Indian LNG faces quandary [LNG Condensed]

Natural gas is seen as one of the key ways of reducing India’s high dependence on coal and mitigating the severe environmental problems caused by its use. In 2019, coal accounted for 55% of total Indian primary energy supply and 73% of its overall electricity generation, according to the BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2020.

The government’s strategy for reducing coal production and use is based in part on large-scale investment in renewable energy. The targeted installation of 510 GW of solar, wind, hydro and other renewable capacity by 2030 is officially projected to meet 60% of national electricity requirements in that year. But implementing the coal-reduction strategy is also predicated on raising gas’s share of total primary energy supply from 6.3% in 2019 to 15% in 2030.

The government reiterated its commitment to achieving the 15% goal on January 5, when Prime Minister Narendra Modi said that over the period to 2024 some $60 billion would be invested in gas infrastructure. This would include completion of the construction programme for 16,000 kilometres of trunk pipelines that began in 2014, as well as spending on city gas distribution networks, 10,000 compressed natural gas (CNG) fuelling stations, and LNG import terminals.

The government’s target for gas use will require a very substantial and rapid increase in gas demand from the 59.7bn m3 consumed in 2019. Consultants Wood Mackenzie estimated in October 2020 that gas use would have to rise almost three-fold to 170bn m3 to meet the 15% target in 2030.

Domestic production falters

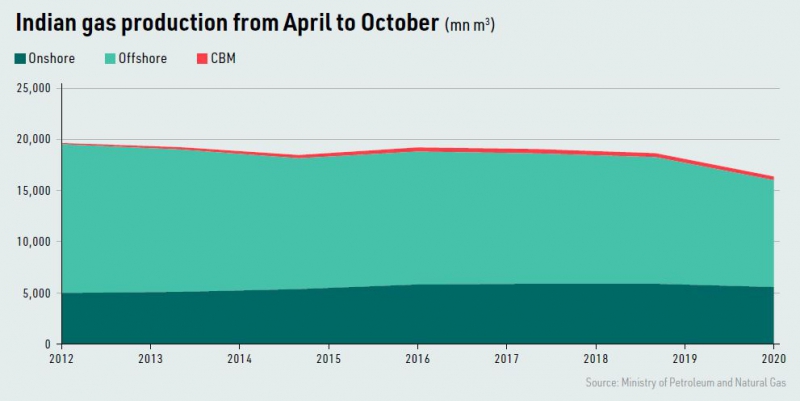

Most of that additional demand will have to come from imports. Indian natural gas production has declined markedly over the past decade, with output falling from 47.4bn m3 in 2010 to 26.9bn m3 in 2019. The period did see some growth in onshore production, while coalbed methane extraction also increased, albeit from a low base.

However, these gains were more than offset by a slump in offshore production, driven by problems in the KG-D6 block of the Krishna Godavari basin. Offshore output almost halved in the April to October period of 2020, compared with the same seven-month period of 2012, and was 15.7% lower than for the same period in 2019.

The 2020 decline in gas production partly reflected the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on economic activity and energy use. Indian gross domestic product fell by 7.7% year on year in the April to October period, while industrial production fell 15.5% on year from April to December.

Gas output had already been hit by lower, pandemic-affected demand from the industrial and other sectors towards the end of the financial year to March 2020, with annual production of 31.17bn m3 being the lowest recorded for two decades. But the long-run decline in Indian offshore output remained the underlying reason for the year-on-year fall in 2020.

That said, some reversal of the long slide in Indian offshore gas production is likely in the future. The development by a 67/33 joint venture between the local Reliance Industries Ltd and BP of the R Cluster deep-water field in KG-D6 has been completed, with gas due to be sold from February and output expected to plateau at 12.9mn m3/d.

The R Cluster will be followed this year by the Satellites Cluster and in 2022 by the MJ project. Output from the three projects, which have access to some 85bn m3 of resources and cost about $6 billion, is expected to reach 11bn m3 in 2023.

Nor are these projects isolated. For instance, ONGC is developing a separate suite of deep-water projects in the KG Basin that could produce up to 30bn m3 by 2024.

