Is FLNG Just a Niche Supply Source?

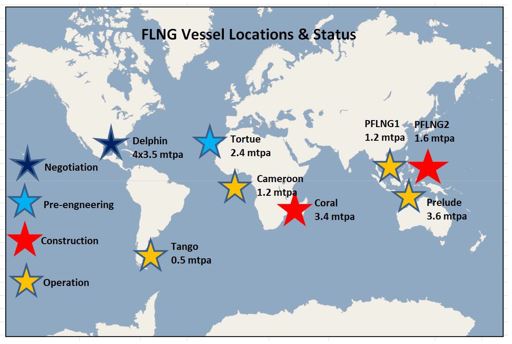

In addition to the five units mentioned above, one more is in construction (Coral), one in pre-engineering (Tortue), and one at an advanced stage of negotiation (Delfin). It has just been announced that the preliminary engineering for the Tortue project has been awarded to KBR, and Golar LNG has been chosen to provide the FLNG vessel, which will be based on a converted tanker, Gimi, similar to the Cameroon vessel. The Coral FLNG is currently under construction in Korea and is due for delivery in 2022.

This rate of progress appears slow. But the LNG industry is by tradition relatively cautious, and the application of new technology has to be carefully assessed to ensure that it will deliver both technically and commercially. A recent review by the author of industry attitudes to FLNG risk found a range from cautious optimism to rejection. This is quite different from the attitude expressed about the ‘sister’ technology of floating storage and regasification units, which is regarded as well proven and acceptable although still relatively new (the first unit started up only 25 years ago). But liquefaction is a far more complex process.

|

Advertisement: The National Gas Company of Trinidad and Tobago Limited (NGC) NGC’s HSSE strategy is reflective and supportive of the organisational vision to become a leader in the global energy business. |

FLNG vessel locations and status

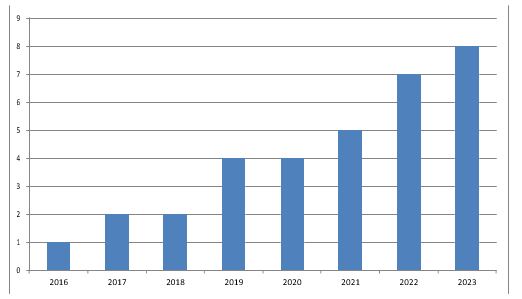

Aggregate number of FLNG vessels by start-up year

This article explores key factors that are likely to affect the scope of FLNG’s role in LNG production.

Physical capacity limitations

Placing a liquefaction plant on an LNG tanker limits the plant’s size and production capacity. The Prelude vessel is the largest offshore floating structure in the world at 488 metres long and 74 metres wide and displaces 600,000 tons—five times that of a world-class aircraft carrier! Yet it only produces 3.6 million tonnes per annum (mtpa)—just less than an industry-standard onshore train of 4 mtpa. Golar LNG’s vessels are based on converted Moss-type tankers with the liquefaction facilities placed on sponsons, giving overall dimensions of approximately 300 metres long and 60 metres wide—still physically very large—and producing 2.4 mtpa. Compare this to the recent Sabine Pass onshore plant, which has 6 trains producing some 27 mtpa. To match this production would require 7 Preludes or 11 Golar vessels.

On-stream time

A major weakness of FLNG is the unpredictable availability of the offloading system due to the dependence on sea conditions of both the berthing of the offtake tanker and the connection of loading arms. This is of particular concern in open-ocean conditions and less so at inshore locations, for example Cameroon. The preliminary arrangements for the Tortue development appear to include an extensive offshore breakwater which is apparently intended to address this issue.

Weather-related delays in offloading could limit FLNG’s potential to become a world-scale source of LNG and position it as better aligned to a spot market or niche supply role. However, this risk could be mitigated by operators if they were able to offer a backup supply to meet the contracted production.

Attitude to risk

As mentioned earlier, the industry is still generally very cautious about the risk of this new technology. The general view has been that ‘we may do it if we have to, but we would rather invest in an onshore project.’ This attitude is likely to change as confidence builds with more FLNG units coming on stream, but will limit current expansion, particularly if a developer has onshore or nearshore gas fields available for development. Shell often referred to the Prelude as a technology development project intended to identify challenges and test solutions to them. On the other hand, the approach by Golar LNG seems to be quite different, in that it is offering a commercial solution based on proven components and risk aversion does not appear to be significant. Having said that, it should be noted their current projects are in less challenging environments—Cameroon inshore and Tortue inside a breakwater. So this is not a true like-with-like comparison.

