Interview: Anne-Sophie Corbeau [NGW Magazine]

NGW had the opportunity to meet BPs’ chief gas analyst Anne-Sophie Corbeau during IP Week in February in London.

NGW asked her about natural gas, future threats, impact of trade wars, methane emissions, impact of energy storage technology and the role of the gas industry by 2050.

NGW: Bob Dudley said at IP Week that world energy is driven by myth versus facts and that it is important to stay with facts, by putting a simpler story together. How is BP putting this simpler story forward for natural gas?

A-S C: I can’t speak on behalf of Bob, but from an economics perspective, which is my area of expertise, we are very transparent in terms of data. This year we will publish the 68th edition of the BP Statistical Review, which provides historical energy data. It has been improved over time: last year, we added more details on power generation as well as data on some energy-relevant metals such as lithium.

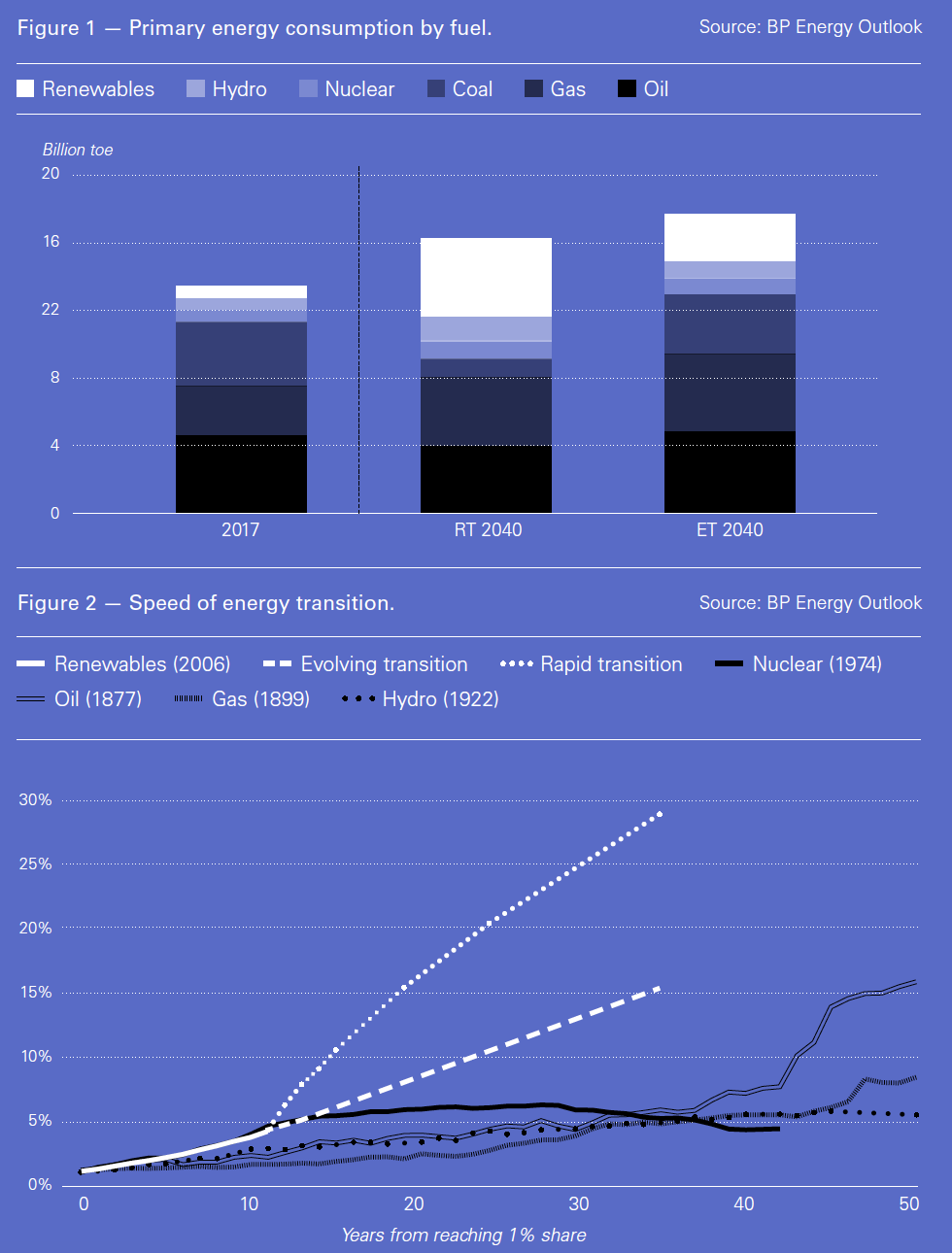

We also publish the BP Energy Outlook which looks at the energy transition through different scenarios to 2040. In all the scenarios we looked at this year, natural gas remains a key part of the energy mix. It is the only fuel besides renewables whose share rises in all scenarios.