LNG imports to rise

However, these and other new developments appear unlikely to keep pace with the projected growth in gas demand. To achieve its social and economic growth objectives, India will have to become more reliant on imports, which at least in the near to medium term means more LNG.

While the country has looked at importing gas from central and west Asia through cross-border pipeline projects for many years, few of the projects have made much progress. For instance, developments were reported sporadically in 2020 on the 33bn m3/yr Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India project, but its implementation remains no more probable than over the past decade, not least in the case of India because of the security risks associated with its route.

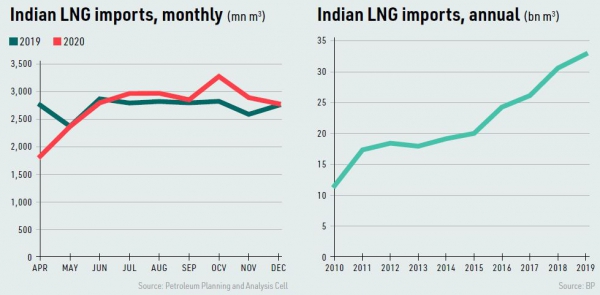

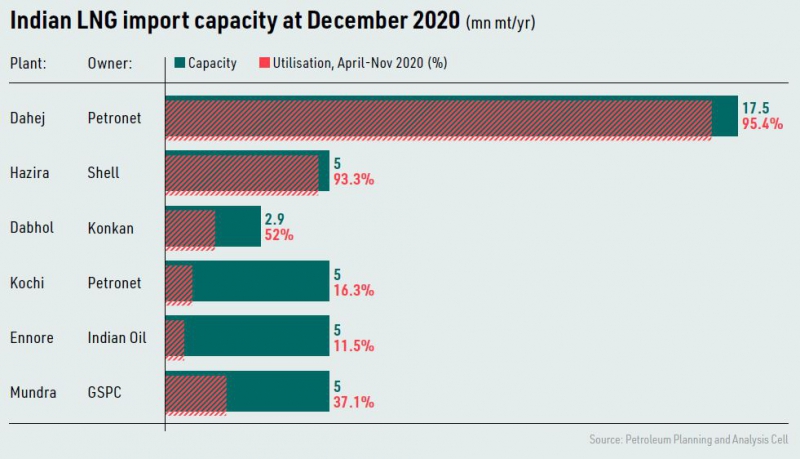

That has left the field open to LNG. India’s stock of operational LNG import terminals has increased to six with combined capacity in excess of 40mn mt/yr (55bn m3/yr), while a large number of other projects are at various stages of development. LNG imports almost tripled from 11.5bn m3 in 2010 to 32.9bn m3 in 2019, according to BP data.

Indian LNG imports continued growing in the last nine months of 2020, despite the pandemic-induced slump in economic activity. LNG imports from April to December grew by 0.7% year on year to 24.75bn m3. The 5.3% year-on-year fall in gas consumption to 45.2bn m3 during this period was more than offset by the 11.3% year-on-year drop in domestic gas output to 21.1bn m3.

The growth in imports was assisted by the fact that for much of the period the global LNG market was awash with large volumes of low-priced spot cargoes.

The Indian economy recorded a marked uptick towards the end of 2020 with, for instance, industrial production being down only 1.9% year on year in December. With energy demand indicators also moving upwards this suggested Indian LNG demand would grow strongly.

Price sensitivity

However, international spot LNG prices jumped at the end of the year. A surge in North Asian demand resulting from cold weather coincided with supply disruptions and some production constraints to push prices to record levels. Indian activity in the market dropped sharply thereafter, with several planned tenders for spot LNG being cancelled because of a lack of acceptable price offers.

