Interview: Vincent Demoury, GIIGNL [Gas in Transition]

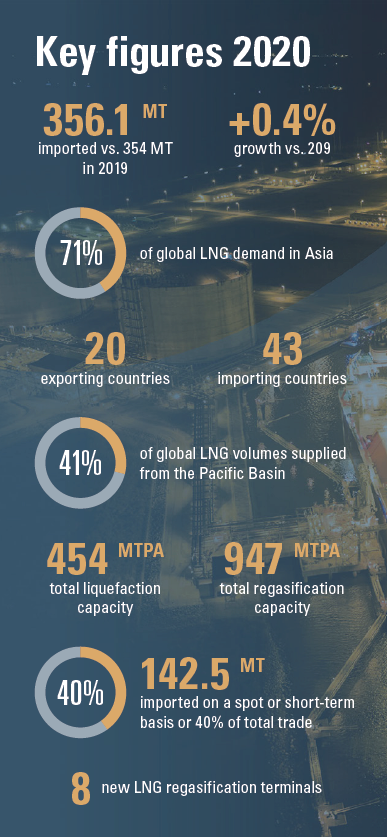

Scarred as it was by the COVID-19 pandemic, last year saw a much lower growth in LNG trade. The amount of LNG imported grew fractionally in 2020 from 354.7mn metric tons (mt) to 356.1mn mt, despite the shut-ins of production and the falling demand for energy, according to a new report by the France-based International Group of LNG Importers (GIIGNL).

On balance it was not at all a bad year for LNG, the organisation’s deputy general delegate Vincent Demoury tells NGW. After several years of compound annual growth rate nearing double digits, this 0.4% growth in volume from 2019 is comparatively small. “On the other hand, LNG was resilient, if you compare it with demand for other fuels over the same year, which fell,” he said.

New regasification capacity continued to come online, with eight terminals commissioned in 2020 in Bahrain, Brazil – which has two – Croatia, India, Indonesia, Myanmar and Puerto Rico.

“2020 was the first year that new regasification online exceeded new liquefaction since 2015. We do not see regasification as the bottleneck, all the more so as floating storage and liquefaction units (FSRUs) can be deployed relatively quickly. Regasification brings optionality: it can be used for storage as well as regasification and, with volatile prices, we also see more storage capacity being built downstream,” he said. Liquefaction capacity is roughly half regasification capacity: 454mn mt/yr compared with 947mn mt/yr.

“We see a gradual decline in new liquefaction capacity until the next wave of Canada, Mexico and Qatar from 2025 onwards. Demand in Japan is likely to stabilise or decrease, but should rise in China, India and southeast Asia where it can complement domestic production and replace coal and fuels in industry and power generation. In Latin America and Africa, LNG will complement renewable energy. LNG trade could grow at an average of 3-4%/year for the next 20 years, almost doubling in volume from today.

“South Korea and Japan already have far more regasification capacity than their annual demand requires. China is building more regasification and it gives them the opportunity to arbitrage between pipeline and LNG imports and to cope with demand seasonality,” he says.

Prices were also volatile: from the very low demand in the summer and attempts by buyers to invoke force majeure, the market picked up in the autumn. This surprised many participants who had thought the market was oversupplied. But opportunistic buyers snapped up cheap cargoes. And in some cases pipeline gas was turned down to make room for LNG.

For some buyers, LNG is an alternative to pipeline gas: it drives a wedge between a monopolist supplier and its market, improving the buyer’s negotiating position. This is the case in Lithuania and Croatia for example. For others, it is a choice between LNG or other fossil fuels such as diesel or coal.

These latter countries are more vulnerable to upstream risk: “LNG is still a physical commodity. One of the reasons for the high prices in late 2020 was congestion in the Panama Canal, coinciding with the cold weather and with a tight shipping market,” Demoury says.

These latter countries are more vulnerable to upstream risk: “LNG is still a physical commodity. One of the reasons for the high prices in late 2020 was congestion in the Panama Canal, coinciding with the cold weather and with a tight shipping market,” Demoury says.

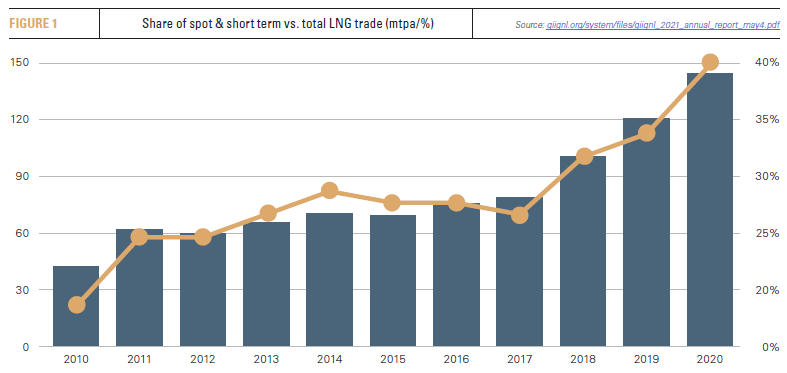

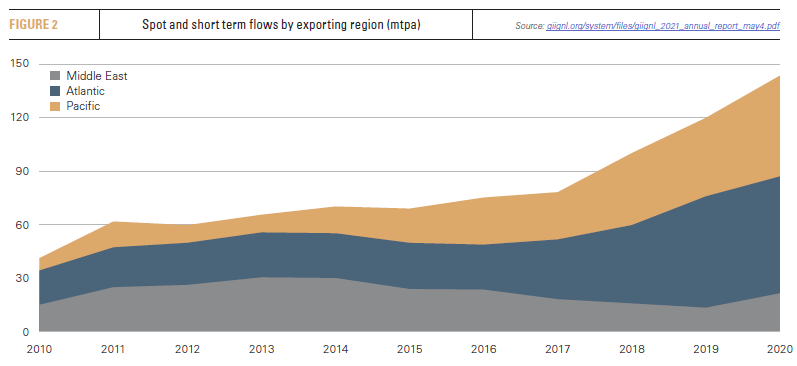

One of the most conspicuous changes was the shift from long-term to short and spot trade. 23.5mn mt more LNG were delivered within three months from the transaction date in 2020 than in 2019, reaching 35% of total imports during the year or 125mn mt, compared with 27% of total imports in 2019. Overall trade in LNG however grew just 1.4mn mt.