In the Rapid Transition (RT) scenario – the only scenario which shows CO2 emissions reductions broadly in the middle of a range of external projections which claim to be consistent with meeting the Paris Climate goals -- natural gas demand increases by over a third (Figure 1) as gas replaces coal in the power and the industrial sectors. This is only possible with a growing use of carbon capture, use and storage (CCUS) – by 2040, over a third of gas is used in conjunction with CCUS.

Moreover, all the data behind our graphics in the Energy Outlook as well as key data for the scenarios are available on our website (www.bp.com).

NGW: BP’s Energy Outlook forecasts that global primary energy demand will grow by one third by 2040 as Asia becomes more prosperous, with gas demand increasing by 50%. Others dispute this on the basis that renewables and energy efficiency will do better than BP suggests. Could these be a threat to future gas demand?

A-S C: This outcome is that of the Evolving Transition scenario (ET). This scenario looks at what happens if societal, technology and policy changes continue to evolve in a manner and pace observed over the recent past. This is not what we think is going to happen, but is a projection of what could happen if society, technology and policy changes continue in a similar manner to the recent past. This is also not a scenario likely to be consistent with meeting the Paris climate goals, which implies that the world needs to do more and at a faster pace than what we are currently doing to substantially reduce CO2 emissions.

_f250x250_1556718080.jpeg) In the Rapid Transition scenario, we have very strong growth of renewable energy, which reaches almost 30% of primary energy demand by 2040. For example, renewables represent almost half of the electricity generated in all of Asia, compared with just 7% today; and the continent uses almost twice as much electricity.

In the Rapid Transition scenario, we have very strong growth of renewable energy, which reaches almost 30% of primary energy demand by 2040. For example, renewables represent almost half of the electricity generated in all of Asia, compared with just 7% today; and the continent uses almost twice as much electricity.

The chart in the Energy Outlook shows the speed of energy transition and highlights the fundamental change required. This is unlike anything we have seen since the 19th century. It took 45 years for oil to reach a tenth of primary energy demand from the moment it reached 1% in 1877. In the Evolving Transition scenario, renewables reach 10% in around 25 years. In the Rapid Transition scenario, it happens in around 15 years (Figure 2).

That’s huge growth. And much faster penetration than any other fuel in history.

As for energy efficiency, strong assumptions are already embedded in the Evolving Transition scenario. For example, efficiency of ICE (internal combustion engine) cars in that scenario increase almost 50% over the Outlook period. In the Rapid Transition scenario, we push not only efficiency in processes but also assumptions in terms of circular economy. Energy demand under those conditions still goes up by around a fifth over the 2017 to 2040 period, and gas grows at a slower pace than in the Evolving Transition scenario but it is still growing by around one-third.

NGW: Bob Dudley also said “We will solve the energy transition problem.” How and how does natural gas comes into this?

A-S C: At BP we talk a lot about “the dual challenge” of providing more energy to meet the needs of a growing population and to help people lift themselves out of poverty and low incomes while also reducing carbon emissions.