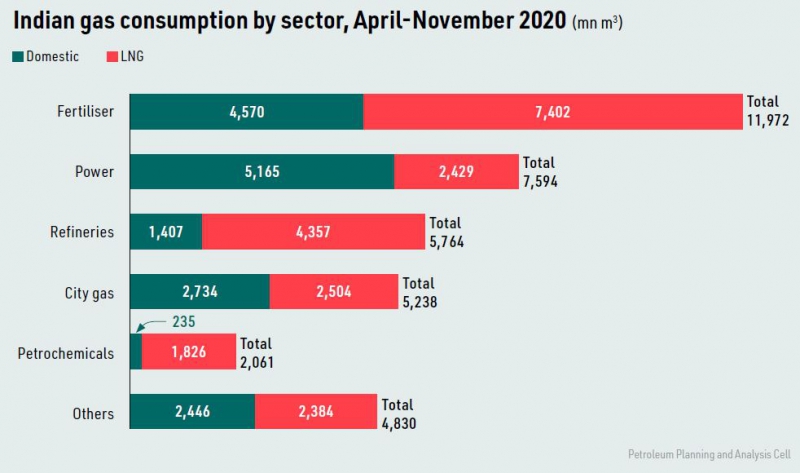

One of the main issues here is that a large part of Indian gas is consumed in sectors which sell their products on the basis of artificially low, controlled prices. The fertiliser sector, which consumes around a third of Indian gas, has been one of the main problem areas in this respect. It has usually sought gas -- whether domestic or imported – at a price which is below cost when netted back to the gas supplier. And where fertiliser producers have paid a market price for gas, payment problems have occurred when government subsidies were delayed or not forthcoming.

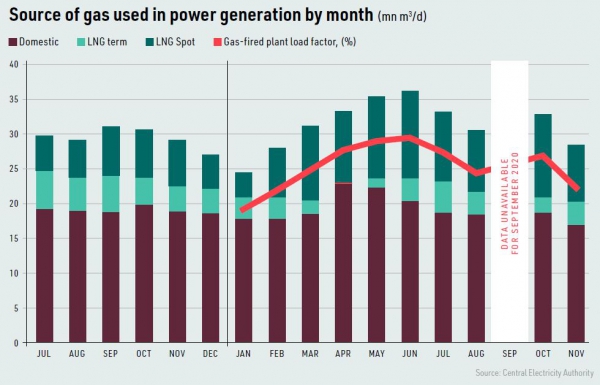

Gas sales to the Indian electricity generation sector have also had their fair share of problems as a result of controlled retail prices, but a key issue in the sector at present is the competition from power generated from low-cost coal and renewable energy plants. This is one of the reasons why the plant load factor of India’s 24 GW or so of gas-fired capacity is generally low at 25% or less – use of the fuel is uncompetitive at realistic gas prices.

The low spot prices prevailing for most of 2020 did see Indian gas-fired generation increase as more spot LNG was burnt. This helped push gas-fired output over the period from April 2020 to January 15 this year to about 13% above the planned level for the period.

Spot LNG accounted for a third or so of gas burn in several months including June and October, according to data from the Central Electricity Authority. This was well up on previous years, with much of the gas use involving spot purchases burnt in Gujarat state. However, the subsequent price rise is expected to curtail gas-fired generation again.

How gas use evolves in the power sector in the next few years will be the key factor determining whether India can meet its 15% target for gas in 2030. Electricity generators use much larger amounts of additional gas than individual consumers in sectors such as industry and transport. They also already own a substantial amount of operational, but under-utilised capacity with existing links to the gas distribution network and LNG import terminals.

The additional gas burn could also have a direct impact on reducing coal pollution, while gas-fired generators operating on intermediate load can help balance grids that will be increasingly reliant on supplies from renewable energy plants.

However, to ensure sufficient additional gas is used these advantages will need to be factored into the relative price of gas-fired and other generation, for instance through carbon pricing and other measures to penalise coal use, or through payments for grid support. This will, in turn, largely determine how much additional LNG is imported, and whether the preference is for more term or spot volumes of the fuel.

Gujarat state, where 25% of energy demand is already met by gas, shows that the 15% target for 2030 is attainable, if the necessary infrastructure and energy pricing structures are put in place.

How much gas is used and LNG imported over coming years will come down to whether individual states and the country as a whole make more progress in these respects. Recent initiatives suggest moves are being made in the right direction, including the decisions to unify trunk pipeline tariffs and scrap domestic output price ceilings.