Offshore gas reserves

A significant factor in determining if FLNG will be niche or world-scale will be the number and size of future offshore gas fields available for development compared to those onshore. Recent finds in East Africa indicate there is a lot of gas offshore Mozambique and Tanzania; but the main developers, ExxonMobil and Anadarko, favour an onshore solution. However, Eni have favoured a first-phase FLNG solution, which is currently under construction (Coral FLNG). A recent report stated that

80 per cent of the world’s gas reserves were located in 10 countries, with Iran, Qatar, and Russia by far the largest. These locations are predominately onshore or nearshore, and thus likely to be processed by onshore plants. For major LNG production, the offshore fields need to be remote, and these appear to be less prevalent than onshore or nearshore fields. This suggests that FLNG is likely to remain more of a niche source.

Costs

It is too early to get an accurate view of FLNG costs. The current capital cost estimate ranges widely, from $3,000/tpa (tonne per annum) capacity for Prelude to $600/tpa for Golar LNG. But the price of the unit is only part of the cost. For example, at Tortue, considerable additional capital cost will be added by the construction of an offshore breakwater and related infrastructure.

The most significant cost disadvantage of FLNG is the cost of operations, which is significantly higher offshore due to the remoteness and the need to transport personnel and equipment by helicopter or supply boat and possibly even mobilize floating cranes or hotels. Offshore operations are inherently more expensive than onshore, particularly if the onshore plant is located in an established industrial area.

Marginal fields enabling technology

Drawing a parallel with early offshore oil production’s use of floating production storage and offloading (FPSO) vessels, FLNG can be regarded as a technology that makes it possible to estimate the longer-term performance of a particular reservoir before making a final investment decision on the major production scheme. This argument would tend to favour FLNG being considered more as a marginal field enabling tool than for longer-term world-scale LNG production. FLNG’s flexibility as a reusable asset lends itself to this application.

Reusable asset

One of the major advantages of FLNG has been argued to be the ability to relocate a plant to a new field (originally envisaged as an end-of-field-life solution). This has already been demonstrated twice, with the Caribbean FLNG (Tango) unit relocated from Columbia to Argentina and Petronas Satu relocated from Sarawak to Sabah. Had these facilities been developed as onshore plants, they would have been expensive sunk costs. In hindsight it is interesting to note that had the Egyptian liquefaction plants at Idku and Damietta been developed as floating units, they could have been relocated during the six-year period during which no gas was available. A recent article stated the compensation for nonproduction at Damietta was around $2 billion. Thankfully gas supplies have now become available.

Local content

One issue with the use of FLNG is the lack of local labour and materials. The facilities are normally fabricated in East Asian shipyards and installed offshore using international marine equipment, which standardizes the construction process and reduces costs. However, this leaves very little opportunity for local content on projects that have high in-country visibility. This could be a deciding factor in the choice between onshore and offshore processing. For example, in Mozambique, onshore has been favoured for the main development by ExxonMobil and Anadarko, and it is understood that local content has been an important part of that decision. Eni has decided to go the FLNG route with the Coral facility, but this has been reported as a method to get early production and revenue, perhaps implying that longer-term production could occur onshore.

Conclusions

Based on the factors discussed above, FLNG appears likely to remain a niche supplier. The physical size requirement would necessitate 7 Preludes or 11 Golar LNG units to match the production of a single unit such as Sabine Pass. This alone makes it difficult to see FLNG becoming a significant proportion of world-scale LNG production. The weather restrictions for berthing and loading, higher operating costs, lack of potential for incorporating local content, and onshore or nearshore location of most current undeveloped gas reserves make it even more likely that FLNG will be a niche supplier.

That said, it is interesting to note that oil FPSOs also began as niche players, employed as early production systems and facing major challenges to their acceptance for use in the Gulf of Mexico. Today there are 180 units worldwide, and they represent a significant share of the world’s crude oil production.

So perhaps the role of FLNG in world-scale LNG production will turn out to be more significant than projected in this article as more units are brought on stream, confidence in the technology increases, and costs are reduced. Time will tell.

The statements, opinions and data contained in the content published in Global Gas Perspectives are solely those of the individual authors and contributors and not of the publisher and the editor(s) of Natural Gas World.