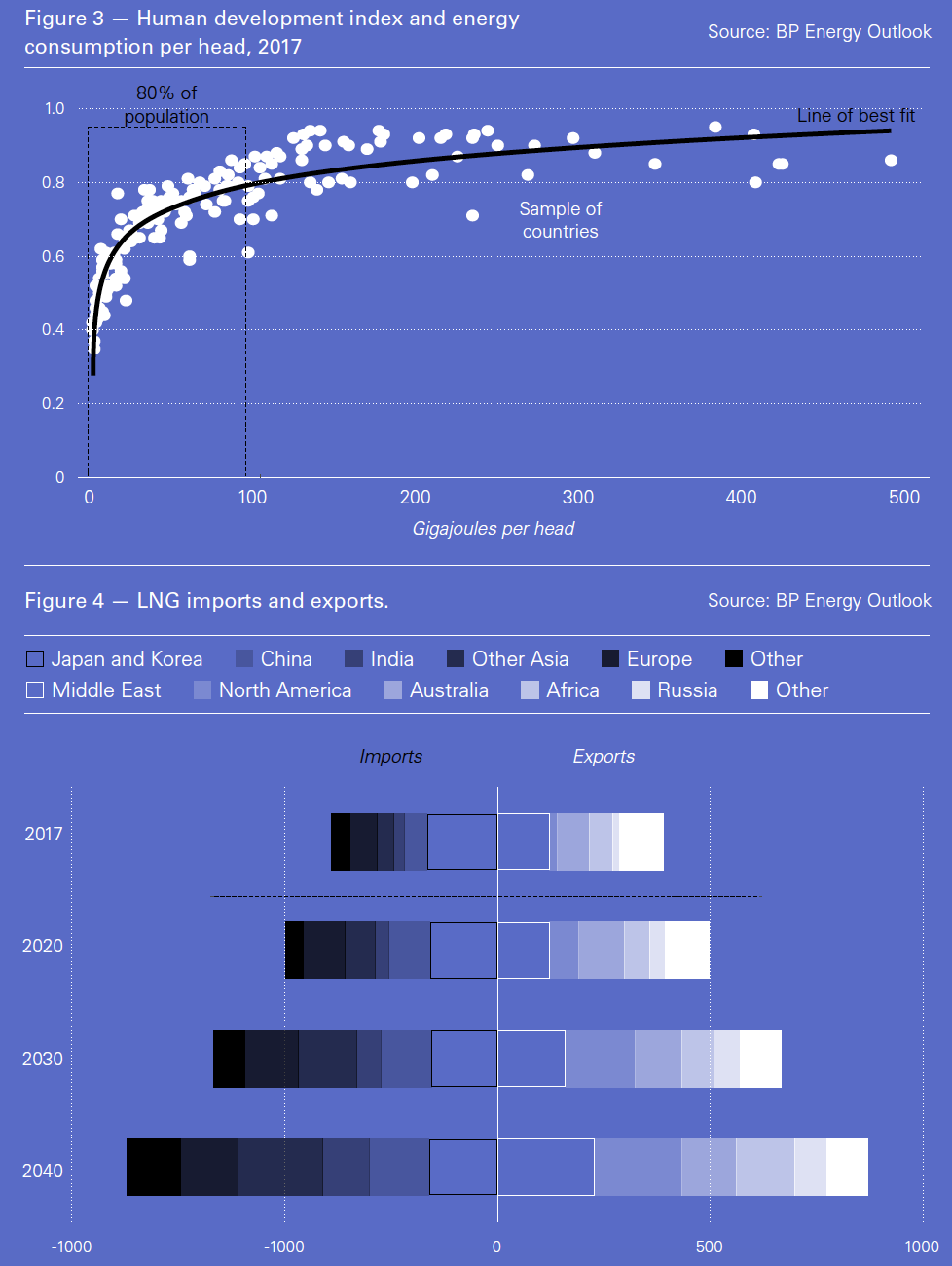

The world needs more energy. There are still around 1bn people without access to electricity and almost 3bn without access to clean cooking. A very striking fact: four in every five people live in countries where rises in energy consumption per capita tend to go hand-in-hand with significant improvements in living standards (Figure 3). The Paris climate goals include reducing emissions rapidly and the goal of reaching net zero emissions in the second half of this century needs to be made in the context of sustainable development and efforts to eradicate poverty.

Energy demand is set to increase in developing countries. Renewables have a key role to play; as mentioned before they are growing faster than any fuel in history. They represent a third of primary energy demand in the Rapid Transition scenario, but that means that around two-thirds of the world’s energy needs have to come from other sources of energy.

Gas has a key role to play in this process: it is abundant, affordable and accessible. Thanks to its cleaner-burning properties and in combination with renewables, it can reduce coal consumption in power and industry.

NGW: Is BP becoming a natural gas company and if so is it taking a risk?

A-S C: BP’s upstream strategy is to grow gas and advantaged oil. The world will continue to need significant amounts of oil and gas for decades. While we are also investing in new technologies and alternative energies, we think gas is part of the solution to the dual challenge, by bringing more energy to those who need it and by being a cleaner burning fuel and a complement to renewables. It can also bring significant improvements in air quality when used instead of coal, as we have seen in China.

