Interview Friedbert Pflüger, Chairman, Supervisory Board. Zukunft Gas [Gas in Transition]

In Germany in the first half of 2021, for the first time ever, natural gas was the largest source of energy. According to Friedbert Pflüger, the new chairman of the supervisory board of German gas association Zukunft Gas, “it’s becoming increasingly clear that gas will continue to play a key role in the German energy mix for the foreseeable future”. Pflüger says the gas industry should get ready to convert its processes to hydrogen and that European politicians should concentrate on making Green Deals with countries like China and Russia.

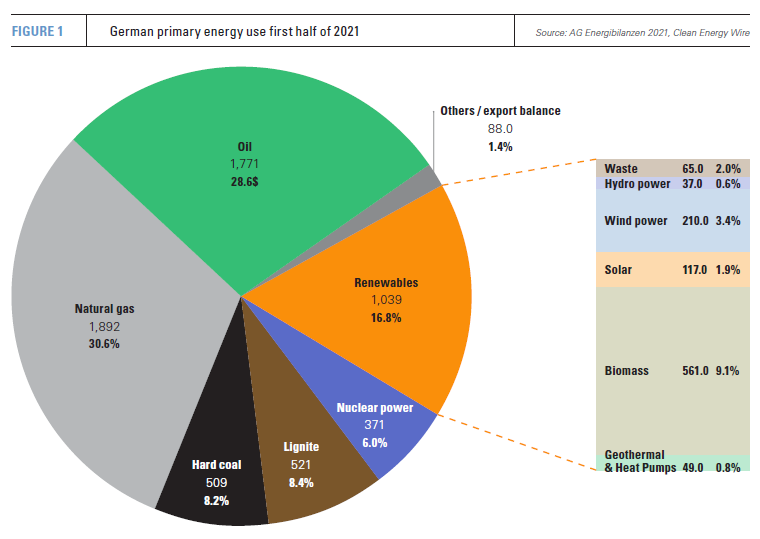

Germany was in for a surprise in August when figures were published on primary energy consumption for the first half of 2021. Natural gas consumption grew by no less than 16% compared to the year before. For the first time ever, gas became the largest source of energy with a share of over 30% – this in the country long known for its reliance on coal power andmassive investments in renewables.

For Dr. Friedbert Pflüger, the new chairman of the supervisory board of industry association Zukunft Gas (“Future Gas”), the success of gas did not come as a great surprise. Pflüger, who is one of the most experienced personalities in the German energy sector and active in political, academic and business circles for four decades, explains that in the present circumstances Germany has little alternative but to use gas. “We are phasing out nuclear by 2022. But in the south, for example in Bavaria, they still need energy. The transmission lines to take renewable energy from north to south are not in place and they have not sufficient space for wind and solar. The only thing that can jump in: gas.”

In addition, Pflüger notes, there has been pressure to reduce coal power consumption. “We have decided to phase out coal by 2038. Already the government has put in place high CO2 prices. That stimulates coal to gas switching.” There is no other alternative, says Pflüger. “It is becoming increasingly clear that gas will play an important role in the German energy mix for the foreseeable future. If you want security of supply, you cannot do without gas. Other European countries are in the same boat,” he adds.

Fact of life

Pflüger regrets that many green NGOs tend to regard fossil fuels as the enemy. “If we can make hydrogen from natural gas without CO2-emissions, why not? I hope the green movement is not a lobby for renewable energy? The Fridays for Future Movement says all fossil fuels are bad. But we need gas, that is a fact of life. 1.6 million companies in Germany are dependent on gas. Half of the German households do their heating with gas. It’s an enormous force in Germany. To substitute this for renewable energy will take a long, long time. It’s certainly not possible in the next 20 years.”

According to Pflüger, in the public debate in Germany, not enough cognizance is taken of the role of gas. “The paradigm is that fossil fuels are bad. I do not take issue with the aims of Paris. Climate change is indeed a matter of survival for humanity. But we have to look closer at how we can achieve our aims. We have spent $2.5 trillion on renewable energy in the world, but it still makes up only 3% of primary energy supply. I deeply believe we need to expand solar and wind power and bioenergy. But this alone will not get us there.”

He notes that in China last year the use of coal has grown again. “They are back at the level of 2013. What sense does it make to tell citizens in Germany they can’t fly from Munich to Berlin in this context?” We should talk less about targets for 2050, and more about reducing CO2 emissions in the next five years, says Pflüger. “What we need is a global fuel switch from coal to gas.” The German coal phase-out date, 2038, is too late, he adds, although it has now been agreed and should not be changed anymore. “CO2 pricing will ensure that the switch will be made gradually.”

Hydrogen-ready

But if gas is to play a key role, what exactly will it look like? How can it be aligned with climate neutrality? Pflüger’s answer is clear: “The future is hydrogen. In the long term the gas industry can only survive if we make all of our infrastructure and all our processes hydrogen-ready. The industry has been learning that lesson in the last two or three years. The gas bridge will be longer than most people think, but it will end.”

Pflüger observes that “even a giant like Gazprom is aware of this. I have met the new man in charge of Gazprom Konstantin Romanov. He is very smart, speaks English. He wants to change Gazprom to become a hydrogen producer. If they can find ways to produce hydrogen from gas in a carbon-neutral way, either through CCS or through methane pyrolysis, and to contain methane leakage, that will be a real breakthrough.”

He is convinced that “green hydrogen”, made from renewable energy through electrolysis, cannot be the only solution. “The German national hydrogen strategy aims at 90-110 TWh of hydrogen demand by 2030. But even if all existing projects go ahead, we will only get to 14 TWh. It’s utopia. Liechtenstein may as well declare that they want to win the World Football Championship in Qatar. That’s probably more realistic.”

