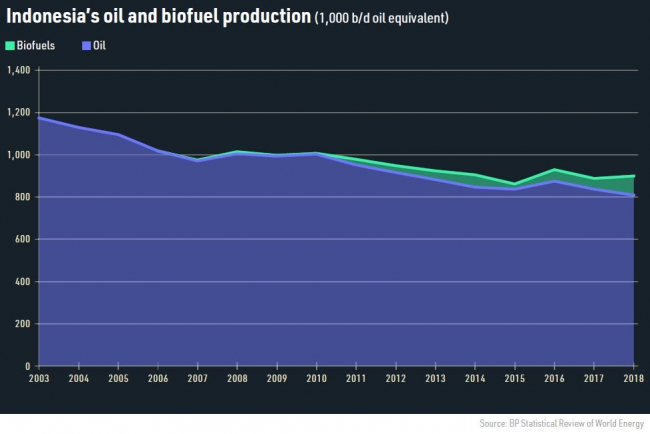

Enthusiasm surrounding the various projects has prompted the government into setting a target of doubling natural gas production to 12.3bn ft3/d by 2030. This sounds like a very ambitious target, particularly as government officials have said that domestic demand would continue to take priority over LNG exports, with the domestic market taking 70% of total output by 2024, up from 35% at present. A separate target of boosting oil production from an average of 746,000 b/d last year to 1mn b/d by 2030 has also been set.

The government is particularly keen to boost hydrocarbon production to reduce the country’s growing deficit in oil and gas. The country had a $1.18bn deficit in oil and gas trade in January, almost three times as much as in the same month last year. Without it, the country would have had a surplus in overall trade, rather than the $864mn deficit it recorded for the month.

Total oil and gas revenues were $805.9mn this January, 34.7% lower than in the same month in 2019. The collapse in oil and gas prices in March will therefore serve to improve Indonesia’s overall trade balance, but limit funds for upstream development while making project economics highly uncertain.

Domestic gas demand

Djakarta has set a target of increasing the proportion of gas in the energy mix from 18.1% in 2018 to 22% by 2025. Given that SKK Migas forecasts a rise in total energy consumption from 185.5mn mt/yr of oil equivalent to 248.4mn mtoe over the same period, this would require a big absolute rise in gas demand and supply over the same period.

The government wants more gas-fired generation capacity and more power from renewable energy projects to reduce the share of oil in the energy mix from 45% in 2018 to 25% by 2025. A big increase in biofuels and using LNG as a fuel for trucks is planned to help achieve this highly ambitious target. The strategy is designed to prolong the life of the Indonesian oil industry; some reports suggest that existing fields could be exhausted by 2030 at current rates of recovery.

The state-owned gas transmission and distribution firm Perusahaan Gas Negara (PGN) has been given the task of ensuring that more gas-fired plants are developed. The government restructured the energy sector in 2018 to give Pertamina a 57% stake in PGN to ensure the smooth development of gas projects from field development, through pipeline construction and on to distribution.

PLN will convert some of its power plants from oil and diesel to gas, starting with 52 very small diesel-fired plants with combined capacity of 1,870 MW. PLN plans to reduce its diesel consumption from 2.6mn kilolitres last year to 1.6mn kilolitres in 2021.

In early March, PGN announced that it would invest $2.5bn in regasification capacity and associated infrastructure in Nusa Tenggara, West Kalimantan, North Papua, Sulawesi and Maluku to supply gas to its power plants.

This policy of displacing oil with gas in the power sector could have a big impact on the country’s ability to export LNG. However, much will depend on the impact of Covid-19 on long-term economic growth and therefore energy demand.

At present, it appears that it could have a dramatic effect on growth over the forecast period. Shipments of LNG from Indonesia’s Tangguh plant to China’s Fujian province were already being postponed in February because of the outbreak. At this stage, cargoes have just been delayed by several months, but it seems likely that some will be cancelled entirely.

Future prospects

In a price environment capable of supporting upstream investment, a turnaround in Indonesian LNG exports looks possible, but current plans are almost certain to be held in abeyance until there is at least some stabilisation in the oil price.

The government had previously expected to start importing LNG by 2025, but the planned contract for Cheniere Energy to ship cargoes from its plant on the US Gulf coast to the Nusantara FLNG plant may now be cancelled. However, it remains to be seen if the rise in exports will be quite as dramatic as the government hopes because of the rapidly growing demands of the power sector.

Producing 1mn b/d oil and 12.3bn ft3/d of gas by 2030 is a very testing target, particularly as just two years ago the General National Energy Planning road map for the country’s energy future forecast falls in oil and gas production over the next decade, to 667,000 b/d and 5.8bn ft3/d by 2030 respectively. Further gas discoveries need to be made, if LNG exports are to be sustained, as demand from the power and petrochemical sectors is continuing to grow.

Indonesia should have the LNG capacity needed to boost exports if the feedstock is available. If Masela and Tangguh Train 3 are developed as planned, they would boost national production capacity to 33.1mn mt/yr.

Post Covid-19, there is likely to be plenty of appetite for Indonesian LNG, if output rebounds as much as the government hopes. Given its geographical location, almost all of Indonesia’s exports go to the huge LNG markets in East Asia: Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and China.