NGW: In Asia trade wars and sanctions have brought energy security and maximisation of domestic energy production and use to the fore. This does not appear to have been factored in recent LNG demand forecasts. Could this dampen LNG demand? Does it affect BP’s plans?

A-S C: Global gas trade increases sharply by around 80% over the Outlook period in the Evolving Transition scenario. This includes LNG as well as interregional gas trade (but not pipeline trade within regions). In particular, LNG trade more than doubles from 390bn m3 in 2017 to 870bn m3 in 2040, supported by the expansion of LNG supplies in the US, Africa, Middle East and Russia, while Asia remains a key importing region (Figure 4).

In the Energy Outlook 2019, we looked at an alternative scenario called Less Globalisation, which features an escalation of trade disputes at a global level. The consequences on the energy system are quite significant: energy demand by 2040 is about 4.5% lower than in the Evolving Transition scenario – that’s roughly the size of Indian energy demand today. This is because the global economy grows at 0.3%/yr less than in the Evolving Transition scenario. The scenario also assumes that importing countries put a 10% risk premium on imported sources of energy as concerns about energy security rise. This impacts directly traded energy including natural gas, oil and coal. In fact, demand for natural gas in the Less Globalisation scenario ends up being marginally lower than in the Rapid Transition scenario by 2040. Exports of natural gas from the US and Russia are particularly impacted.

NGW: How are you dealing with methane emissions and with reducing your carbon footprint?

A-S C: BP is taking a leading role in addressing methane emissions. We are targeting a stringent methane intensity goal of 0.2%.

As you may have heard during CERAWeek, BP has announced a three-year partnership with the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) on developing technologies and management practices to accelerate reductions of methane emissions across the global oil and gas industry. We hope that this collaboration will facilitate industry dialogue about the best practices to monitor and reduce emissions.

NGW: There is general agreement within the hydrocarbons industry that natural gas is the fuel of the future during energy transition and beyond. How do we make it happen?

A-S C: Natural gas demand increases in all our scenarios. This is supported by: increases in regions endowed with lower cost resources such as North America, and the Middle East; regions with rapid economic development, such as developing Asia and Africa; and regions which have put in place policies to support natural gas – like China, where demand has risen substantially over the past two years thanks to coal-to-gas switching. Such policies are very important, but natural gas also needs to be supported by the development of infrastructure to grow – whether this is pipelines, distribution or import infrastructure – so that it can be available to final users.

It is also important to note that natural gas brings a reduction of carbon emissions. This can happen when one switches from coal or oil to natural gas in various sectors, but in particular in power generation. The greater use of biogas also allows the overall emissions of gas to be reduced. Finally, hydrogen seems to have a high potential to decarbonise various parts of our energy system, notably those that are more difficult to decarbonise from buildings, industry and transport. Hydrogen can be produced either by electrolysis or by steam reforming/autothermal reforming with CCUS. The choice of one or the other solution will vary by country, depending on the cost of the different energies and the specifics of the energy system. In the short term, it is important to enable the development of hydrogen-based solutions in a technology neutral way.

NGW: Energy storage technology is making rapid progress increasingly threatening use of coal and natural gas in power generation. Is this allowed for in the scenarios in the Energy Outlook and what is the potential impact?

A-S C: There is some increase in battery storage in the Energy Outlook scenarios. But the level of penetration of renewables in most parts of the world in the Evolving Transition scenario means that the level of intermittency is relatively limited. Moreover, in the Rapid Transition scenario, the use of gas-fired power stations with CCUS provides a natural source of balancing for renewables.

NGW: An increasing number of countries are committing to net-zero or near-zero emissions by 2050, including the EU. None of the scenarios in the Energy Outlook go that far. Is it achievable; and should the natural gas industry be factoring this in?

A-S C: We are not looking at 2050 yet in the Energy Outlook. We have only recently moved the Energy Outlook from 2035 to 2040.

Whether this is achievable or not will depend on developments including the policy and technology progression. In the Rapid Transition scenario, we reduce CO2 emissions in the EU from around 3.5 Gt to less than 1 Gt by 2040. For natural gas, that means that demand is about a third lower by then. What remains in terms of CO2 emissions are the hard-to-abate sectors, particularly in industry and transport.

The natural gas industry still has a role to play, for example with blue hydrogen used in industry or long-haul transport. There is also a role for bioenergy, including biogas in places where natural gas is currently used, allowing the existing gas infrastructure also to be used.