Proven technology

Pflüger is optimistic about the future of CCS. “In Germany the Greens were completely against it. But now a green think tank like Agora Energiewende recognizes we need to put CO2 in the ground if we want to keep our cement, steel, chemical, and other industries in Germany. They still don’t want to do it inside Germany. But in countries like the Netherlands, Norway, UK, and Russia, there will be additional possibilities for CCS very soon. I think we will see more projects being announced. It’s a proven technology. It’s safe and it works.”

He is also positive about the possibilities of methane pyrolysis. “There are several research projects going on, for example at the Technical University of Munich. Wintershall and Gazprom are also working on it. Electrolysis cannot be our only option. It has its drawbacks. It is not energy-efficient and it uses a lot of water. Is it smart to start shipping green hydrogen from Africa, Saudi Arabia, even as far as Australia, all the way to Germany? How much will that cost?”

He is also positive about the possibilities of methane pyrolysis. “There are several research projects going on, for example at the Technical University of Munich. Wintershall and Gazprom are also working on it. Electrolysis cannot be our only option. It has its drawbacks. It is not energy-efficient and it uses a lot of water. Is it smart to start shipping green hydrogen from Africa, Saudi Arabia, even as far as Australia, all the way to Germany? How much will that cost?”

How would reliance on gas impact security of supply in Europe? Pflüger is an expert on this topic – he is the founder of the energy security think tank European Centre for Energy and Resource Security (EUCERS), formerly part of King’s College London, which has recently been brought under the umbrella of the Center for Advanced Security, Strategic and Integration Studies (CASSIS)

at the University of Bonn. He is not worried that Europe will become too dependent on Russia. “I have always been a proponent of diversification. I have been involved in several pipeline projects to bring gas from Central Asia to Europe. I have also been in favour of more interconnections, reverse flow possibilities and LNG terminals. We now have over 30 LNG terminals in Europe. If the Russians should want to use energy as a weapon, which I don’t think they will, but just in case, then we have alternatives.”

Nord Stream 2

Nord Stream 2, which has just been finished, will only add to the options Europe has to source gas, says Pflüger. It won’t diminish them. “Despite all the pressures from the US and the EU, Nord Stream 2 has been finished. I think that’s a major achievement. At the end of the day people will realise that we need this pipeline. Indigenous gas production is declining dramatically.”

Pflüger says “we talked about Nord Stream 2 much too long. We should have concentrated on how to make Russia greener. Through forestation, hydrogen, fostering renewable energy. Russia has great renewable resources. That would have been much more sensible and could really have made a difference to CO2 emissions.”

Pflüger says Europe should make a much greater effort to get Russia, China and other countries involved in its climate policies. “The EU Green Deal is alright as political objective, but it doesn’t say how we will achieve our objectives. If I were an advisor to the EU, I would recommend that they make more Green Deals. Between the EU and Russia, between the EU and China. We should enlarge the European approach to include these countries. Not by preaching, saying we know everything better, but by example, by offering technologies and investments, by smart climate diplomacy. Europe alone will not move the dial on CO2 emissions.”

There is a debate now in Europe about “carbon border adjustments” (taxes), to prevent “carbon leakage”, that is, to put a carbon price on goods imported from outside the EU, to protect European industries that might be outcompeted if they have to incur extra costs that their foreign competitors don’t. Pflüger does not believe this is a good idea. “Theoretically it sounds good. But it would be very difficult to implement. It would lead to a whole new bureaucracy that would be set up. It’s better to discuss with our industries how we can ensure they can stay competitive. We need to find ways for every industry to survive. If we offer green hydrogen as the only solution, we will fail.”

Pflüger notes that “carbon leakage” is already taking place. “Our GDP is growing, but our industrial base is becoming smaller. We will see more of this if we are not smart. This will make us more dependent on China and other countries.” He adds that “this is what I tell the Greens all the time. We need to reduce emissions, but we have to take jobs and industries into account. We have a consensus now on climate. If they become too radical, this could easily break down.”

Natural gas top source of energy in Germany

Germany's energy use in the first half of this year exceeded 2020 levels, as the economy recovered from the effects of the coronavirus pandemic, figures by energy market research group AG Energiebilanzen (AGEB) show. However, total energy consumption from January until June remained 7 percent below pre-pandemic levels in the first half of 2019, when adjusted for temperature.

Natural gas was the most important energy source for the first time, with a share of more than 30%. While fossil power production rose considerably compared to last year, it remained below 2019 levels for all sources except natural gas, additional figures from energy industry association BDEW show. The challenges for the transformation of the country's energy system towards renewable power sources became visible in the first half of 2021, when little wind and cold weather let green power production decrease. As fossil energy use increased, energy-related CO2 emissions rose by 6.3% compared to the same period the previous year, the researchers said.

The overall share of non-renewable energy sources in the country's mix grew in 2021, with hard coal spiking by nearly a quarter and lignite by almost a third. Lignite use was still 12% lower than in 2019. Nuclear plants produced 7% more electricity than in the year before while natural gas use for power and heating grew by 16%. Contrary to other fossil fuels, the use of mineral oil continued to drop in 2021, with consumption being 12% lower than in 2020, meaning oil's share fell below 30% for the first time ever.

Weather conditions also had a dampening effect on the share of renewable sources in the country's energy mix. Due to little wind in the first half of 2021, the renewables share fell by 1 percentage point, from 17.7% to 16.8%. Wind power saw its output drop by 20% compared to the particularly windy previous year, whereas solar power's contribution remained stable and that of hydropower and bioenergy grew by 5% and 6% percent, respectively.