Most of that growth in spot trade may be explained by countries with a high sensitivity to price, such as India; or countries with the ability to arbitrage between pipeline gas and spot LNG, such as China or Turkey, he said. China saw annual growth of 12%, still impressive when compared with 14% the year before.

“Japan also took more spot cargoes as it nominated less from its long-term contracts and took advantage of the market to manage demand uncertainty. Portfolio players also moved cargoes around within their sales, buying cheap spot cargoes to honour long-term contracts,” Demoury says.

LNG portfolio players with a bigger downstream position may also have the option to deliver not gas to a terminal, but MWh at the customer’s power grid. That could free a cargo up for a more profitable sale elsewhere.

But there are limits to the extent that short-term cargoes can grow their share of the overall market: security of supply downstream and necessary return on investments upstream remain important and that implies a continuing need for term contracts. “We don’t see short term supply growth continuing at the same rapid pace for the next few years, now that the build-up of the first wave of US capacity is complete,” he says.

Another feature of last year was that the market was balanced mainly by producers shutting in production, he said. As well as the US, Egypt responded to price signals by curtailing its exports. And Algeria, normally a major LNG exporter, used gas to meet domestic demand instead.

But there were other, more familiar factors at play too that limited the supply: “Trinidad & Tobago and Malaysia each sold 2.4mn mt less because of a feed gas shortage. Two other plants, Hammerfest LNG and Prelude, were stopped by a fire and by electrical problems respectively. Another Australian project, Gorgon, also had technical problems with heat exchangers,” he says.

Shipping

A major element of the delivered cost of LNG is the freight and Demoury believes “there are still inefficiencies to be squeezed out of shipping. Last year the rising share of LNG freight in the total LNG cargo cost, in addition to increased charter rates volatility, drove more companies to look at hedging the cost of freight. Some financial instruments have been developed for hedging purposes. The NYMEX LNG Freight Futures or the Spark joint venture owned by Kpler and Powernext are examples.

“Last year Singapore was the major re-exporting country, followed by France. Traders increasingly recognise the value of LNG storage – including in some cases vessels used as floating storage – for trading opportunities,”

Emissions

GIIGNL is working both on its own and with other organisations to combat emissions, which are still perceived in some quarters as a problem facing LNG.

“There is no uniform methodology that is specific to LNG for the time being. More transparent and verifiable data should be disclosed,” Demoury explains. “GIIGNL has begun work on a common approach to monitoring, reporting and verifying emissions which it will publish in October. It has appointed a team of 30 experts from 19 companies within its membership to work on it.

“There is no uniform methodology that is specific to LNG for the time being. More transparent and verifiable data should be disclosed,” Demoury explains. “GIIGNL has begun work on a common approach to monitoring, reporting and verifying emissions which it will publish in October. It has appointed a team of 30 experts from 19 companies within its membership to work on it.

“The aim is to quantify the carbon footprint associated with each cargo and reduce it as much as possible. The footprint varies from site to site: facilities in Qatar, Russia and the US will all have different footprints. And the methodology to quantify the emission intensity of associated gas will be different from the methodology used for dry gas, for example. Emissions which cannot be avoided or reduced could be offset through the purchase of carbon credits.

“Transparency will become more important as LNG customers and the financial sector focus more on environment, society and governance. Policy-makers will also demand more information on the carbon intensity of LNG, such as the Methane Strategy in the EU,” he says.

Unsurprisingly, Demoury does not understand the World Bank’s negative position on LNG [see previous feature]. It has advised governments not to support LNG as a bunkering fuel as it believes it would only play a minor role compared with hydrogen or ammonia.

This is “clearly wrong,” he says. “Hydrogen and ammonia are still over a decade away as a bunkering fuel in meaningful volumes. LNG is a fuel that is already technically and commercially ready to help with the transition. It is reducing emissions now as it can also be a starting point towards net zero emissions, through offsets, fuel cells, bio and synthetic LNG or blending with hydrogen.

“It is cheaper than heavy fuel oil on an energy content basis and the payback time for conversions is short. LNG as a marine fuel will be needed for the next International Maritime Organisation’s objective to reduce shipping emissions by 40% by 2030 compared with 2008.”

But the World Bank’s pleas appear to have fallen on deaf ears – in some quarters, at least. As a FueLNG vessel refuelled an Aframax crude tanker in Singapore with LNG early in May, Keppel, Anglo-Dutch major Shell’s partner in the bunkering joint venture, praised the good that LNG can do today.

“LNG is an immediately available fuel solution that can reduce the environmental impact of maritime transport. The use of LNG as a marine fuel reduces greenhouse gas emissions by up to 23% on a well-to-wake basis, compared with current oil-based marine fuels,” the company said.

The event was attended by the Singapore Maritime & Ports Authority CEO Quah Ley Hoon, who said the event was "another milestone in Singapore’s journey as an LNG bunkering hub.”